On January 3, 1868, Japan experienced a transformative event that forever changed its political, social, and economic fabric—the Meiji Restoration. This monumental turning point marked the collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate, a feudal military government that had controlled Japan for over 260 years, and the beginning of imperial rule under Emperor Meiji. Spearheaded by influential leaders from the Satsuma and Chōshū domains, this political revolution sought to restore the emperor’s power and propel Japan into an era of modernization and global prominence.

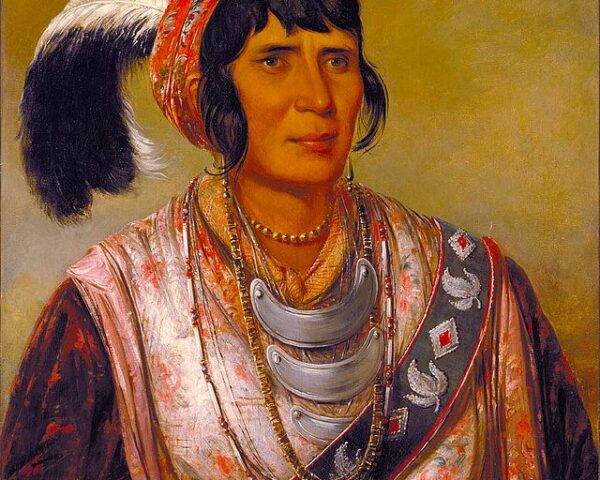

The Tokugawa shogunate, established in 1603 by Tokugawa Ieyasu, maintained a strict class hierarchy and an isolationist policy known as sakoku (closed country). For centuries, Japan remained largely sealed off from the outside world, allowing limited trade only through select Dutch and Chinese merchants in Nagasaki. However, Japan’s isolation was shattered in 1853 when Commodore Matthew Perry arrived with a fleet of American “Black Ships”. The shogunate, unable to resist foreign military power, was forced to sign unequal treaties with Western nations. This capitulation caused widespread resentment, especially in powerful regions like Satsuma and Chōshū, where leaders accused the Tokugawa government of failing to protect Japan’s sovereignty and honor.

Financial troubles compounded the shogunate’s struggles. Economic stagnation, repeated crop failures, and rising inflation left Japan’s economy in turmoil. Meanwhile, the samurai class, once proud warriors, became increasingly impoverished and disillusioned. Amid this crisis, reformist factions in Satsuma and Chōshū began rallying around the slogan sonnō jōi (Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians), calling for the restoration of imperial power and the expulsion of foreign influences.

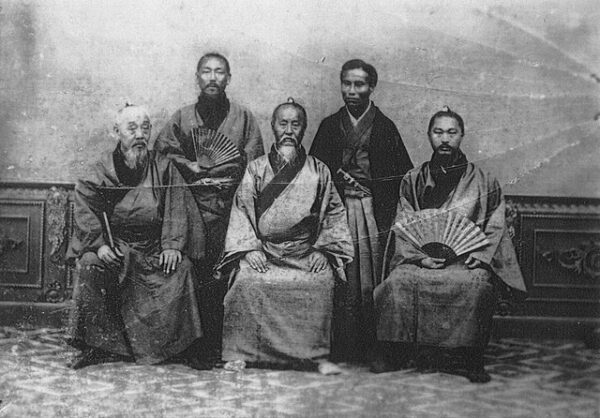

The domains of Satsuma (modern-day Kagoshima) and Chōshū (modern-day Yamaguchi) emerged as powerful centers of anti-shogunate sentiment. Frustrated by the Tokugawa regime’s mismanagement and emboldened by their military strength, the two regions formed a secret alliance in 1866 to oppose the shogunate. Leaders such as Saigō Takamori of Satsuma and Kido Takayoshi of Chōshū envisioned a Japan free from shogunal rule, united under a restored imperial authority. Their combined political and military efforts set the stage for an eventual confrontation with the Tokugawa government.

In late 1867, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the 15th and final shogun, attempted to ease tensions by voluntarily relinquishing political power to the emperor while hoping to retain Tokugawa influence in a reformed government. However, the Satsuma-Chōshū alliance was not content with partial reform and pushed for a complete dismantling of the Tokugawa system.

On January 3, 1868, agents of Satsuma and Chōshū took decisive action by seizing control of the Imperial Palace in Kyoto. They declared the restoration of imperial rule, placing Emperor Meiji, then a 15-year-old boy, at the head of the new government. The coup was swift and largely bloodless but sparked a broader conflict known as the Boshin War. Pro-shogunate forces, unwilling to accept the new imperial regime, launched a series of military campaigns against imperial troops.

The conflict culminated in several key battles, including the Battle of Toba-Fushimi, where imperial forces—armed with Western weaponry and tactics—decisively defeated Tokugawa loyalists. By mid-1869, the remaining Tokugawa forces had been crushed, and Yoshinobu formally surrendered, marking the definitive end of the Tokugawa shogunate.

The Meiji Restoration was far more than a political coup—it represented the beginning of Japan’s rapid modernization. The new imperial government implemented sweeping reforms across various sectors, including the abolition of the feudal domain system, the creation of a modern national army through universal conscription, and ambitious infrastructure projects such as railroads and telegraph networks. Compulsory education was introduced, emphasizing literacy, science, and loyalty to the emperor. Additionally, Japan adopted Western technologies, legal systems, and industrial practices while carefully preserving essential aspects of Japanese culture and tradition.

The once-dominant samurai class was stripped of its traditional privileges, and Japan’s social structure underwent profound changes to align with modern state-building ideals.

The Meiji Restoration set Japan on an unprecedented trajectory of growth. Within a few decades, Japan transformed into an industrialized global power, capable of competing with Western nations on equal footing. This rapid modernization became a symbol of Japan’s adaptability and resilience. However, the era also planted the seeds of Japanese imperialism, as the drive for modernization and national strength evolved into expansionist ambitions in East Asia.

The events of January 3, 1868, remain one of the most defining moments in Japanese history—a day when visionary leaders from Satsuma and Chōshū dismantled an ancient order and laid the groundwork for Japan’s emergence as a modern nation-state. The Meiji Restoration is not just a story of political upheaval; it is a testament to the power of leadership, vision, and the ability to adapt in the face of immense challenges.