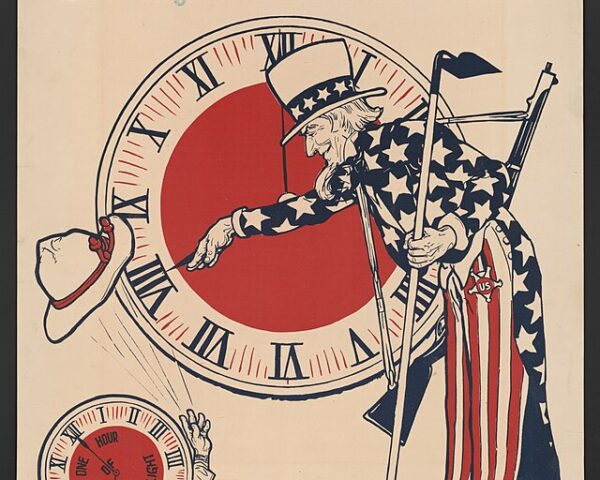

On May 18, 1933, as the economic catastrophe of the Great Depression continued to erode confidence in the American system, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law the Tennessee Valley Authority Act—a legislative cornerstone of the New Deal and a radical assertion of federal authority in economic planning, environmental stewardship, and regional uplift. The act did not merely create a public corporation; it inaugurated what Roosevelt and his advisors envisioned as a “bold experiment”—an interventionist model of technocratic governance designed to rescue one of the nation’s most impoverished and environmentally degraded regions.

The Tennessee Valley—stretching across seven states, including Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, and parts of Kentucky, Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia—represented, in the eyes of New Dealers, the quintessential case study in market failure. Plagued by deforestation, recurrent flooding, overfarmed soil, and a near-total absence of electrification, the region had long remained outside the arc of industrial modernity. In 1933, fewer than one in thirty rural households in the area had access to electricity. The private utilities, which might have extended power to these communities, had failed to do so—restrained, perhaps, by the limits of profitability, but also, more damningly, by a deliberate strategy of monopolistic pricing and exclusion. Here, Roosevelt saw not just a humanitarian emergency, but an opportunity to prove that government, armed with science and guided by public purpose, could do what capital had refused to attempt.

At its core, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was an effort to reclaim the Tennessee River basin—not only for energy production, but as an engine of economic renewal. Authorized to construct hydroelectric dams, regulate river navigation, mitigate floods, reforest depleted lands, and sell electricity at cost, the TVA fused the power of the state with the logic of the engineer. It marked a decisive departure from laissez-faire orthodoxy, embedding the federal government directly in the business of energy markets, regional development, and environmental management.

The early achievements of the TVA were dramatic and highly visible. Within a few years, monumental dams rose across the valley—Norris, Wheeler, and Pickwick Landing, among others—harnessing the river’s flow to generate electricity, prevent seasonal floods, and create thousands of desperately needed jobs. These projects were more than feats of engineering; they were symbols of Roosevelt’s broader project of national revitalization, proof that the New Deal could transform marginal regions into productive landscapes. The arrival of affordable electricity—once a luxury reserved for urban elites—revolutionized life for rural families, enabling refrigeration, lighting, mechanized farming, and, perhaps most importantly, the psychological shift from isolation to inclusion in the modern American economy.

Yet the TVA was also a political provocation. Its very existence challenged the sanctity of private enterprise. Investor-owned utilities decried the agency as a “socialist” affront, a publicly subsidized competitor that distorted the market. Lawsuits were filed. Congressional hearings were held. But Roosevelt—backed by progressive reformers like Senator George Norris and administrators like David Lilienthal—pressed forward, arguing that the public good could not be held hostage to the balance sheets of monopoly firms. The U.S. Supreme Court would eventually uphold the TVA’s constitutionality, but the deeper victory was ideological: a redefinition of what government could, and should, be entrusted to do in the face of crisis.

The TVA also offered a prototype for technocratic governance. Its staff included not just engineers and administrators, but agronomists, public health officials, educators, and social scientists. Together they conducted soil surveys, introduced crop rotation and erosion control techniques, distributed seedlings, vaccinated against malaria, and taught farmers how to adopt modern methods. In this sense, the TVA was not simply a utility—it was a state-sponsored laboratory of modernization, where science, policy, and democracy intersected to reshape both the land and the lives of those who inhabited it.

By the outbreak of the Second World War, the Tennessee Valley had been irrevocably altered. The agency’s hydroelectric output fueled war industries, including aluminum production critical to aircraft manufacturing. Its infrastructural legacy—cheap power, stable waterways, improved farmland—positioned the region for long-term industrial growth. But perhaps its most enduring impact was moral and political: it demonstrated that the federal government, when wielded competently and with ambition, could act as a constructive force in the lives of ordinary Americans.

Thus, the TVA’s creation on May 18, 1933, did more than address the immediate emergencies of flood, poverty, and unemployment. It inaugurated a new era of American governance—one in which the state assumed a proactive role in shaping markets, stewarding natural resources, and redefining the possibilities of collective action.