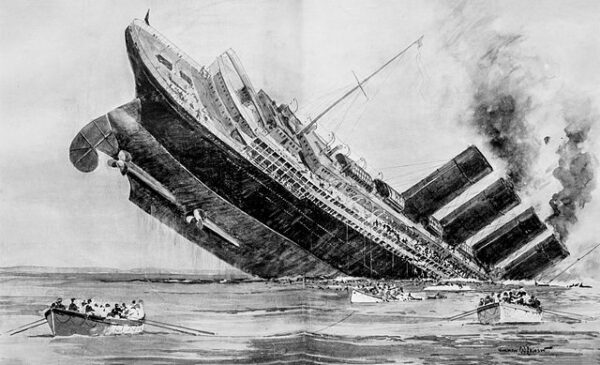

On May 1, 1915, the RMS Lusitania left port in New York to travel back to Great Britain. It never made it when it was sunk by German U-Boats nearly a week later, changing the course of World War 1.

“The Lusitania, which was owned by the Cunard Line, was built to compete for the highly lucrative transatlantic passenger trade. Construction began in 1904, and, after completion of the hull and main superstructure, the Lusitania was launched on June 7, 1906. The liner was completed the following year, at which time it was the largest ship in the world, measuring some 787 feet (240 metres) in length and weighing approximately 31,550 tons; it was surpassed the following year by its sister ship, the Mauretania. Although luxurious, the Lusitania was noted more for its speed. On September 7, 1907, the ship made its maiden voyage, sailing from Liverpool, England, to New York City. The following month it won the Blue Riband for fastest Atlantic crossing, averaging nearly 24 knots. The Mauretania would later claim the Blue Riband, and the two ships regularly vied for the honour,” writes Britannica.

“The sinkings of merchant ships off the south coast of Ireland and reports of submarine activity there prompted the British Admiralty to warn the Lusitania to avoid the area and to recommend adopting the evasive tactic of zigzagging, changing course every few minutes at irregular intervals to confuse any attempt by U-boats to plot her course for torpedoing. The ship’s captain, William Thomas Turner, chose to ignore these recommendations, and on the afternoon of May 7 the vessel was attacked. A torpedo struck and exploded amidships on the starboard side, and a heavier explosion followed, possibly caused by damage to the ship’s steam engines and pipes. Within 20 minutes the Lusitania had sunk, and 1,198 people were drowned. The loss of the liner and so many of its passengers, including 128 U.S. citizens, aroused a wave of indignation in the United States, and it was fully expected that a declaration of war would follow, but the U.S. government clung to its policy of neutrality.

The Lusitania was carrying a cargo of rifle ammunition and shells (together about 173 tons), and the Germans, who had circulated warnings that the ship would be sunk, felt themselves fully justified in attacking a vessel that was furthering the war aims of their enemy. The German government also felt that, in view of the vulnerability of U-boats while on the surface and the British announcement of intentions to arm merchant ships, prior warning of potential targets was impractical. On May 13, 1915, the U.S. government sent a note to Berlin expressing an indictment of the principles on which the submarine war was being fought. The note was written by Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, a pacifist who was leery of issuing too forceful a rebuke out of fear that it might draw the United States into the war.”

But pacifist sentiments could only last so long.

ThoughCo notes how things changed as Germany could not put the genie back in the bottle following the sinking of the Lusitania: “On January 31, 1917, Germany declared that it was placing an end to its self-imposed moratorium on unrestricted warfare in waters that were within the war zone. The United States government broke diplomatic relations with Germany three days later, and almost immediately a German U-boat sunk the Housatonic which was an American cargo ship.

On February 22, 1917, Congress enacted an arms appropriations bill that was designed to prepare the United States for war against Germany. Then, in March, four more U.S. merchant ships were sunk by Germany which prompted President Wilson to appear before Congress on April 2 requesting a declaration of war against Germany. The Senate voted to declare war against Germany on April 4, and on April 6, 1917, the House of Representatives endorsed the Senate’s declaration, causing the United States to enter World War I.”

The Lusitania left port and changed history on this day in 1915.