On February 13, 1920, in a Kansas City YMCA, a group of Black baseball owners gathered under the leadership of Andrew “Rube” Foster and did something quietly revolutionary: they founded the Negro National League, the first successful, organized professional baseball league for African American players.

The decision was not merely about sport. It was about sovereignty.

For decades, Black players had been excluded from Major League Baseball by an unwritten but rigidly enforced color line. By the early twentieth century, segregated “barnstorming” teams crisscrossed the country, drawing large crowds but operating without financial stability or consistent schedules. Talent was abundant. Structure was not. What Foster recognized—more clearly than anyone—was that independence required institutions.

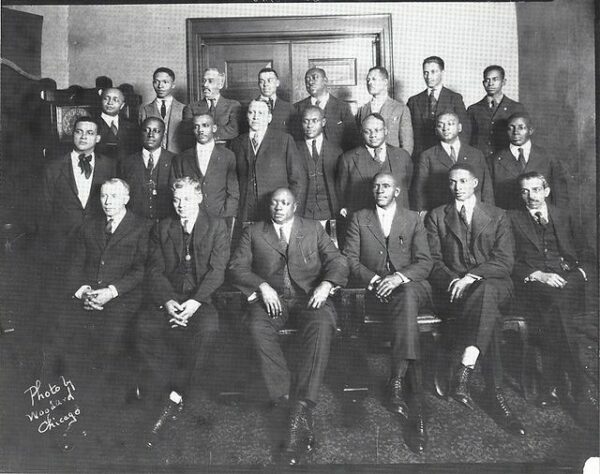

Foster, owner and manager of the Chicago American Giants, convened representatives from eight Midwestern teams: Chicago, Kansas City, St. Louis, Detroit, Indianapolis, Dayton, and Cuban Stars. The result was the Negro National League (NNL), a formally organized circuit with standardized contracts, schedules, and governance. It was, in essence, a declaration that Black baseball would not wait for admission into white institutions; it would build its own.

The founding of the league must be situated within its historical context. The year 1920 stood at the edge of the Great Migration, as millions of African Americans relocated from the rural South to industrial cities in the North and Midwest. Urban Black communities were growing rapidly. So too were Black-owned businesses, newspapers, churches, and civic organizations. The NNL emerged as part of this broader architecture of self-determination.

The league’s early years demonstrated both its fragility and its brilliance. Travel was arduous. Financial backing was uneven. Ballparks were often rented from white teams. Yet the quality of play was extraordinary. Pitchers like Bullet Rogan, hitters like Oscar Charleston, and two-way stars who could dominate on mound and at bat drew enthusiastic crowds. Games were social events, accompanied by brass bands and community gatherings. Baseball was not simply recreation; it was affirmation.

Rube Foster’s genius lay not only in organizing the league but in understanding its moral dimension. He insisted on discipline, professionalism, and economic cooperation among team owners. The league’s constitution included revenue-sharing mechanisms and dispute-resolution procedures—measures designed to protect Black capital from internal collapse. Foster knew that white skepticism would be relentless. The league had to succeed on its own terms.

The NNL’s formation also signaled something larger about American modernity. Segregation, while oppressive, inadvertently fostered parallel institutions—schools, banks, newspapers, and now a baseball league—that became incubators of leadership and excellence. The Negro National League was part of that ecosystem. It cultivated not only athletes but entrepreneurs and civic leaders.

Over time, additional Negro leagues formed, including an Eastern Colored League and later iterations of the Negro National League itself. The original NNL operated until 1931, undone in part by the Great Depression. But its legacy endured. It created a professional platform that would later showcase legends such as Satchel Paige and, ultimately, Jackie Robinson—whose 1947 debut in Major League Baseball marked the formal end of the color barrier that had made the Negro leagues necessary.

Yet it would be a mistake to view the NNL merely as a prelude to integration. For more than two decades, it was a thriving cultural institution in its own right. It offered Black fans the chance to witness excellence unmediated by humiliation. It proved that organizational competence and commercial success did not depend on white approval.

In 2020, Major League Baseball formally recognized the Negro leagues as major leagues, incorporating their statistics into the official historical record. The gesture, long overdue, acknowledged what players and communities had always known: the level of competition had been elite.