The assassination of Pompey, one of the most prominent figures of ancient Rome, marked a pivotal moment in the political turmoil that engulfed the late Roman Republic. It occurred on September 28, 48 BC, on the orders of King Ptolemy XIII of Egypt upon the great Roman general’s arrival as he sought refuge following his defeat by Julius Caesar in the Roman Civil War.

“During his long career, Pompey the Great displayed exceptional military talents on the battlefield. He fought in Africa and Spain, quelled the slave revolt of Spartacus, cleared the Mediterranean of pirates, and conquered Armenia, Syria and Palestine. Appointed to organize the newly won Roman territories in the East, he proved a brilliant administrator,” writes The History Channel.

“In 60 BC, he joined with his rivals Julius Caesar and Marcus Licinius Crassus to form the First Triumvirate, and together the trio ruled Rome for seven years. Caesar’s successes aroused Pompey’s jealousy, however, leading to the collapse of the political alliance in 53 B.C. The Roman Senate supported Pompey and asked Caesar to give up his army, which he refused to do. In January 49 B.C., Caesar led his legions across the Rubicon River from Cisalpine Gaul to Italy, thus declaring war against Pompey and his forces.

Caesar made early gains in the subsequent civil war, defeating Pompey’s army in Italy and Spain, but he was later forced into retreat in Greece. In August 48 B.C., with Pompey in pursuit, Caesar paused near Pharsalus, setting up camp at a strategic location. When Pompey’s senatorial forces fell upon Caesar’s smaller army, they were entirely routed, and Pompey fled to Egypt.”

There the great general was met with betrayal from his former ally. “Pompey’s arrival on Ptolemy XIII’s doorstep left Ptolemy’s advisors in an awkward position, explains History Hit. “The Egyptians knew that they owed the man. But they also knew that Caesar was in pursuit. Feeling obliged to open their doors to Pompey, yet seeking to align themselves with the winner of the civil war, Ptolemy’s regent – a eunuch named Pothinus – devised a strategy that would win Egypt the favour of Julius Caesar.

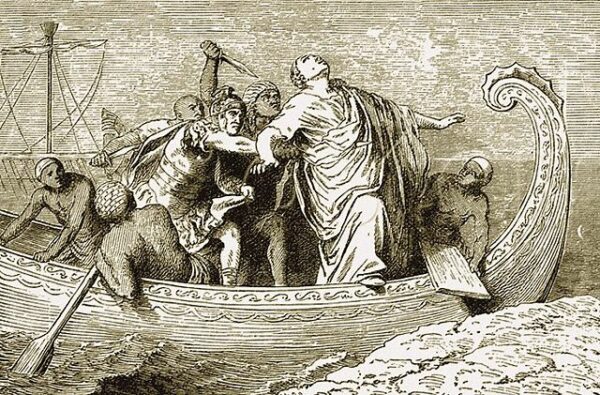

Septimius, head of the Egyptian army, sailed to Pompey the Great’s ship on a meager fishing boat with a few military men. Pompey’s wife and advisors sensed trouble; they pleaded with him not to embark on the tiny vessel. Upon boarding and being shown a galling lack of respect, Pompey asked Septimius: “Am I mistaken, or were you not once my fellow soldier?”. Septimius’s response was to nod once soberly, making no reply, according to Plutarch.

Septimius then drove a sword into Pompey. The others on the boat then moved in too with their own daggers to finish the job. Plutarch wrote, that, at the moment of assassination, Pompey “[drew] his toga over his face with both his hands, and neither saying nor doing anything unworthy of himself […] endured their blows, having lived for fifty-nine years, and ending his life one day after his birthday.”

Pompey’s body was burned, but his head was saved for proof of his death. Only later was it returned to his wife for burial at his villa in the Alban Hills. His ignominious death prompted Cicero to write that “his life outlasted his power.”

The assassination of Pompey was a tragic end for a man who had once been a symbol of Roman power and prestige. It symbolized the brutal realities of Roman politics, where alliances were constantly shifting, and individuals were often discarded when they were no longer useful. Pompey’s death also paved the way for Julius Caesar’s continued rise to power, further consolidating his control over the Roman Republic.

Pompey’s death had far-reaching consequences for the Roman Republic. With the death of his major rival, Caesar’s path to becoming the de facto ruler of Rome was clear, and the republic was inching closer to its eventual transformation into the Roman Empire.