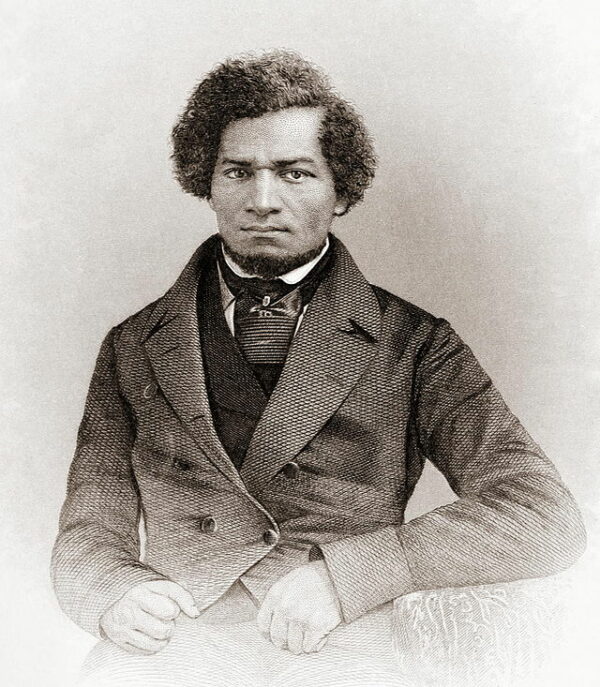

On September 3, 1838, a twenty-year-old enslaved man named Frederick Bailey (later Frederick Douglass) made his bid for freedom. His escape from bondage, carried out with quiet audacity on the railroads and waterways of the Mid-Atlantic, would alter not only the course of his life but also the trajectory of American abolitionism.

Born into slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in 1818, Douglass had already endured the brutality of the system that denied him personhood. He had been hired out to shipyards in Baltimore, where he learned the trade of caulking ships, and had suffered under the infamous “slave-breaker” Edward Covey. Yet those experiences also gave him skills, wages, and contacts in the city. By the late 1830s he was determined that bondage could no longer be his fate.

The plan for escape hinged on disguise and deception. Douglass borrowed the identification papers of a free Black sailor—documents that described their bearer as having dark skin, while Douglass himself was lighter in complexion. He donned a red shirt, tarpaulin hat, and sailor’s scarf, assuming the guise of a seaman moving through the busy corridors of transportation. In an age when Black travelers without papers risked immediate arrest, his borrowed pass was both a shield and a gamble. “On the morning of the third of September, 1838,” he later recalled, “I bade farewell to the city of Baltimore, and to that slavery which had been my abhorrence from childhood.”

The journey northward was fraught with peril. He first boarded a train bound for Havre de Grace, nervously handing over his sailor’s papers to a conductor. From there he transferred to a steamboat across the Susquehanna River, then resumed travel by rail and boat through Delaware and into Pennsylvania. Each stage of the trip carried the risk of exposure. A suspicious glance, a probing question, or the recognition of his face could have ended the attempt in chains. Yet fortune held. Within twenty-four hours Douglass had crossed into Philadelphia, a city where slavery had been abolished decades earlier. “I found myself in the midst of thousands of friends,” he wrote, “and in a land of freedom.”

From Philadelphia he continued on to New York City, arriving on September 4. Though free by law, Douglass was still vulnerable to capture under federal statutes and to slave catchers eager for reward. In the teeming, dangerous streets of Manhattan, he sought assistance from the abolitionist David Ruggles, leader of the New York Committee of Vigilance. Ruggles sheltered him, counseled him, and eventually arranged his safe passage to New Bedford, Massachusetts. There, Douglass reunited with Anna Murray, a free Black woman from Baltimore who had helped fund his escape. They married shortly after his arrival.

It was in New Bedford that Frederick Bailey took a new name: Frederick Douglass, inspired by a character in Sir Walter Scott’s poetry. In adopting this name, he signaled both a break with the past and a commitment to a new life as a free man. Work as a laborer in the whaling town sustained him, but it was his eloquence that soon distinguished him. Local abolitionists invited him to speak, and his oratory—rooted in the authenticity of his bondage and the brilliance of his mind—catapulted him to prominence.

The escape of September 3, 1838, thus stands not only as a personal liberation but as a symbolic act in the broader struggle against slavery. Douglass would go on to become one of the nineteenth century’s towering figures: an abolitionist, orator, journalist, and statesman whose very existence refuted the ideology of white supremacy. He published his first autobiography in 1845, electrifying readers with the firsthand testimony of slavery’s cruelties, and spent the following decades rallying the conscience of the nation toward emancipation.

In remembering that morning in Baltimore, Douglass often acknowledged the blend of fear and hope that defined the moment. He had no certainty of success—only the conviction that freedom was worth the risk. His successful escape on September 3, 1838, became the foundation of a life dedicated to ensuring that others might one day share in that same liberty.