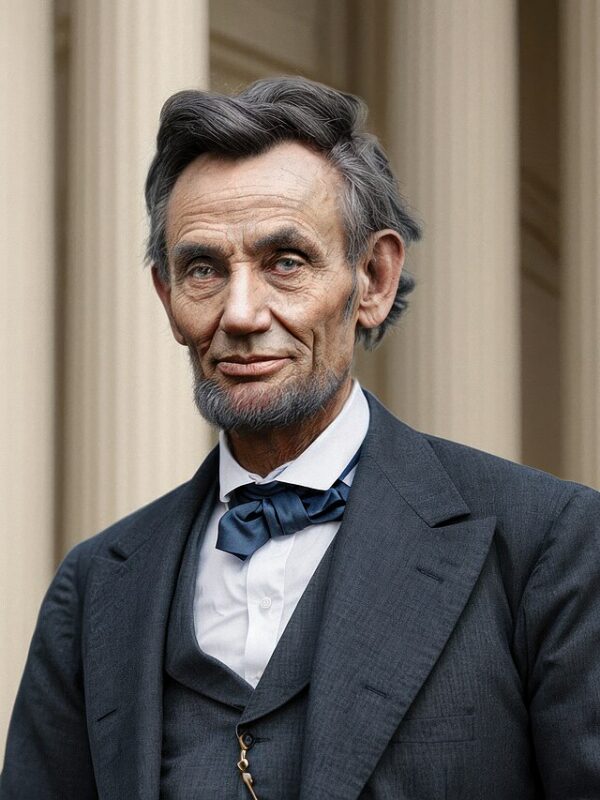

On November 8, 1861, the Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward found themselves caught in one of the most important diplomatic conflicts during the Civil War. Called the “The Trent Affair,” the incident involved the interception of a British mail steamer, the RMS Trent, by the USS San Jacinto, a Union warship. The Trent was carrying Confederate diplomats James Mason and John Slidell to Europe in an attempt to gain support for the Confederate States of America. The incident raised tensions between the United States and Great Britain, potentially bringing them to the brink of war.

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America, had dispatched these envoys—James Mason, former Chairman of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee and John Slidell, a prominent New Orleans lawyer—to secure British and French recognition of the Confederate States as a sovereign nation. Great Britain and France had maintained their diplomatic relations with the United States following the outbreak of the Civil War and had recognized the Confederacy as a belligerent power, but not a sovereign government, in early 1861. Davis sought to change this by negotiating with these nations for full diplomatic recognition. Official diplomatic recognition by Britain and France would not only lend credibility to the Confederacy’s bid for independence but would also pave the way for lucrative trade deals between the Confederate States and the European powers. Davis hoped that recent Confederate victories against Union troops would favorably dispose British and French officials to receive his envoys, writes The State Department.

In October 1861, Mason and Slidell slipped through the U.S. naval blockade and left Charleston, South Carolina for Cuba, where they took passage for England on the Trent. U.S. Captain Wilkes intercepted the Trent on November 8, 1861 and, without permission from Washington, ordered his lieutenant to board and search the ship. The U.S. boarding party took Mason, Slidell, and their secretaries as prisoners, but allowed the Trent to depart for England.

Initial reaction on both sides of the Atlantic was strong. The United States, still smarting from the defeat at Bull Run during the summer, publicly celebrated this turn of events as a victory against the Confederacy and a blow to Confederate diplomacy. The British, on the other hand, strongly protested Wilkes’s action as illegal and a violation of their neutrality and demanded the release of the captive Confederate envoys as well as a formal apology. Although British officials continued to advocate a policy of neutrality, they did order troops to Canada and additional ships to the Western Atlantic. Neither the United States nor Great Britain wanted war, but it was clear that, at best, the Trent incident had sparked a major diplomatic disagreement and, at worst, appeared to have pushed Great Britain and the United States toward the potential for armed conflict.

Thanks to a communication malfunction, the cable containing the severe early reaction and demands of British officials took almost a month to arrive in Washington. By then, emotions had cooled on both sides and a more balanced view of the situation prevailed. Nevertheless, the British still expected a response from President Abraham Lincoln and continued to emphasize that Captain Wilkes had acted without official authorization.

Abraham Lincoln deftly managed the Trent Affair, a diplomatic crisis during the American Civil War, with a cautious and diplomatic approach. He sought legal advice, consulted his cabinet, and ultimately decided to release the diplomats, James Mason and John Slidell, recognizing the violation of British neutrality. This decision, accompanied by an official apology, averted a direct military conflict with the British Empire, and likely saved the Union, showcasing the Great Emancipator’s ability to navigate international relations and maintain peace during the most tumultuous period in American history.