On February 20, 1943, The Saturday Evening Post published the first of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings, a series of illustrations inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union address. In that speech, Roosevelt outlined his vision for a world based on four essential human rights: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear. These principles, set against the backdrop of World War II and the global fight against fascism, became central to the moral justification of the American war effort. Rockwell’s paintings provided a vivid visual representation of these ideals, reinforcing patriotic sentiment and encouraging public support for the war.

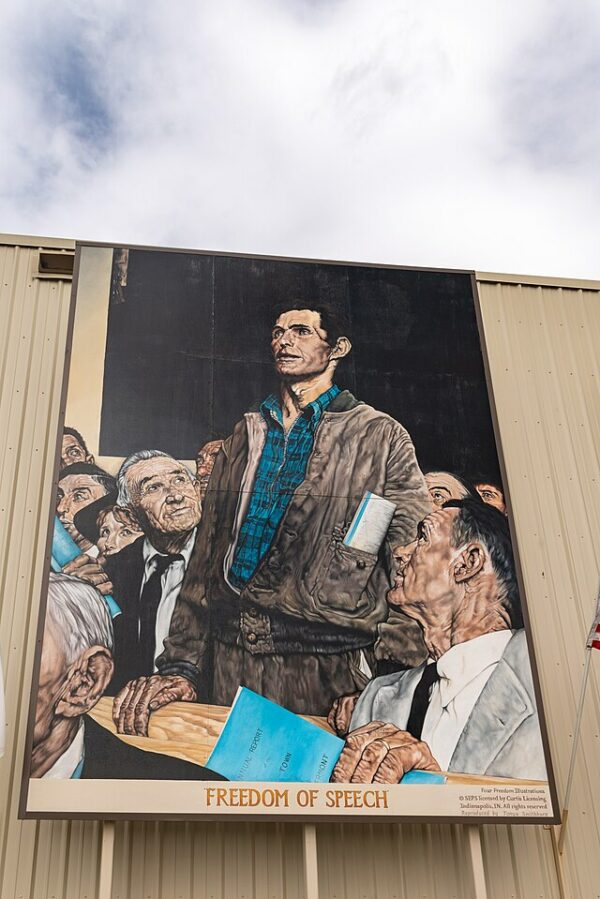

The first painting in the series, Freedom of Speech, appeared in The Saturday Evening Post. It depicts an ordinary working-class man standing to speak at a town hall meeting, symbolizing the democratic ideal of free expression. Dressed in a simple plaid shirt and work jacket, he holds a folded document in his pocket, possibly representing a petition or personal statement, while those around him listen attentively. By portraying a regular citizen rather than a political leader or soldier, Rockwell emphasized that democracy belongs to everyone, not just the powerful. The realistic style and warm tones of the painting conveyed both familiarity and an aspirational vision of American civic life.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms series emerged at a critical moment in American history. By early 1943, the United States was deeply engaged in the war, but public morale needed reinforcement. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms had initially been introduced as part of a broader argument for American involvement in World War II, positioning the conflict as more than just a battle against enemy nations—it was a fight to uphold fundamental human rights. However, political rhetoric alone was not enough to inspire mass mobilization. Rockwell’s illustrations made these abstract ideals tangible, presenting them in relatable, human-centered narratives.

Moved by Roosevelt’s address, Rockwell proposed the idea of illustrating the Four Freedoms to the U.S. government, hoping to contribute his artistic skills to the war effort. Initially, the Office of War Information rejected his proposal, but The Saturday Evening Post, where Rockwell had been a regular illustrator for years, welcomed the idea enthusiastically. The magazine published the paintings in four consecutive weekly issues, beginning with Freedom of Speech on February 20. Each image was accompanied by an essay from a notable American writer, reinforcing themes of democracy, security, and national unity.

The response from the American public was overwhelming. Rockwell’s images resonated deeply, affirming the values that many saw as worth defending in wartime. Due to the series’ popularity, the U.S. Treasury Department later incorporated the Four Freedoms into a national war bond campaign. The paintings were exhibited across the country, drawing millions of viewers and helping to raise over $132 million for the war effort.

Beyond their immediate impact during World War II, Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings have remained significant cultural symbols of American democracy. They have been widely reproduced in textbooks, posters, and museum exhibits, shaping public memory and discussions on human rights. However, their legacy has not gone unchallenged. Scholars and activists have pointed out that the series predominantly reflects an idealized, white, middle-class America, overlooking the racial and economic disparities of the time. Despite this, Rockwell’s ability to translate political ideals into emotionally powerful imagery demonstrates the enduring influence of art in shaping public perception.

Ultimately, Rockwell’s Four Freedoms, beginning with Freedom of Speech in February 1943, provided a compelling visual affirmation of Roosevelt’s call for a world founded on fundamental liberties. They offered a unifying narrative for the American war effort, reinforcing the idea that the sacrifices of World War II were made in the service of a greater moral purpose.