On February 11, 1979, the Iranian state collapsed—not gradually, not through constitutional maneuvering, but in a sudden, cascading failure that left one of the Middle East’s most powerful monarchies dissolved almost overnight. That day, revolutionary forces seized key military installations in Tehran, senior officers declared neutrality, and the 2,500-year-old tradition of monarchy in Persia came to an abrupt end. In its place arose something unprecedented in modern geopolitics: an Islamic theocracy claiming divine authority over a modern nation-state.

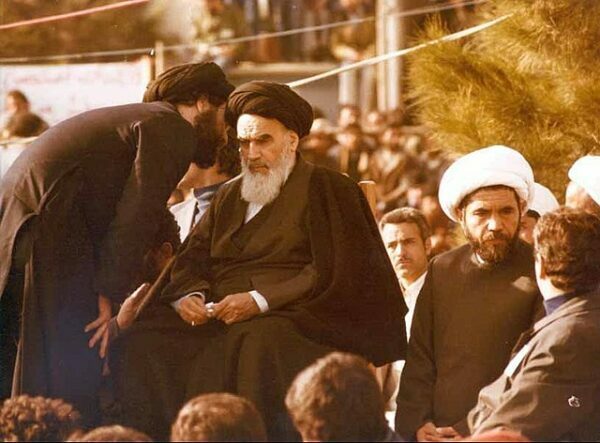

The event that would come to be known as the Iranian Revolution did not begin as an explicitly theocratic uprising. What made it distinctive—and ultimately decisive—was the way disparate grievances converged under a single clerical figure, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who fused revolutionary fervor with Shiite theology and redirected popular anger into a total rejection of secular authority.

For decades, Iran had been ruled by Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a Western-backed monarch who promised modernization, economic growth, and national prestige. The shah delivered rapid industrialization and sweeping social change, but at a steep cost. Political opposition was crushed by the secret police, wealth concentrated in elite circles, and traditional institutions—especially the clergy—were sidelined or openly antagonized. To many Iranians, the regime appeared not merely authoritarian, but culturally alien, propped up by foreign powers and indifferent to religious and social norms.

By the late 1970s, the fault lines widened. Inflation surged, unemployment rose, and corruption scandals eroded the regime’s legitimacy. Protests began among students and intellectuals, then spread to bazaars, mosques, and factories. What distinguished these demonstrations was their scale and persistence. Each crackdown produced larger funerals, each funeral became a new protest, and the cycle accelerated beyond the state’s ability to contain it.

Khomeini, exiled for years in Iraq and later France, emerged as the symbolic center of resistance. His sermons, smuggled into Iran on cassette tapes, framed the struggle not as a reform movement but as a moral and religious reckoning. The shah, he argued, was illegitimate not merely because he ruled harshly, but because sovereignty itself belonged to God. This claim—radical in its implications—would become the foundation of Iran’s new political order.

When the shah fled the country in January 1979, the regime’s fate was sealed. Khomeini returned to Tehran to a rapturous welcome, greeted by millions lining the streets. Yet power was still contested. A provisional government attempted to maintain order and preserve elements of the existing state, while revolutionary committees, clerical networks, and armed militias asserted control from below.

February 11 marked the decisive break. Military units defected en masse, revolutionary forces overran barracks and police stations, and the remnants of the imperial government collapsed. That night, Tehran radio announced the victory of the revolution. The monarchy was finished.

What followed was not a pluralistic republic, as some early supporters had hoped, but a systematic consolidation of clerical power. Within months, Khomeini sidelined secular allies, purged rivals, and pushed through a new constitution enshrining velayat-e faqih—the guardianship of the Islamic jurist. Under this doctrine, ultimate authority rested not with voters or parliament, but with a supreme religious leader tasked with safeguarding Islam itself.

The consequences reverberated far beyond Iran. The revolution overturned the strategic balance of the Middle East, shattered assumptions about modernization and secularization, and introduced a new model of political Islam that would inspire movements from Lebanon to Pakistan. Relations with the United States collapsed entirely later that year during the embassy hostage crisis, locking Iran into decades of isolation and confrontation.