On September 17, 1862, the rolling fields and cornrows along Antietam Creek bore witness to the single bloodiest day in American military history. George B. McClellan’s Union Army of the Potomac and Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia clashed in a desperate struggle that left more than 22,000 men dead, wounded, or missing by nightfall. The battle marked the climax of Lee’s first invasion of the North and proved a turning point in the Civil War, though not the decisive blow President Abraham Lincoln hoped for.

Lee had crossed the Potomac in early September, emboldened by victories at the Seven Days and Second Manassas. He believed a strike into Maryland could relieve war-torn Virginia, inspire Confederate sympathizers in the border states, and perhaps even draw European recognition of Southern independence. Yet his army was thin, numbering barely 40,000, and divided by long marches. McClellan, restored to command after his earlier failures, moved cautiously but finally advanced with more than 75,000 men to intercept the invaders.

The collision came at dawn near Sharpsburg. Union forces under Joseph Hooker surged across the Cornfield, their volleys mowing down ranks of Confederates under Stonewall Jackson. The ground shifted hands repeatedly, stalks shredded by musket fire until the field itself seemed alive with death. By midmorning, the Union had gained little beyond heaps of casualties.

To the south, another slaughter unfolded at the Sunken Road, soon known as “Bloody Lane.” Here, Confederates crouched behind a natural trench as Union columns advanced. For hours the road became a charnel house. Finally, pressure on the flanks broke the Southern line, leaving the lane clogged with bodies three deep. McClellan, however, failed to exploit the breach, holding back reserves that might have crushed Lee’s center.

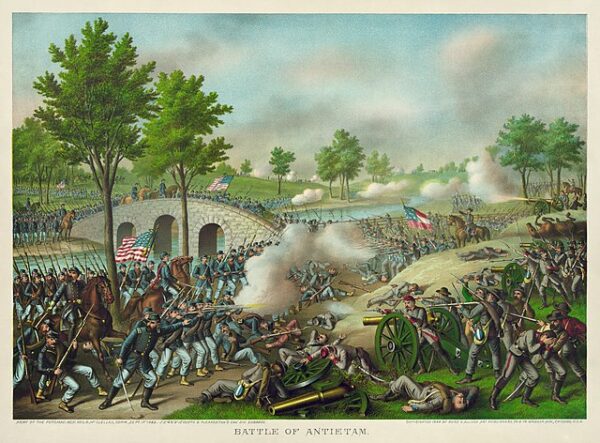

The final act came at Burnside’s Bridge. Union troops under Ambrose Burnside spent precious hours attempting to storm a narrow crossing over Antietam Creek, where a handful of Georgians held them at bay. When the bridge finally fell, Lee rushed reinforcements — including the division of A.P. Hill, arriving after a forced march from Harpers Ferry. Their counterattack drove Burnside back, preserving the Confederate position as dusk descended.

The scale of the carnage stunned the nation. Nearly 3,700 men lay dead, and more than 18,000 wounded filled barns, churches, and farmhouses for miles around. Families searched through rows of corpses, and photographers like Alexander Gardner captured grim images that brought the war’s horrors into Northern parlors. Antietam revealed the Civil War as a conflict of industrial slaughter, not gallant maneuver.

Militarily, the battle ended in stalemate. Lee, battered and outnumbered, held his ground on the 17th but slipped back across the Potomac two nights later. McClellan, true to form, failed to pursue vigorously, allowing the Confederate army to escape largely intact. His caution would cost him Lincoln’s confidence and ultimately his command. Yet strategically, the Union claimed a vital if incomplete victory: Lee’s first invasion of the North had been repelled.

The political consequences were immense. With Confederate arms checked on Union soil, Lincoln seized the moment to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. On September 22, just five days after the battle, he announced that enslaved people in rebel-held territory would be declared free on January 1. The proclamation transformed the Union war aim from merely preserving the nation to destroying slavery, reshaping international opinion and ensuring Britain and France would not recognize the Confederacy.

For the soldiers who fought at Antietam, the day remained etched in memory as the height of slaughter. Veterans spoke of the Cornfield as “more bloody than Gettysburg,” of the Sunken Road as a vision of hell, of the bridge where the creek ran red. Antietam became a byword for sacrifice, a place where courage met catastrophe, and where the course of the war shifted, however imperfectly, toward Union advantage.

The battle did not end the conflict, nor break Lee’s army, but it halted his bold gamble of 1862. On that September day, amid smoke and thunder, the Union held the line. In the silence that followed, America confronted the terrible price of civil war.