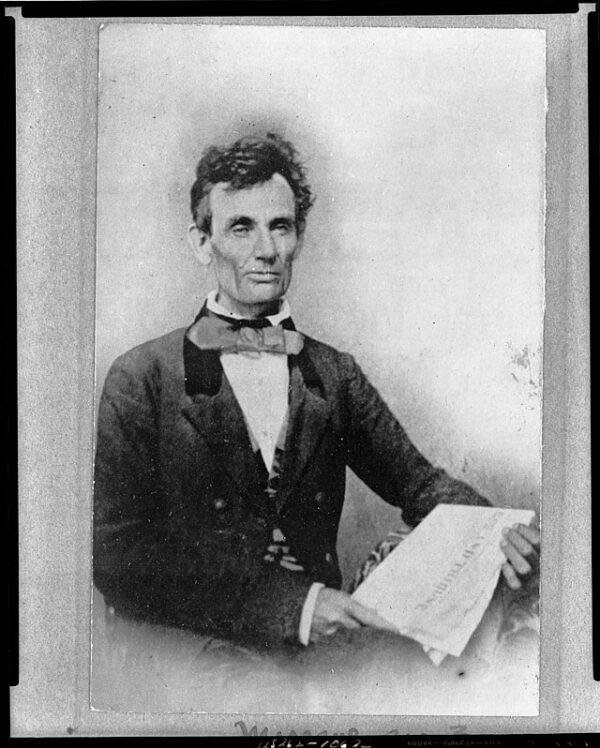

In the fading light of the evening on June 16, 1858, Abraham Lincoln stepped before the Illinois Republican Convention in Springfield and delivered a speech that startled even his allies with its moral clarity and stark prognosis. Accepting his party’s nomination for the United States Senate, Lincoln did not appeal to the center or couch his convictions in compromise. Instead, he issued a thunderclap of warning: “A house divided against itself cannot stand.”

With those opening words—drawn from the Gospel of Mark—Lincoln framed the sectional crisis not as a matter of political expedience, but as a test of the Republic’s moral foundations. “I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free,” he said, standing at the podium inside the Illinois State Capitol. “I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided.”

At the time, such language was incendiary. The nation was still reeling from the effects of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, authored four years prior by Lincoln’s Senate opponent, Stephen A. Douglas. That act had repealed the Missouri Compromise and opened new territories to the possibility of slavery under the principle of popular sovereignty. The result had been political chaos and violent skirmishes—most notably in “Bleeding Kansas”—as pro- and anti-slavery factions battled for control.

But Lincoln saw something deeper than factional violence. He discerned a coordinated march of events—political, legislative, and judicial—aimed at nationalizing slavery. He tied Douglas’s legislation directly to the 1857 Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which ruled that neither Congress nor territorial legislatures could ban slavery in federal territories. To Lincoln, these moves were not isolated misjudgments—they were milestones on a road toward making slavery “lawful in all the States, old as well as new.”

“We shall lie down pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free,” Lincoln warned, “and we shall awake to the reality instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave state.”

Even some Republicans in the audience squirmed. Many hoped the party could focus narrowly on stopping the expansion of slavery without challenging its existence in the South. But Lincoln refused to retreat into comfort. The crisis, he argued, was not one of geography, but of principle. One way or another, he insisted, the nation would resolve its contradiction: it would become all one thing, or all the other.

While the speech electrified his base, it handed ammunition to Democrats, who quickly accused Lincoln of stoking disunion and fanaticism. Douglas would seize on the rhetoric during their upcoming debates, painting Lincoln as a radical bent on disturbing the delicate balance of the federal compact. Ultimately, Lincoln lost the 1858 Senate race—not by popular vote, which he won—but through a legislative system that awarded the seat to Douglas via Democratic gains in downstate districts.

Yet Lincoln’s loss proved temporary. The “House Divided” speech marked a turning point—not just for Lincoln’s political future, but for the national debate over slavery. In confronting the moral contradictions of American democracy head-on, Lincoln separated himself from the equivocation of career politicians and announced himself as something rarer: a statesman willing to risk defeat for the sake of truth.

Within two years, he would be elected President. Within three, the house would indeed collapse into war. But Lincoln’s warning, spoken calmly that night in Springfield, would prove prophetic.