On January 7, 49 BC, the Roman Republic crossed a point of no return—not with the tramp of legions or the clash of steel, but with a decree of the Senate and the flight of two frightened magistrates. What followed would soon culminate in civil war and the end of republican government, but the Republic’s collapse began quietly, through legal absolutism, factional fear, and a final refusal to compromise.

At the center of the crisis stood Julius Caesar, then stationed at Ravenna at the northern edge of Italy. For nearly a decade, Caesar had commanded Rome’s armies in Gaul, delivering spectacular victories that enriched the state and transformed him into the most popular man in Roman public life. That success, however, made him intolerable to the Senate’s conservative elite. Rome’s political system had never been designed to absorb a figure of such concentrated military prestige without breaking.

The legal question appeared simple. Caesar’s proconsular command was nearing its end. Senate leaders demanded that he disband his army and return to Rome as a private citizen. Caesar countered with a proposal rooted firmly in precedent: he would relinquish his command if his rival Pompey the Great did the same. Both men, after all, held extraordinary military authority. The Senate rejected the offer outright. The issue was no longer legality—it was power.

In early January, the Senate issued an ultimatum. Caesar must disband his legions by a fixed deadline or be declared a hostis publicus—a public enemy of the Roman people. Such a declaration would strip him of legal protection and authorize armed force against him. It was a sentence disguised as procedure. Compliance meant political annihilation; refusal meant civil war.

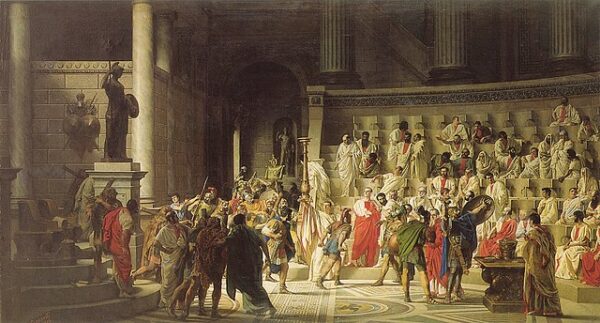

Two tribunes of the plebs attempted to intervene. The tribunate existed precisely for moments like this—when aristocratic power threatened to override popular rights. Invoking their constitutional authority, the tribunes vetoed the Senate’s decree, arguing that it violated both custom and law. In an earlier Republic, that veto would have ended the matter.

Instead, the Senate ignored it.

Threatened with arrest and physical harm, the tribunes fled Rome under cover of night. Disguised and desperate, they made their way north to Ravenna, where Caesar awaited developments. Their arrival on January 7 transformed a political crisis into a constitutional catastrophe. Tribunes were legally sacrosanct; to intimidate them for exercising their office was not merely illegal—it was revolutionary.

The symbolism was unmistakable. The guardians of popular liberty were now refugees in a general’s camp. The Senate, claiming to defend the Republic, had abandoned its own constitutional restraints. Caesar, long accused of authoritarian ambition, could now plausibly argue that the Republic’s laws had already been broken—by his enemies.

Rome’s political order had been eroding for years. Emergency powers had become routine. Elections were openly bought. Violence increasingly substituted for persuasion. Figures like Pompey had normalized extraordinary commands while insisting that only Caesar posed a threat to liberty. By 49 BC, legality had become a weapon wielded selectively, not a shared framework respected by all.

When Caesar received the Senate’s decree and the fleeing tribunes on January 7, the choice before him was stark. To disband his army was to submit to prosecution and humiliation at the hands of men determined to destroy him. To advance into Italy under arms was treason. The Republic had engineered a dilemma in which obedience and rebellion were indistinguishable.

Within days, Caesar would march south and cross the Rubicon, initiating a civil war that would end with dictatorship and, ultimately, empire. Yet the decisive rupture had already occurred. It happened when the Senate chose coercion over compromise, when constitutional vetoes were brushed aside, and when Rome’s elected tribunes fled for their lives.

On January 7, 49 BC, the Republic still existed in name, but it was already lost.