On June 7, 1494, two rival powers sat down to sign a treaty that would shape North and South America for the centuries that followed.

Following the reports of Christopher Columbus’s discoveries in the Americas, Spanish rulers Ferdinand and Isabella went to the Vatican to help back Spanish claims to the New World. They hoped to stop their seafaring neighbors to the South—Portugal—along with other European rivals.

The Spanish were right to worry. Over the previous decades, the Portuguese had begun to build its empire, first colonizing the uninhabited North Atlantic island groups of Madeira from 1420, the Azores from 1439, and Cape Verde from 1462.

According to historians, “when the treacherous Cape Bojador was navigated in 1434 by the explorer Gil Eannes, the Portuguese were able to access the trade and resources in West Africa without dealing with Islamic North African traders. The new king, John II of Portugal (r. 1481-1495), pushed for more and so São Tomé and Principe were colonized from 1486. However, yet another island group, the inhabited Canary Islands, were prized by both Spain and Portugal, and the colonial competition heated up considerably.”

To accommodate the European power couple, Brittanica writes, “the Spanish-born pope Alexander VI issued bulls setting up a line of demarcation from pole to pole 100 leagues (about 320 miles) west of the Cape Verde Islands see Cabo Verde. Spain was given exclusive rights to all newly discovered and undiscovered lands in the region west of the line. Portuguese expeditions were to keep to the east of the line. Neither power was to occupy any territory already in the hands of a Christian ruler.”

The New World Encyclopedia explains, “The Treaty of Tordesillas was intended to resolve the dispute between the rival kingdoms of Spain and Portugal to newly discovered, and yet-to-be discovered, lands in the Atlantic. A series of papal bulls, after 1452, had attempted to define these claims. In 1481, the papal Bull, Aeterni regis, had granted all land south of the Canary Islands to Portugal. These papal bulls were confirmed, with papal approval, by the Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo (1479–1480).

The bull did not mention Portugal or its lands, so Portugal could not claim newly discovered lands even if they were east of the line. Another bull, Dudum siquidem, entitled Extension of the Apostolic Grant and Donation of the Indies and dated September 25, 1493, gave all mainlands and islands then belonging to India to Spain, even if east of the line. The Portuguese King John II was not pleased with this arrangement, feeling that it gave him far too little land and prevented him from achieving his goal of possessing India. (By 1493, Portuguese explorers had only reached the east coast of Africa). He opened negotiations with King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain to move the line to the west and allow him to claim newly discovered lands east of the line. The treaty effectively countered the bulls of Alexander VI and was sanctioned by Pope Julius II in a new bull of 1506.

Very little of the newly divided area had actually been seen. Spain gained lands including most of the Americas. The easternmost part of current Brazil, when it was discovered in 1500 by Pedro Álvares Cabral, was granted to Portugal. The line was not strictly enforced—the Spanish did not resist the Portuguese expansion of Brazil across the meridian. The treaty was rendered meaningless between 1580 and 1640, while the Spanish King was also King of Portugal. It was superseded by the 1750 Treaty of Madrid, which granted Portugal control of the lands it occupied in South America. However, that treaty was immediately repudiated by Spain.

Despite their best efforts, the treaty did not slow the Portuguese down. “When in 1498 the explorer Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) sailed around the Cape of Good Hope and into the Indian Ocean, suddenly the Portuguese gained access to a whole new trade network involving Africans, Indians, and Arabs. Da Gama pushed on to India where Portugal established several colonies from where further colonizing expeditions sailed east to Indonesia and Japan,” noted the World History Encyclopedia.

“In 1519-22, the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480-1521), then in the service of Spain, sailed around the southern tip of South America and pioneered a maritime route across the Pacific Ocean and on to East Asia. The expedition eventually circumnavigated the globe, but it was access to the spice trade that was crucial. Now Spain became a rival to Portugal in this lucrative trade. The source of many spices was the Maluku Islands or the Moluccas in what is today Indonesia. Not for nothing were these islands simply called the Spice Islands. Spanish and Portuguese navigators and cartographers debated as to where exactly the islands were located on the map: in Portugal or Spain’s sphere of influence according to the Treaty of Tordesillas? There were even accusations that cartographers were deliberately misplacing islands on maps, either to keep their location secret or to support the idea that their country had a rightful claim over them. Magellan had believed the Spice Islands were in the Spanish sphere and had won royal backing for his expedition on those grounds. As it turned out, Magellan was wrong, but Portugal did pay Spain a large quantity of gold to maintain control of the islands. Another area of contention was the lower half of South America, particularly the River plate where both kingdoms laid a claim based on the inexactitude of the line of the demarcation of Tordesillas.

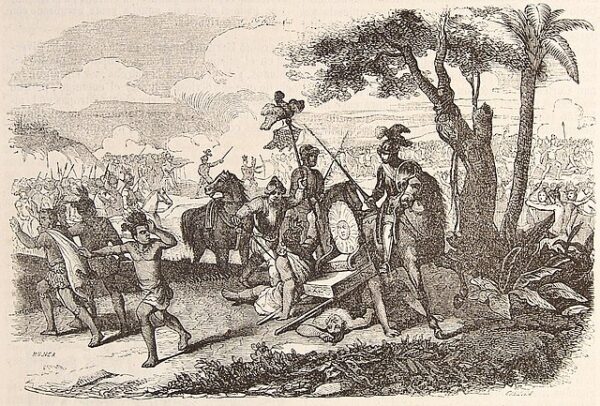

In 1521 Hernán Cortés led a force of conquistadores which attacked the Aztec Empire in Mexico and claimed it for Spain. In 1533 Francisco Pizarro led a force which attacked the Inca Empire in South America, bringing about its eventual collapse. Suddenly, the Spanish had control of two massive empires and all their riches. Meanwhile, in 1532, the Portuguese began to colonize Brazil, which fortunately for them, juts out from the continent in such a way as to cross the line set out by the Treaty of Tordesillas. Meanwhile, the 1529 treaty of Zaragoça (Saragosa) extended the dividing line of Tordesillas to the other side of the globe, confirming Portugal’s claim over the Spice Islands while Spain was given the Philippines (even if they were in Portugal’s sphere).”

The treaty, signed on June 7, 1494, played an important role in dividing Latin America and established Spain in the western Pacific. Nevertheless, The Treaty of Tordesillas soon became outdated in North America. Other European rulers simply ignored the papal bull and as decades passed, Spanish and Portuguese power began to decline and the two countries unable to hold onto many of their claims.

With the fall of Portuguese Malacca to the Dutch in 1511, the Dutch East India Company began controlling much of Indonesia, claiming Western New Guinea and Western Australia, as New Holland.

Eastern Australia remained in the Spanish half of the world until claimed for Britain by James Cook in 1770. But, even then, the Treaty still shaped borders. Ghil’ad Zuckerman, a historian of the period, noted, “the current border between Western Australia on the one hand, and South Australia and the Northern Territory on the other hand (originally the western border of New South Wales, 1788) is still based on the Tordesillas line.”