On May 2, 1611, in the heart of London, England, printer Robert Barker released the first edition of what would become one of the most influential and widely read books in the English-speaking world: the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible. Commissioned by King James I of England in 1604, the translation was intended to unify religious practice across his kingdom and replace the various competing English versions of Scripture then in circulation. Over four centuries later, its literary legacy endures, and its theological influence remains deeply woven into Protestant tradition.

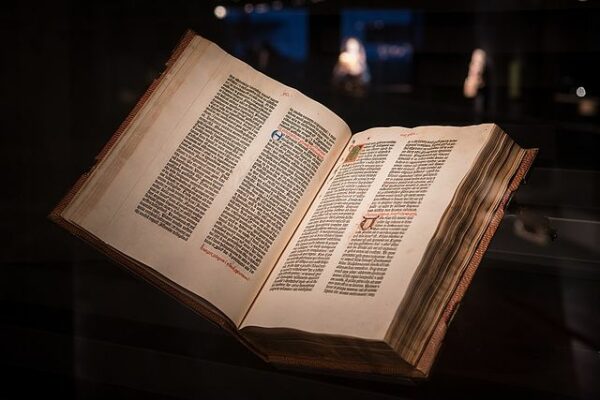

The King James Bible was not the first English translation. Preceding versions by John Wycliffe in the 14th century and William Tyndale in the early 16th century had already brought the scriptures to the English-speaking laity, often at great personal cost. Tyndale, for instance, was executed for translating the Bible without ecclesiastical approval. But by the time of James I’s reign, English translations had gained broader, though still contested, acceptance. The Geneva Bible, produced by English Protestant exiles during the reign of Mary I, had become popular, especially among Puritans, but was viewed with suspicion by the Anglican establishment for its marginal notes critical of monarchy. The Bishops’ Bible, an official Church of England version, lacked Geneva’s popularity and accessibility.

Recognizing the need for a unifying and authoritative text, King James I convened the Hampton Court Conference in 1604, where Puritan leaders petitioned for reforms in worship and governance. While James rejected most of their demands, he agreed to one key request: a new Bible translation devoid of partisan annotations. He appointed a committee of over 50 scholars and churchmen—linguists, theologians, and academics—divided into six companies, each assigned specific portions of the Old and New Testaments and the Apocrypha. Working in teams based at Oxford, Cambridge, and Westminster, they labored for seven years, cross-checking their translations with Hebrew and Greek manuscripts, as well as earlier English editions.

The resulting translation was not only a theological work but a linguistic masterpiece. Drawing on the stately cadences of Tyndale and the Geneva Bible, the KJV sought to balance poetic beauty with doctrinal clarity. It preserved the majesty of biblical language while adhering to a principle of “formal equivalence”—translating word-for-word as closely as possible to the original languages. Its phrasing—”Let there be light,” “the powers that be,” “by the skin of your teeth”—entered the vernacular, shaping English literature, rhetoric, and religious discourse for centuries.

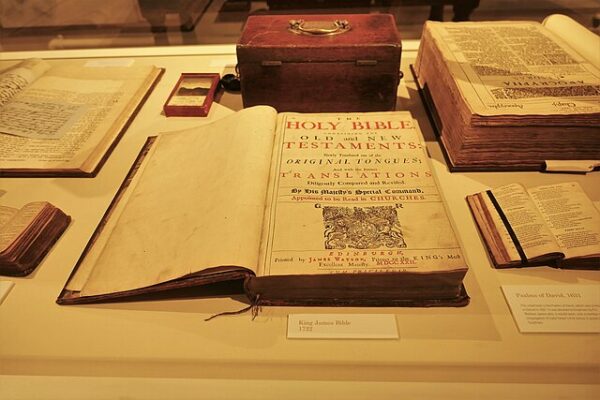

Robert Barker, the King’s Printer, was responsible for publishing the first folio edition. That 1611 printing was a large and costly volume, designed primarily for use in churches rather than for individual ownership. In fact, early printings were riddled with typographical errors—perhaps the most infamous being the “Wicked Bible” of 1631, in which the commandment “Thou shalt not commit adultery” appeared without the word “not.” Despite such setbacks, the KJV quickly spread throughout England and its colonies, becoming the dominant English Bible by the mid-17th century.

The King James Bible was not simply a religious document; it became a cultural foundation. It influenced writers from John Milton to William Blake, Abraham Lincoln to Martin Luther King Jr., who quoted it in some of his most iconic speeches. It also helped standardize English spelling and grammar during a period of great linguistic flux.

Though modern translations have gained ground in recent decades, especially among evangelicals and scholars seeking greater fidelity to ancient texts, the King James Version continues to be revered for its majesty and historical significance. Published in an era of religious conflict and national transformation, the KJV was both a product of its time and a transcendent literary work. Its first appearance in print on May 2, 1611, marked not just a milestone in religious history, but a defining moment in the development of the English language and the global Christian tradition.