On November 16, 1532, the Andean city of Cajamarca became the setting for one of history’s most dramatic and consequential encounters. A small band of Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro captured the Inca Emperor Atahualpa, an event that marked the beginning of the end for the vast and powerful Inca Empire. The audacity, strategy, and sheer brutality of the Spaniards that day forever altered the course of South American history.

Francisco Pizarro, driven by tales of immense wealth and the promise of glory, had set out to conquer the Inca Empire with the blessing of the Spanish Crown. By 1532, the empire was weakened by internal turmoil, as Atahualpa had recently emerged victorious in a bloody civil war against his half-brother, Huáscar. This division created an opportune moment for Pizarro, whose force of just 168 men stood in stark contrast to the tens of thousands of Inca warriors commanded by their emperor. However, Pizarro possessed a decisive technological edge: steel weapons, firearms, and horses, tools of war unknown to the Inca.

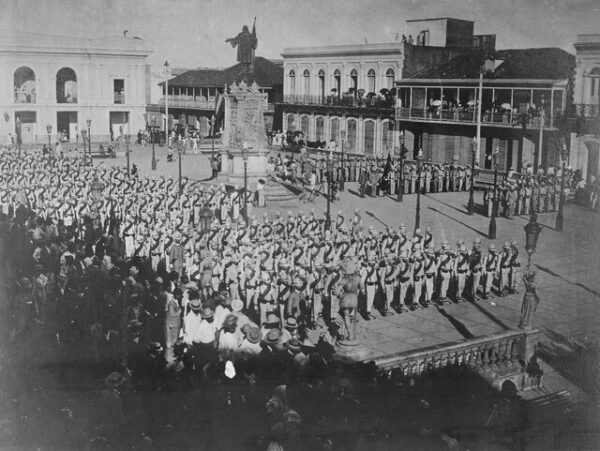

When Pizarro’s expedition reached Cajamarca, they found Atahualpa encamped nearby with a massive but celebratory force. The emperor, confident in his divine status and military might, agreed to meet the Spaniards in the city’s central square. Pizarro, however, had no intention of engaging in diplomacy. He orchestrated an elaborate ambush, positioning his men in concealed locations around the square and preparing them for a sudden and overwhelming assault.

Atahualpa arrived in the square on a ceremonial litter, surrounded by thousands of unarmed attendants dressed in their finest regalia. The Spaniards, observing the scene from their hiding places, remained calm as a Dominican friar approached the emperor to deliver a message. The friar offered Atahualpa a Bible and urged him to accept Christianity and submit to the authority of the Spanish Crown. Atahualpa, either out of curiosity or disdain, reportedly cast the book aside, an act interpreted by the Spaniards as an affront to their faith and their king.

This moment served as the trigger for the Spanish ambush. Pizarro’s men erupted from their positions, firing muskets, charging on horseback, and wielding steel swords with deadly efficiency. The sudden onslaught caused chaos among the Inca, who were unprepared and unable to defend themselves against the Spaniards’ superior weaponry and tactics. Horses, never before seen by the Inca, sowed additional panic, as the Spaniards used them to charge through the terrified crowd.

Amid the carnage, Pizarro himself captured Atahualpa, seizing the emperor from his royal litter in the chaos. By nightfall, thousands of unarmed Inca had been killed, while the Spanish suffered minimal losses. The audacious attack had not only decimated the Inca force but also left the empire without its leader, placing Atahualpa firmly in Spanish custody.

In the weeks that followed, Atahualpa sought to secure his release by offering a ransom of unimaginable scale. He pledged to fill a room with gold and provide two additional rooms of silver. Over several months, vast quantities of treasure were collected and delivered to the Spaniards, enriching them beyond their wildest dreams. Yet despite this extraordinary ransom, Pizarro and his men decided that Atahualpa was too great a threat to be left alive. In August 1533, after a mock trial, the emperor was executed by strangulation.

Atahualpa’s death marked the effective collapse of Inca resistance. Without their leader, the Inca were unable to mount a unified defense against the Spanish, who quickly consolidated their control over the empire.