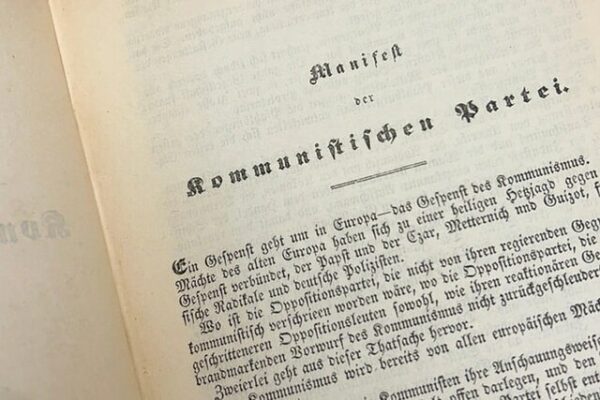

On February 21, 1848, a slim political pamphlet appeared in London that would reverberate across continents and centuries. Titled The Communist Manifesto, it was authored by two German intellectuals in exile—Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels—and commissioned by a small revolutionary organization known as the Communist League. Few at the time could have predicted that this brief tract, written in urgent and forceful prose, would become one of the most influential political documents in modern history.

Europe in early 1848 stood on the brink of upheaval. Industrialization had transformed cities and labor markets, creating vast wealth alongside grinding poverty. Political systems remained largely monarchical and aristocratic, even as new middle classes and urban workers demanded representation. In this climate of tension, Marx and Engels sought to provide not merely commentary, but a theory of history—and a call to action.

The pamphlet opens with one of the most famous lines in political literature: “A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism.” From the outset, the authors frame communism not as a marginal doctrine, but as a rising force already feared by Europe’s established powers. The Manifesto argues that history itself is driven by class struggle. From ancient slave societies to feudalism and into the modern industrial age, human societies, they contend, have been defined by conflict between oppressor and oppressed.

In the nineteenth century, according to Marx and Engels, that struggle had taken a new form: the bourgeoisie versus the proletariat. The bourgeoisie—owners of factories, capital, and industry—had revolutionized production and shattered feudal constraints. Yet in doing so, they had created their own antagonist: the working class, or proletariat, whose labor powered industrial society but who owned none of its means of production.

Marx and Engels praised the bourgeoisie for its dynamism, describing how capitalism had unleashed technological innovation and global trade. But they argued that capitalism was inherently unstable. Economic crises, they claimed, were built into the system, as overproduction collided with limited consumer purchasing power. Workers, paid only subsistence wages, could not buy back the goods they produced, leading to periodic collapses.

The solution they proposed was radical: the abolition of private ownership of the means of production. In its place, they envisioned collective ownership, the dissolution of class distinctions, and ultimately the withering away of the state itself. Contrary to critics who accused communists of seeking to abolish personal property altogether, the Manifesto distinguished between personal possessions and industrial capital. The target, they argued, was not individual belongings but the system that allowed one class to extract profit from another’s labor.

The text concludes with a direct appeal to workers across national boundaries. “Workers of the world, unite!” became its enduring slogan—an appeal that transcended borders at a time when nationalism was itself gaining strength. The authors believed that the proletariat, once conscious of its shared interests, would overthrow capitalist structures and inaugurate a classless society.

Ironically, the Manifesto was published just as Europe erupted into revolution. Within days, uprisings broke out in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, and elsewhere. Though most of these revolutions ultimately failed or were suppressed, they marked a turning point in European political life. Marx himself was expelled from multiple countries before settling in London, where he would continue his work, later producing Das Kapital.

At the time of its publication, The Communist Manifesto had a modest circulation. It was printed in German and distributed among émigré radicals. Only later, as socialist and labor movements grew in the late nineteenth century, did the text achieve global prominence. By the twentieth century, its ideas would shape revolutions in Russia, China, and beyond—often interpreted in ways Marx himself might not have anticipated.

Whether praised as a visionary critique of industrial capitalism or condemned as the intellectual seedbed of totalitarian regimes, the document’s historical significance is undeniable. On February 21, 1848, Marx and Engels distilled a sweeping theory of economics, politics, and human history into a pamphlet scarcely fifty pages long—yet one that would help define the ideological struggles of the modern age.