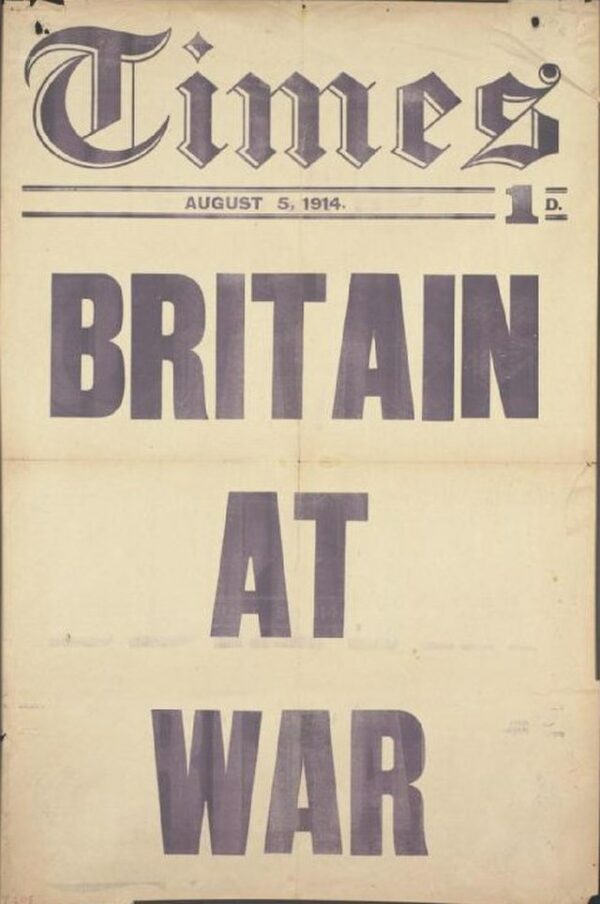

On August 4, 1914, the contours of what would become the First World War changed dramatically as three pivotal nations made their positions unmistakably clear. In response to Germany’s invasion of neutral Belgium, both Belgium and the British Empire formally declared war on the German Empire. On the same day, the United States, under President Woodrow Wilson, issued a proclamation of neutrality—signaling a desire to remain apart from what many in America saw as a distant European conflict.

The British declaration of war was triggered by the violation of Belgian neutrality. For nearly a century, Belgium had been protected under the Treaty of London (1839), in which Britain and other European powers had guaranteed its neutrality in the event of conflict. Germany’s decision to invade Belgium as part of the Schlieffen Plan—a military strategy aimed at quickly defeating France by sweeping through Belgium—presented London with a stark choice: abandon its treaty obligations or stand by its commitment to international law.

Germany had issued an ultimatum to Belgium on August 2, demanding free passage through its territory. King Albert I of Belgium rejected the ultimatum, stating that to comply would be to sacrifice the nation’s sovereignty. In the early hours of August 4, German troops crossed the Belgian border. That same day, the British government issued an ultimatum of its own to Germany, demanding withdrawal from Belgium by midnight, London time. When Germany failed to respond, Britain declared war just hours later.

The invasion of Belgium transformed the political and emotional climate in Britain. Until then, public opinion was divided over whether to intervene in the escalating continental war. But the breach of Belgian neutrality, accompanied by reports of German atrocities—some exaggerated, others real—galvanized support for action. Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey famously remarked, as the lamps were being extinguished in Whitehall that evening, “The lamps are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.”

Belgium, for its part, declared war in direct response to the invasion of its territory, calling up reserves and attempting to mount a defense against the vastly superior German army. Though Belgian forces would ultimately be overwhelmed, their spirited resistance delayed the German advance and disrupted the broader timetable of the Schlieffen Plan—a development with lasting consequences on the war’s trajectory.

Across the Atlantic, the United States adopted a markedly different course. President Woodrow Wilson issued a proclamation of neutrality, urging Americans to remain “impartial in thought as well as in action.” The vast majority of Americans supported the move. The United States had no formal alliances with European powers, and many citizens—especially those of German and Irish descent—had little sympathy for Britain or France. Moreover, Wilson’s decision reflected a broader belief in American exceptionalism: that the U.S. should stand apart from European entanglements and serve as a beacon of peace and moral clarity.

However, while neutrality was the official policy, the economic and cultural realities were more complex. American banks and businesses soon began extending credit and selling supplies to the Allied powers, particularly Britain and France, laying the groundwork for deeper involvement. The U.S. stance would come under increasing pressure in the years to follow, as German U-boat attacks on American and Allied shipping and the infamous Zimmermann Telegram would test the nation’s commitment to neutrality.

The events of August 4, 1914, mark a critical inflection point in world history. What began weeks earlier as a regional crisis following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand had, in the space of days, expanded into a general European war. Britain’s entry ensured that the conflict would extend far beyond the continent, involving its vast imperial holdings. Belgium’s defiance became a symbol of resistance and martyrdom. And the United States’ declaration of neutrality set the stage for its later transformation—from aloof observer to decisive participant in what would come to be known as the Great War.