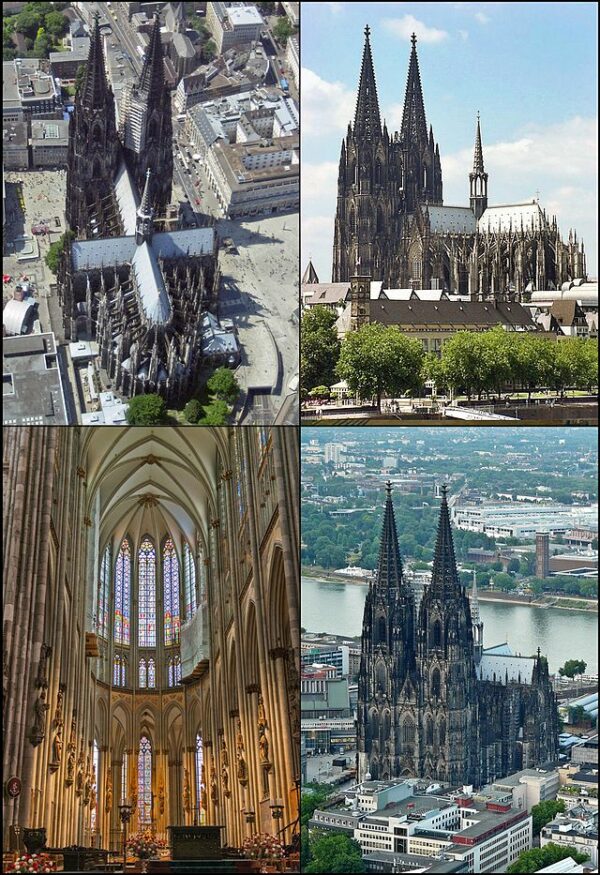

On August 14, 1880, builders placed the final touches on the Cologne Cathedral in Germany, completing a project that took over 630 years to finish. With the final stone laid, the cathedral became the tallest building in the world, a title it held until 1890 when a rival cathedral in Ulm took the top spot.

The completion of Cologne Cathedral served as a testament to the unwavering commitment of the people of Cologne and their deep connection to their city’s history and identity. Despite facing numerous challenges, including financial difficulties, changes in architectural styles, and even wars, the people continued to support the cathedral’s construction, passing down their dedication from one generation to the next.

Architects, craftsmen, and artisans played crucial roles in bringing the cathedral to its final form. The intricate details of the stained glass windows, the delicate sculptures, and the soaring spires were all the result of their skill and expertise. Every generation built upon the work of their predecessors, adding their unique touch to the building’s beautiful design and honored the original vision in 1248.

“Over seven centuries, its successive builders were inspired by the same faith and by a spirit of absolute fidelity to the original plans. Apart from its exceptional intrinsic value and the artistic masterpieces it contains, Cologne Cathedral bears witness to the strength and endurance of European Christianity. No other Cathedral is so perfectly conceived, so uniformly and uncompromisingly executed in all its parts.

Cologne Cathedral is a High Gothic five-aisled basilica (144.5 m long), with a projecting transept (86.25 m wide) and a tower façade (157.22 m high). The nave is 43.58 m high and the side-aisles 19.80 m. The western section, nave and transept begun in 1330, changes in style, but this is not perceptible in the overall building. The 19th century work follows the medieval forms and techniques faithfully, as can be seen by comparing it with the original medieval plan on parchment.

The original liturgical appointments of the choir are still extant to a considerable degree. These include the high altar with an enormous monolithic slab of black limestone, believed to be the largest in any Christian church, the carved oak choir stalls (1308-11), the painted choir screens (1332-40), the fourteen statues on the pillars in the choir (c. 1300), and the great cycle of stained-glass windows, the largest existent cycle of early 14th century windows in Europe. There is also an outstanding series of tombs of twelve archbishops between 976 and 1612,” writes UNESCO in its explanation for making the Cathedral a World Heritage Site.

“Of the many works of art in the Cathedral, special mention should be made to the Gero Crucifix of the late 10th century, in the Chapel of the Holy Cross, which was transferred from the pre-Romanesque predecessor of the present Cathedral, and the Shrine of the Magi (1180-1225), in the choir, which is the largest reliquary shrine in Europe. Other artistic masterpieces are the altarpiece of St. Clare (c. 1350-1400) in the north aisle, brought here in 1811 from the destroyed cloister church of the Franciscan nuns, the altarpiece of the City Patrons by Stephan Lochner (c. 1445) in the Chapel of Our Lady, and the altarpiece of St. Agilolphus (c. 1520) in the south transept.”

Although Cologne Cathedral was hit by several heavy bombs during World War II, notes the citiy, “it miraculously remained standing. However, it took many years to fully restore the building. In addition to the wounds from World War II, the damage caused by the weather and by pollution has to be repaired. As a result, Cologne Cathedral is a ‘permanent construction site.’”