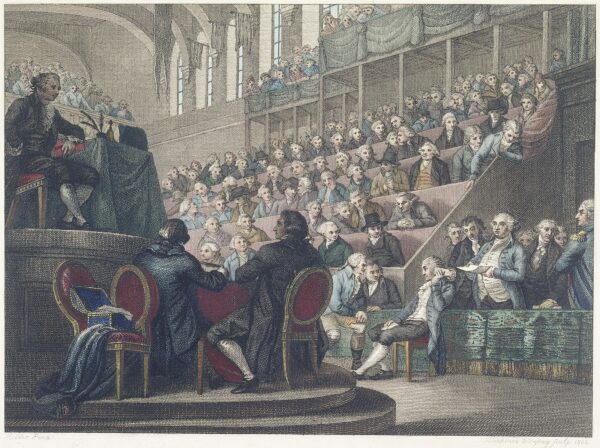

The trial of Louis XVI was a pivotal event during the French Revolution that unfolded in the late 18th century. The revolution, marked by a fervent desire for political and social change, reached a critical juncture when the National Convention, the revolutionary assembly, put the former king on trial. The trial began on December 11, 1792, and marked a historic moment as it symbolized the shift from a constitutional monarchy to a republic.

Louis XVI faced a range of charges, including conspiracy against the state, collusion with foreign powers, and attempts to flee the country. The trial was a significant departure from traditional legal proceedings, as it was both a political and ideological trial. The Montagnards, a radical faction within the Convention, led the prosecution, arguing that the king’s actions had jeopardized the gains of the revolution and threatened the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Louis’ team immediately went to work preparing his defense. His lead counsel was Lamoignon de Malesherbes, a 71-year-old statesman who had twice served as royal minister; when asked what had compelled him to fight this losing battle, Malesherbes replied, “I was called twice to the service of him who was my Master, when all the world coveted that honor; and I owe him the same service now when it has become one which many reckon dangerous” (Carlyle, 545). Louis’ other defenders included another senior jurist, François-Denis Tronchet, as well as the younger and more eloquent Romain Desèze,” writes The World History Encyclopedia.

Louis retained the final say over his legal arguments and approved all his counselors’ speeches. He refused to allow them to claim that he was ignorant of the law, nor would he follow the example of Charles I and deny the authority of the Convention. Instead, he would refer to the Constitution of 1791, which held France’s monarch as inviolable, thus making a trial illegal. Although Louis had told Malesherbes that he believed their case was winnable, it appeared that he had secretly come to accept his situation, as he spent Christmas Day revising his last will and testament. In it, he wrote to his son that should he ever have the misfortune of becoming king, he should not seek revenge for his father’s death but should seek only the happiness of his subjects. He wrote the queen asking for forgiveness for any grief he may have caused her during their marriage. In a final act of defiance, he signed the will “King Louis XVI of France and Navarre,” the title he had held under the Ancien Régime.

The trial of the King captured the intense ideological divisions within the revolutionary factions. The Girondins, more moderate revolutionaries, were initially hesitant about the regicide, while the radical Jacobins, especially figures like Maximilien Robespierre, advocated for the king’s execution. The trial culminated in a pivotal vote on January 15, 1793, when the National Convention declared Louis XVI guilty and sentenced him to death by guillotine. This marked a historic moment as it marked the first time in European history that a reigning monarch was tried and executed by his own people.

The execution of Louis XVI on January 21, 1793, had profound consequences both within France and across Europe. It intensified the radicalization of the revolution and led to increased political instability. Internationally, the execution of a monarch sent shockwaves, with many European monarchies expressing concern.