On July 16, 1861, at the direction of President Abraham Lincoln, thousands of Union soldiers crossed the Potomac River and began a grueling 25-mile march toward Manassas Junction, Virginia. The operation, undertaken with the hopes of swiftly crushing the Confederate rebellion, would culminate just days later in the First Battle of Bull Run—shattering illusions of a short war and exposing the raw realities of a nation at war with itself.

The order to advance came after weeks of mounting political and public pressure in the North. Newspapers, Congress, and citizens eager for a quick end to the rebellion clamored for action following the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter and the loss of federal control in much of the South. President Lincoln, though initially cautious, eventually authorized Brigadier General Irvin McDowell to move on Confederate forces under General Pierre G.T. Beauregard, who had concentrated his men near the critical railroad hub of Manassas.

McDowell’s army, consisting of roughly 35,000 largely untested volunteers, had been hastily assembled and only briefly drilled. Many of the men had enlisted for 90 days under the widespread belief that the conflict would be brief and decisive. Their uniforms were mismatched, their ranks filled with young clerks, farmhands, and shopkeepers—patriotic but green. As the columns set out under the sweltering July sun, some soldiers reportedly joked that the march to Manassas would be their one great adventure before returning home.

But the march itself quickly proved sobering. Burdened by heavy packs, poorly organized supply wagons, and limited discipline, McDowell’s army moved slowly through the Virginia countryside. Heat exhaustion and logistical confusion plagued the advance. What was meant to be a rapid strike toward Confederate lines instead became a sluggish and uneven push, allowing Southern forces time to reinforce their positions.

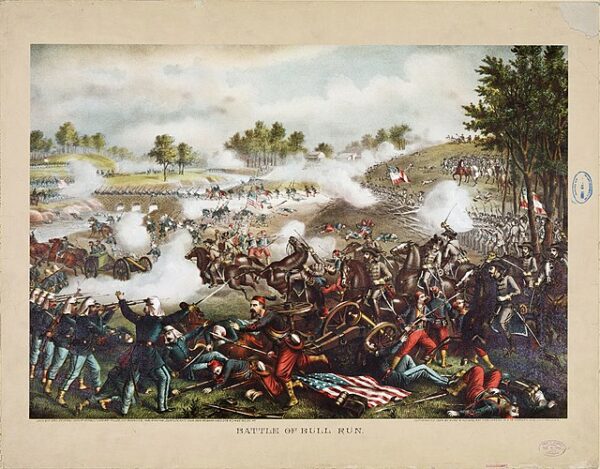

Unbeknownst to McDowell, Confederate leaders had already begun coordinating a defensive stand. General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding additional Confederate troops in the Shenandoah Valley, began moving his forces by rail toward Beauregard’s position—one of the first strategic uses of railroads in modern warfare. When battle was finally joined on July 21 near Bull Run Creek, the Confederates would outmaneuver the Union forces in a chaotic clash that ended in a disastrous Federal retreat.

Still, on July 16, none of this was certain. In Washington, excitement ran high. Spectators—including politicians, civilians, and even members of Congress—planned to travel south to watch what many assumed would be a decisive Union victory. Newspapers framed the campaign as a march to restore the Union in one bold stroke.

Lincoln himself had mixed feelings. Though he approved the operation, he understood the risks of fighting with unseasoned troops. Privately, he worried about the army’s readiness and the political fallout of a misstep. Yet he also recognized that continued inaction might cost the Union more in morale than any defeat could.

The First Battle of Bull Run would ultimately prove a turning point—not in territory gained or lost, but in perception. It demolished the North’s romantic notions of war, signaled the Confederacy’s tenacity, and inaugurated a brutal conflict that would last four years and claim over 600,000 lives. For the men who marched on July 16, it was the beginning of something far more terrible and enduring than they had imagined.