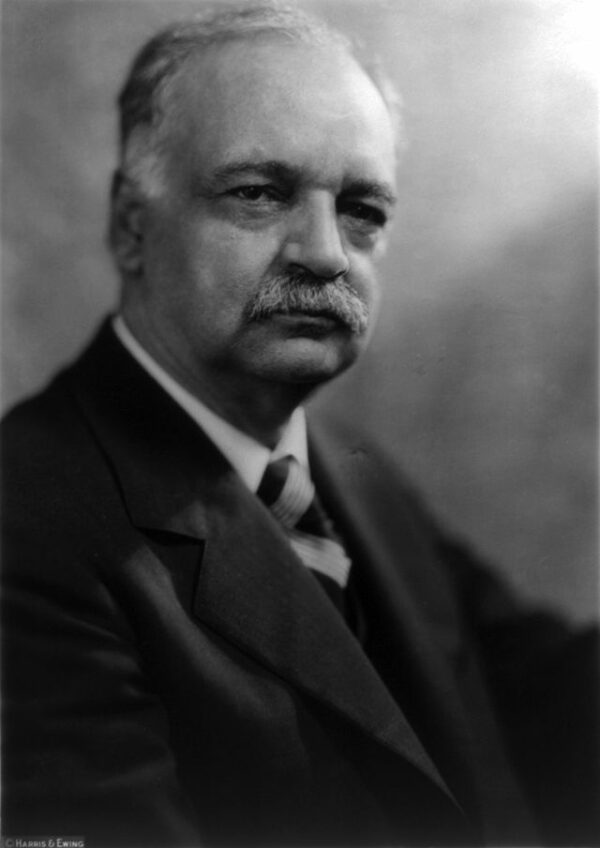

Charles Curtis made history on January 29, 1907, becoming the first Native American to serve in the United States Senate. A member of the Kaw Nation, Curtis’s extraordinary career was marked by his dedication to public service, his advocacy for Native American issues, and his eventual rise to become Vice President of the United States under Herbert Hoover.

Born on January 25, 1860, in North Topeka, Kansas, Curtis grew up in a culturally diverse environment that shaped his character and values. His mother, Ellen Papin, was of Kaw, Osage, and French descent, while his father, Orren Curtis, was of European ancestry. After his mother’s death during his childhood, Curtis spent part of his youth with his maternal grandparents on the Kaw reservation. There, he learned to speak Kanza, the language of the Kaw people, and embraced his Native heritage. Although Curtis later supported policies that some saw as detrimental to tribal sovereignty, he often credited his upbringing among the Kaw people for his sense of determination and resilience.

Curtis’ path to politics was far from conventional. Before entering public service, he worked as a jockey, earning recognition for his skills on the Midwest racing circuit. Later, he turned to law, gaining admission to the bar in 1881 and building a reputation as a skilled and effective attorney in Topeka. His natural charisma and ability to connect with people from different backgrounds quickly propelled him into public office.

In 1893, Curtis was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served until 1907. His tenure coincided with significant social and economic changes in the country, and he became a strong advocate for the agricultural interests of Kansas. Despite his Native heritage, Curtis supported policies such as the Dawes Act, which aimed to assimilate Indigenous peoples by redistributing tribal lands into individual allotments. Curtis argued that such measures were essential for Native Americans to thrive in a modern America, though historians have since criticized these policies for undermining tribal autonomy and identity.

In 1907, Curtis was elected to the U.S. Senate, becoming the first Native American to serve in this role. He served for nearly two decades, with a brief return to the House of Representatives in 1913. During his time in the Senate, Curtis was a member of the Republican Party and supported progressive reforms, including women’s suffrage and protections against child labor. His reputation as a skilled negotiator helped him build bipartisan coalitions to pass legislation addressing economic development and infrastructure, particularly benefiting the Midwest.

In 1924, Curtis became the Senate Majority Leader, a role in which his talent for building consensus shone. He approached leadership with pragmatism, believing in compromise as a key tool for governance. His deep understanding of legislative processes and ability to navigate political challenges made him an effective leader during a dynamic period in American politics.

Curtis’s political career reached its peak when he was elected Vice President of the United States in 1928 as Herbert Hoover’s running mate. Sworn into office on March 4, 1929, Curtis became the first person of Native American ancestry to hold the vice presidency. During his tenure, he sought to represent the interests of rural America while navigating the immense challenges of the Great Depression. Despite his efforts, the Hoover administration faced widespread criticism for its handling of the economic crisis, which overshadowed Curtis’s contributions.

After leaving office in 1933, Curtis retired from politics but remained active in public life, offering speeches and reflections on his lengthy and groundbreaking career. He passed away on February 8, 1936, leaving behind a legacy of trailblazing achievements. While his support for certain policies remains a point of contention, Curtis’s rise from the Kaw reservation to one of the highest offices in the nation is a powerful testament to his determination and resilience.