On September 4, 1957, nine students tried to attend their new school for the first time and participated in one of the significant events of the Civil Rights Movement. Governor Orval Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to surround Central High School in Little Rock, preventing the nine African American students, known as the Little Rock Nine, from entering the school.

“In 1954 the United States Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were illegal. The case, Brown v. The Board of Education, has become iconic for Americans because it marked the formal beginning of the end of segregation.

But the gears of change grind slowly. It wasn’t until September 1957 when nine teens would become symbols, much like the landmark decision we know as Brown v. The Board of Education, of all that was in store for our nation in the years to come.

The “Little Rock Nine,” as the nine teens came to be known, were to be the first African American students to enter Little Rock’s Central High School. Three years earlier, following the Supreme Court ruling, the Little Rock school board pledged to voluntarily desegregate its schools. This idea was explosive for the community and, like much of the South, it was fraught with anger and bitterness,” explains The National Museum of African American History and Culture.

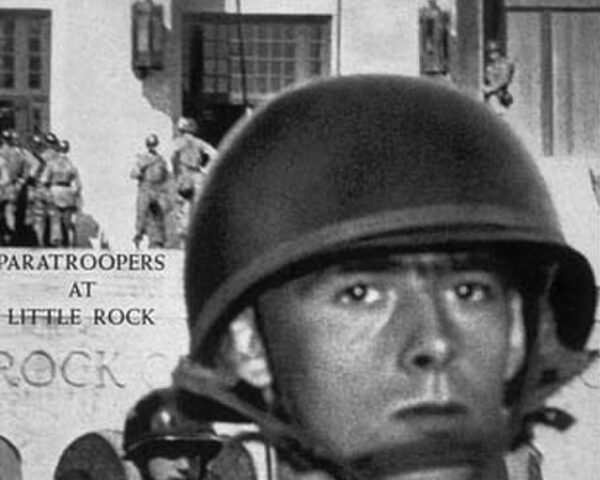

Faubus’s decision to use the Arkansas National Guard to block the students’ entry was a significant act of defiance against federal authority and the integration of public schools. This event drew national attention and marked a critical turning point in the struggle for civil rights in the United States. It ultimately led to President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s intervention, as he federalized the Arkansas National Guard and dispatched the 101st Airborne Division to ensure the Little Rock Nine could safely enter Central High School.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Governor Faubus, and Little Rock Mayor Woodrow Mann “discussed the situation over the course of 18 days, during which time the nine students stayed home. The students returned to the high school on September 23, entering through a side door to avoid the protesters’ attention and wrath.

They were eventually discovered, however, and white protesters became violent, attacking African American bystanders as well as reporters for northern newspapers. The students were sent home, but they returned on September 25, protected by U.S. soldiers. Despite Eisenhower’s publicly stated reluctance to use federal troops to enforce desegregation, he recognized the potential for violence and state insubordination. He thus sent the elite 101st Airborne Division, called the “Screaming Eagles,” to Little Rock and placed the Arkansas National Guard under federal command,” according to Brittanica.

“The Little Rock Nine continued to face physical and verbal attacks from white students throughout their studies at Central High. One of the students, Minnijean Brown, fought back and was expelled. The remaining eight students, however, attended the school for the rest of the academic year. At the end of the year, in 1958, senior Ernest Green became the first African American to graduate from Little Rock Central High School.”

Governor Faubus went on to win reelection in 1958, and, rather than permit desegregation, closed all of Little Rock’s schools. They did not open until 1960

The members of the Little Rock Nine faced immense challenges, including physical and verbal abuse, as they worked to integrate Central High School. Despite these difficulties, they went on to achieve success in various fields and played crucial roles in the broader civil rights movement, demonstrating the resilience and determination of individuals in the face of racial discrimination and segregation.