On July 4, 1863, while the Union celebrated Independence Day, General Ulysses S. Grant accepted the surrender of Confederate Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton at Vicksburg, Mississippi—concluding a grueling 47-day siege and securing one of the most decisive victories of the American Civil War. The fall of Vicksburg not only split the Confederacy in two by granting the Union full control of the Mississippi River, but also elevated Grant’s national stature, paving the way for his eventual command of all Union armies.

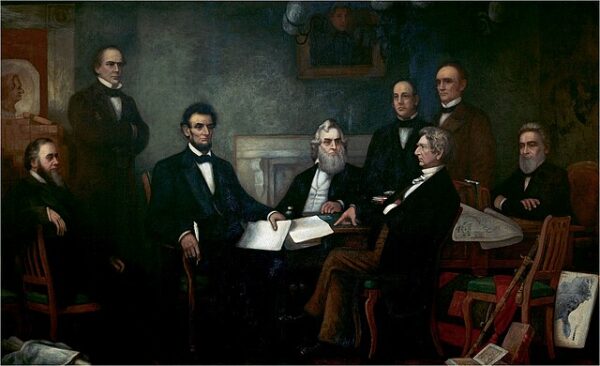

Vicksburg had long been considered the key to the South. Perched atop steep bluffs overlooking a sharp bend in the Mississippi, the city commanded the river’s shipping lanes and served as a vital logistical artery for Confederate supply lines. President Abraham Lincoln famously remarked, “See what a lot of land these fellows hold, of which Vicksburg is the key! The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket. We can take all the northern ports of the Confederacy, and they can defy us from Vicksburg.”

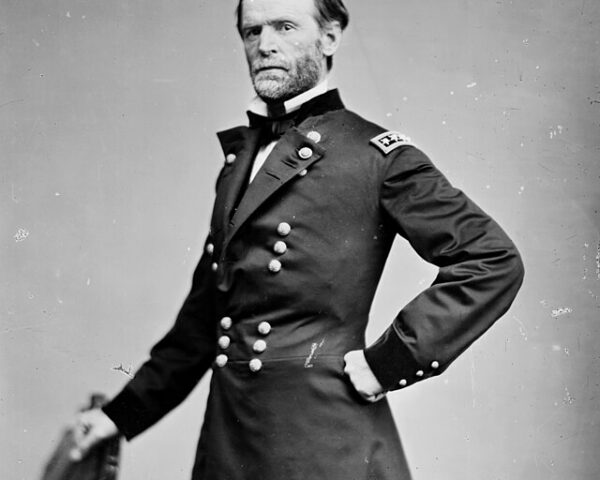

Grant’s campaign for Vicksburg was a masterpiece of maneuver and determination. Earlier Union attempts to seize the city from the north and west had floundered amid the region’s swamps, bayous, and dogged Confederate resistance. Grant, however, devised a bold plan: he marched his army down the western bank of the Mississippi, crossed south of Vicksburg at Bruinsburg, and moved inland to strike from the east. Between May and early July 1863, he executed a lightning campaign that defeated Confederate forces in a series of engagements—Port Gibson, Raymond, Jackson, Champion Hill, and Big Black River Bridge—before surrounding Vicksburg itself.

Once his troops had encircled the city on May 18, Grant launched two initial assaults, hoping to quickly overwhelm the defenders. Both failed with heavy losses, leading him to settle into siege operations. For the next six weeks, Union forces constructed a ring of trenches and artillery emplacements around Vicksburg, cutting the city off from supply and relief. Inside, 30,000 Confederate soldiers and tens of thousands of civilians endured constant shelling, disease, and starvation. Food grew so scarce that residents resorted to eating mules, dogs, and rats. Soldiers dug caves into the hillsides to escape bombardment, and the once-proud city deteriorated into a collection of craters, rubble, and desperation.

Despite repeated pleas for assistance, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston—commanding a nearby army in Mississippi—proved unable to mount a rescue. His reluctance to engage Grant’s larger and better-positioned force allowed the siege to grind toward its inevitable conclusion. Morale inside Vicksburg collapsed, and on July 3, Pemberton, realizing the hopelessness of further resistance, proposed terms of surrender. Grant, initially demanding unconditional surrender, ultimately agreed to parole the captured Confederates rather than take them prisoner—a practical decision that spared the Union army the logistical burden of feeding and transporting thousands of men.

The next day, July 4, the stars and stripes were raised over Vicksburg. News of the victory, arriving shortly after the Union triumph at Gettysburg, electrified the North. Though both battles were fought independently, their near-simultaneous outcomes marked a profound turning point in the war. The Union now held complete control of the Mississippi River, severing the Confederacy’s eastern and western halves and cutting off Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas from the rest of the Southern war effort. The Confederacy would never recover from this strategic blow.

For the South, the loss of Vicksburg was a catastrophe. Confederate President Jefferson Davis had once declared that the city was the “nailhead that held the South’s two halves together.” Its fall shattered the illusion of invincibility in the West and exposed the limitations of Confederate command coordination. For Grant, however, Vicksburg was a personal triumph—a vindication of his aggressive strategy and logistical prowess. Within a year, he would be summoned east to lead all Union armies against Robert E. Lee.