On August 28, 1879, British troops finally closed in on the fugitive monarch who had so recently commanded the fearsome Zulu army. King Cetshwayo kaMpande, last sovereign of an independent Zulu nation, was captured in the aftermath of one of the most brutal colonial wars of the Victorian age. His seizure marked not only the end of the Anglo-Zulu War but also the eclipse of Zulu independence, a fate sealed less by battlefield defeat alone than by the imperial logic of partition and subjugation.

The Anglo-Zulu War had begun in January 1879 under the designs of Sir Henry Bartle Frere, the British high commissioner in southern Africa. Determined to create a confederation of colonies and client states under London’s authority, Frere viewed the Zulu kingdom as an impediment. Cetshwayo’s disciplined army—an estimated 40,000 strong, drilled under the regimental system devised by Shaka half a century earlier—stood as the last formidable indigenous power between the British settler frontier and continental hegemony. Presented with an ultimatum he could not possibly accept without dismantling his sovereignty, Cetshwayo braced for invasion.

The war opened with disaster for Britain. At Isandlwana in January, Zulu impis annihilated a British column, killing over 1,300 imperial troops in a single day—the worst defeat inflicted by an indigenous African army on the British Empire. Yet the victory could not be strategically consolidated. Cetshwayo forbade a direct assault on fortified positions, wary of losing his best warriors in suicidal attacks. The caution that had preserved his kingdom against African rivals now limited his ability to press advantage against a modern power willing to pour men, rifles, and artillery into the theater.

By July, after a grinding campaign of raids, skirmishes, and scorched earth, the war reached its climax at Ulundi. Lord Chelmsford, whose reputation had been shattered at Isandlwana, sought redemption in a decisive battle. His army, numbering 17,000 with artillery and Gatling guns, formed an impregnable square against which Cetshwayo’s 20,000 warriors hurled themselves. The result was slaughter. In less than an hour, the Zulu host was broken, and the royal kraal at Ulundi was set ablaze. The kingdom’s military power was crushed.

In the weeks that followed, Cetshwayo became a fugitive. Hounded by colonial patrols and betrayed by shifting allegiances among chiefs, he retreated northward, seeking to rally what remained of his followers. The British, eager to secure his person as a symbol of victory, dispatched mounted columns deep into Zululand. On August 28, Major Marter and Captain Barrow’s men surprised the king near the Black Mfolozi River. Accounts describe Cetshwayo as dignified in defeat, surrendering without resistance. He was conveyed to Cape Town, a prisoner of empire.

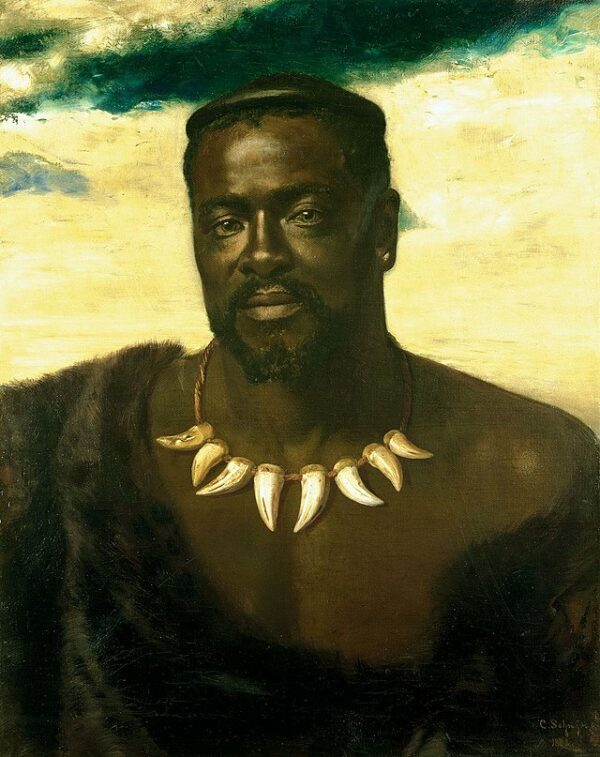

For the British, the capture was more than a tactical success; it was political theater. The Zulu kingdom was partitioned into thirteen chieftaincies under pro-British rulers, deliberately weakening the centralized authority that had once made it formidable. Cetshwayo himself, after years of confinement, was allowed to travel to London in 1882, where he was received with a curious blend of sympathy and condescension. He impressed Queen Victoria and the British public, who saw in him a noble if tragic figure—a king brought down by the inexorable advance of civilization. He was even restored to a reduced portion of his kingdom the following year, but internecine conflict and the continuing encroachments of colonists ensured that real sovereignty was never regained.

Cetshwayo’s downfall illustrates the larger pattern of nineteenth-century imperialism: indigenous powers could win stunning victories and field disciplined armies, yet the relentless material superiority of industrial empires—reinforced by political manipulation and divide-and-rule tactics—proved decisive. The Zulu king’s capture on that August day thus symbolized both the end of an epoch of African independence and the beginning of a new, harsher era in which native rulers would be cast as subjects of the empire rather than sovereign adversaries.

The Anglo-Zulu War remains etched in memory less for its ultimate outcome than for the drama of its battles: the stunning triumph at Isandlwana, the heroic defense of Rorke’s Drift, and the cataclysm at Ulundi. Yet behind those episodes lies the story of a monarch whose authority embodied the last flowering of Zulu statehood. Cetshwayo’s capture did not merely extinguish his reign; it extinguished the hope that the Zulu kingdom could stand as an equal in a world increasingly ordered by European empires.