The impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson, the first such trial in American history, was a highly contentious and politically charged event that culminated in his acquittal on May 16, 1868. Johnson, who ascended to the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, quickly found himself at odds with the Radical Republicans in Congress. His lenient approach to Reconstruction and frequent clashes with Congress over the control of Reconstruction policies laid the groundwork for his impeachment.

The primary catalyst for Johnson’s impeachment was his violation of the Tenure of Office Act, a law passed by Congress in 1867 over Johnson’s veto. This act was designed to restrict the president’s power to remove certain officeholders without the Senate’s approval. Johnson tested this law by dismissing Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War and an ally of the Radical Republicans, and replacing him with Lorenzo Thomas. This bold move provided the House of Representatives with the ammunition it needed to initiate impeachment proceedings.

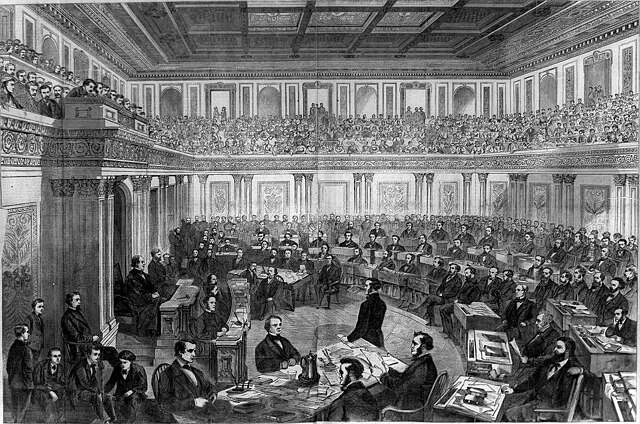

On February 24, 1868, the House voted to impeach Johnson, making him the first U.S. president to be impeached. The charges against him included eleven articles of impeachment, with the primary focus on his violation of the Tenure of Office Act. The impeachment process then moved to the Senate, where Johnson’s fate would be decided through a trial presided over by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase.

The trial began on March 5, 1868, and lasted for nearly three months. The prosecution, led by seven House managers, argued that Johnson’s removal of Stanton was illegal and part of a broader pattern of defying Congress and undermining its authority. They portrayed Johnson as a leader who was unfit to serve and whose actions threatened the stability of the nation during a critical period of Reconstruction.

Johnson’s defense team, composed of prominent attorneys such as William M. Evarts and Henry Stanbery, countered these arguments by asserting that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional and that Johnson had acted within his rights as president. They also contended that the impeachment was politically motivated and that removing Johnson from office would set a dangerous precedent.

As the trial progressed, it became clear that the outcome would hinge on a few key swing votes in the Senate. The Radicals needed a two-thirds majority, or 36 out of 54 senators, to convict and remove Johnson from office. The political climate was tense, with intense lobbying and political maneuvering on both sides.

On May 16, 1868, the Senate assembled to cast its votes on the eleventh article of impeachment, which was considered the most likely to secure a conviction. This article charged Johnson with attempting to undermine Congress by unlawfully removing Stanton and appointing Thomas. The moment was fraught with anticipation as each senator stood to cast his vote.

In the end, 35 senators voted to convict, while 19 voted to acquit. This fell one vote short of the required two-thirds majority. Among the key swing votes was that of Senator Edmund G. Ross of Kansas, whose decision to acquit was seen as crucial. Ross and several other Republicans who voted to acquit faced significant backlash from their party but argued that their decision was based on the principle of fair trial and the evidence presented.