On April 14, 43 BC, Roman legions loyal to the Senate clashed with the forces of Mark Antony in a pivotal engagement near the northern Italian village of Forum Gallorum. The battle was not merely a contest of arms—it was a violent reckoning in the wake of Julius Caesar’s assassination, one that laid bare the unraveling political order and the ambitions surging in its place.

In the months following Caesar’s death, Rome slid into a dangerous power vacuum. Mark Antony, determined to claim the mantle of Caesar’s legacy, moved swiftly to seize control of Cisalpine Gaul—a strategic province then under the command of Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, one of Caesar’s assassins. Antony’s decision to lay siege to Brutus in Mutina (modern Modena) forced the Senate’s hand. Alarmed by the threat, they dispatched both consuls, Gaius Vibius Pansa and Aulus Hirtius, to break the siege, accompanied by Caesar’s young adopted heir, Gaius Octavius.

Antony understood the threat posed by these converging forces and struck preemptively. At dawn on April 14, he launched an ambush on Pansa’s column. The Senate’s troops, many of them inexperienced, were caught unprepared. The result was a bloody rout. Pansa was gravely wounded and evacuated from the field, while his forces were shattered. In the immediate aftermath, Antony appeared poised for a decisive victory.

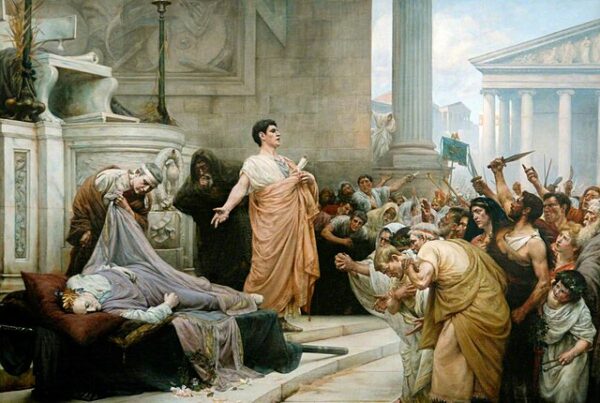

But the tide turned. Hirtius, commanding a fresh and disciplined contingent, arrived as Antony’s troops were reassembling. Exploiting the moment, Hirtius ordered a sudden counteroffensive. His veterans tore through Antony’s ranks, reclaiming legionary standards and Roman eagles—sacred emblems whose recovery restored morale and prestige. Forced into retreat, Antony abandoned the field. The Senate’s forces, though bloodied, had secured a hard-fought triumph.

The cost of that victory, however, was steep. Pansa succumbed to his wounds days later. Hirtius, too, would die in the ensuing combat outside Mutina. In the vacuum left by their deaths, the unlikely figure of Octavian emerged as the Senate’s last remaining general—a twenty-year-old with no formal office but an unassailable claim to Caesar’s name.

What followed was not the restoration of republican order but its further erosion. Octavian, sensing the weakness of the Senate, turned their dependence into leverage. By the end of the year, he would align himself with Antony and Lepidus, forming the Second Triumvirate and seizing extraordinary powers. The Republic was no longer merely faltering—it was being replaced.

The Battle of Forum Gallorum was more than a tactical episode; it marked the moment when military allegiance eclipsed civic deliberation as the engine of Roman politics. The Republic, mortally wounded, would not recover.