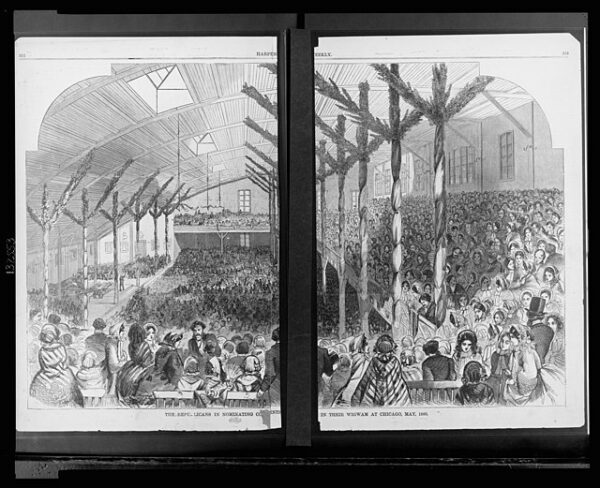

The Republican National Convention of 1860, held from May 16 to May 18 in the bustling city of Chicago, changed the course of American history and led the nation down the road to the Civil War. This convention, taking place in the specially constructed “Wigwam,” marked the emergence of Abraham Lincoln as a formidable political figure and set the stage for the dramatic and transformative 1860 presidential election.

Leading up to the convention, the Republican Party had only ever nominated one other person for president. By 1860, the party had gained significant momentum, drawing support from various northern constituencies opposed to the expansion of slavery into new territories and states. The party’s platform was explicitly anti-slavery, advocating for free soil and the containment of slavery to the southern states where it already existed.

The delegates arriving in Chicago were faced with the crucial task of selecting a candidate who could unite the party and appeal to a broad spectrum of voters in the North. Several prominent names were in contention for the nomination. The leading candidate was William H. Seward, a senator from New York and a staunch abolitionist with a national reputation. However, Seward’s outspoken views on slavery and his association with more radical elements of the party worried some delegates who feared he might be too polarizing to win the general election.

In contrast, Abraham Lincoln, a relatively lesser-known figure from Illinois, was emerging as a strong compromise candidate. Lincoln had made a name for himself through his debates with Stephen A. Douglas during the 1858 Illinois Senate race, which, despite his loss, had elevated his profile nationally. His moderate views on slavery, emphasizing containment rather than immediate abolition, positioned him as a unifying figure who could attract a broader base of support.

As the convention commenced, it became clear that Seward, while initially leading in the delegate count, could not secure the majority needed for the nomination. On the first ballot, Seward led with 173½ votes to Lincoln’s 102. However, Lincoln’s campaign team, led by David Davis and Leonard Swett, had worked tirelessly behind the scenes to sway undecided delegates and peel off support from other candidates. They emphasized Lincoln’s electability and his appeal to key swing states.

By the second ballot, Lincoln’s support surged to 181 votes, and on the third ballot, he clinched the nomination on May 18. The convention hall erupted in applause as Lincoln’s supporters celebrated his victory. Hannibal Hamlin of Maine was subsequently chosen as his running mate, balancing the ticket geographically and ideologically.

The Republican platform adopted at the convention was a clear articulation of the party’s principles. It called for the non-extension of slavery, support for a transcontinental railroad, and the implementation of a homestead law to encourage western settlement. The platform also endorsed protective tariffs and improvements in infrastructure, appealing to a broad coalition of northern industrialists, farmers, and working-class voters.

Lincoln’s nomination marked a significant shift in American politics. The Democratic Party, deeply divided over the issue of slavery, would split into Northern and Southern factions, each nominating their own candidate. This division ultimately played to Lincoln’s advantage in the general election, allowing him to win the presidency with a plurality of the popular vote and a decisive majority in the Electoral College.