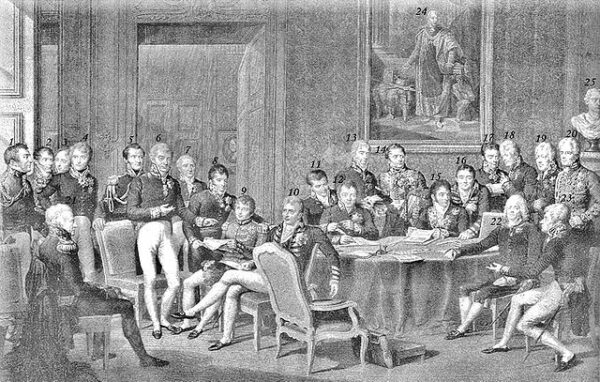

The Congress of Vienna, whose Final Act was signed on June 9, 1815, did not merely redraw borders—it sought to rewind the age. In the waning shadow of Napoleon’s first fall and on the eve of his improbable return, Europe’s old monarchies assembled not only to restore stability but to extinguish the ideological wildfire that had spread since 1789. The ambition was not peace alone, but restoration—of thrones, of dynasties, of a worldview shattered by revolution. And in this, they succeeded—at least for a time.

Presided over by Austria’s Prince Klemens von Metternich—a man whose cold devotion to order approached metaphysical certainty—the Congress was an exercise in reactionary statecraft, a diplomatic exorcism against the specters of popular sovereignty and national self-determination. The French Revolution had unseated kings, raised citizen-armies, and dared to claim that legitimacy derived not from God or bloodline but from the governed. The wars that followed—nearly twenty years of blood and fire—were seen by the assembled powers not as the product of monarchical miscalculation, but as the wages of ideology. The answer, then, was not reform. It was reversal.

France, though defeated, was spared dismemberment—not out of mercy, but geometry. To humiliate her too deeply was to invite the very forces of vengeance the Congress aimed to suppress. The Bourbons were restored, and France’s borders were drawn back to their 1792 limits. Prussia, in turn, received the Rhineland and parts of Saxony—a bulwark against French resurgence. Austria reclaimed Lombardy and Venetia, extending its grip over northern Italy. Russia absorbed most of Poland, styling it a “Kingdom” under Tsar Alexander’s personal rule. Britain, aloof as always from continental entanglements, secured the global periphery: Cape Colony, Ceylon, and control of the seas.

But territorial adjustment was only the surface. Beneath it lay an ideological counter-revolution. Metternich and his peers did not merely oppose change—they feared its very logic. Constitutionalism, democracy, the rights of nations—these were not political ideas but contagions, capable of toppling kingdoms from within. To safeguard Europe, a system was devised: the Concert of Europe, a self-appointed brotherhood of empires committed to mutual defense—not against invasion, but insurrection. Peace would not be kept by law but by alliance; legitimacy would be guarded by force.

The Congress created neutralized zones—Switzerland, the Low Countries—buffer states designed to contain France and dilute the currents of nationalism. The Holy Roman Empire, long defunct, was replaced by the German Confederation—a loose patchwork of 39 states under Austrian supervision, a shield against both French ambition and German unification. The message was clear: identity was to be dynastic, not ethnic; loyalty owed upward, not outward.

Yet history, in its irony, would not wait. Even as the diplomats sealed their pact, Napoleon escaped Elba and returned to France—cheered by soldiers and citizens alike. The Hundred Days that followed briefly exposed the fragility beneath the Congress’s grand design. But Waterloo, and Napoleon’s final exile, provided a grim vindication. The old order, having narrowly survived, would now entrench itself with redoubled fervor.

For nearly a century, the system endured. No general war engulfed the continent until 1914. But the deeper tensions—nationalism repressed, liberalism denied, the peoples of Europe ruled but not heard—remained unresolved. The Congress of Vienna had silenced revolution, not answered it. And in doing so, it bought time—but not permanence. Beneath the polished symmetry of its map lay the fault lines of the modern age.