On June 29, 1956, President Eisenhower signed a law that led to one of the greatest manmade wonders ever built: The United States Highway System. This act would become the biggest public works project in American history.

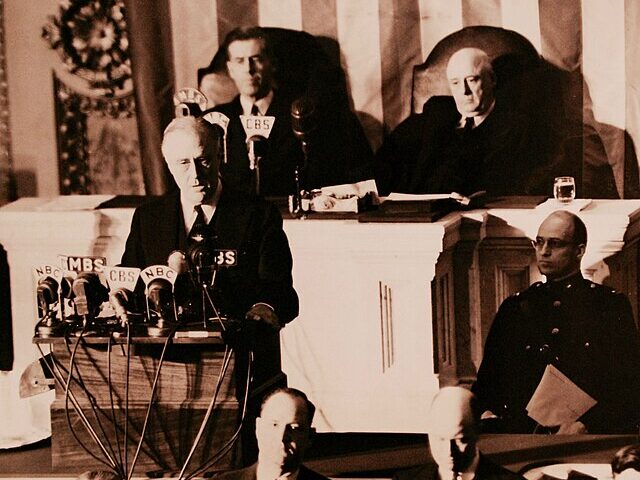

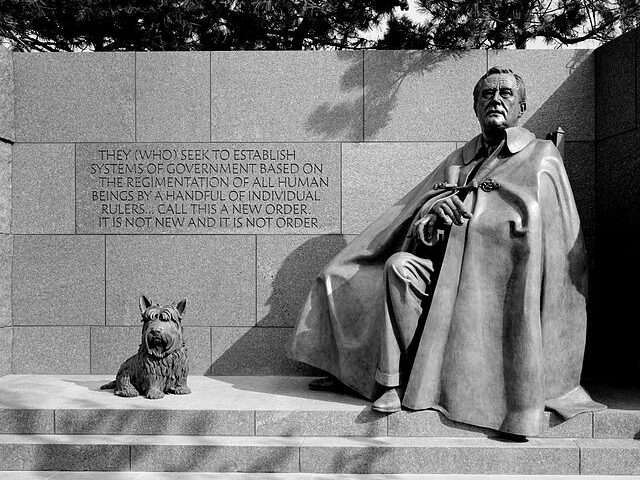

“By the late 1930s, writes The Department of Transportation, “the pressure for construction of transcontinental superhighways was building. It even reached the White House, where President Franklin D. Roosevelt repeatedly expressed interest in construction of a network of toll superhighways as a way of providing more jobs for people out of work.

He thought three east-west and three north south routes would be sufficient. Congress, too, decided to explore the concept. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1938 directed the chief of the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) to study the feasibility of a six route toll network. The resultant two-part report, Toll Roads and Free Roads, was based on the statewide highway planning surveys and analysis.

Part I of the report asserted that the amount of transcontinental traffic was insufficient to support a network of toll superhighways. Some routes could be self-supporting as toll roads, but most highways in a national toll network would not. Part II, “A Master Plan for Free Highway Development,” recommended a 43,000-kilometer (km) nontoll interregional highway network. The interregional highways would follow existing roads wherever possible (thereby preserving the investment in earlier stages of improvement). More than two lanes of traffic would be provided where traffic exceeds 2,000 vehicles per day, while access would be limited where entering vehicles would harm the freedom of movement of the main stream of traffic.

Within the large cities, the routes should be depressed or elevated, with the former preferable. Limited-access belt lines were needed for traffic wishing to bypass the city and to link radial expressways directed toward the center of the city. Inner belts surrounding the central business district would link the radial expressways while providing a way around the district for vehicles not destined for it. On April 27, 1939, Roosevelt transmitted the report to Congress.”

Although FDR urged Congress to take action, it would take the beginning of the Cold War and a decade and a half for a bill to reach the president’s desk.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower had first realized the value of a national system of roads after participating in the U.S. Army’s first transcontinental motor convoy in 1919; during World War II, he had admired Germany’s autobahn network. In January 1956, Eisenhower called in his State of the Union address (as he had in 1954) for a “modern, interstate highway system.” Later that month, Fallon introduced a revised version of his bill as the Federal Highway Act of 1956. It provided for a 65,000-km national system of interstate and defense highways to be built over 13 years, with the federal government paying for 90 percent, or $24.8 billion. To raise funds for the project, Congress would increase the gas tax from two to three cents per gallon and impose a series of other highway user tax changes. On June 26, 1956, the Senate approved the final version of the bill by a vote of 89 to 1; Senator Russell Long, who opposed the gas tax increase, cast the single “no” vote. That same day, the House approved the bill by a voice vote, and three days later, Eisenhower signed it into law,” notes The History Channel.

Highway construction began almost immediately, employing tens of thousands of workers and billions of tons of gravel and asphalt. The system fueled a surge in the interstate trucking industry, which soon pushed aside the railroads to gain the lion’s share of the domestic shipping market. Interstate highway construction also fostered the growth of roadside businesses such as restaurants (often fast-food chains), hotels and amusement parks. By the 1960s, an estimated one in seven Americans was employed directly or indirectly by the automobile industry, and America had become a nation of drivers.

Legislation has extended the Interstate Highway Revenue Act three times, and it is remembered by many historians as Eisenhower’s greatest domestic achievement.

The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 had several positive impacts on the United States that we still experience today. It improved national defense and still allows for the rapid movement of troops, equipment, and supplies across the country. It also enhanced highway safety by separating high-speed interstate traffic from local roads and providing standardized design and safety features and promoted commerce and economic growth by connecting the natoin together.

However, the act certainly has had its critics. The construction of the interstate highway system required the acquisition of vast amounts of land, including rich farmland, which often led to the displacement of communities and the destruction of neighborhoods. The system also contributed to urban sprawl, which led to the decline of city centers, increased dependence on automobiles, and sometimes even dislocated smaller towns that happened to be out of the orbit of large cities.

Still, the interstate highway system continues to be a vital component of the nation’s infrastructure and remains a wonder of the modern world.