In the bleak aftermath of the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Union Army stood stunned—not merely by defeat, but by the scale and clarity of it. On January 26, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln formally relieved Ambrose Burnside of command of the Army of the Potomac, ending one of the shortest and most ill-fated tenures in Civil War history. In his place, Lincoln turned—once again, and with evident reluctance—to Joseph Hooker, a talented but controversial officer whose reputation for ambition nearly matched his record on the battlefield.

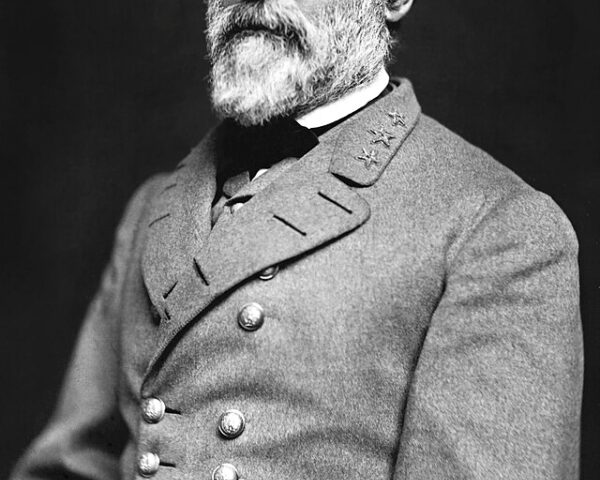

The decision followed the catastrophe at Fredericksburg, where Burnside’s December 1862 offensive collapsed into slaughter. Facing Robert E. Lee’s entrenched Confederate army on the heights west of town, Burnside ordered repeated frontal assaults across open ground—attacks that were repulsed with horrifying efficiency. Union casualties exceeded 12,000 in a single day; Confederate losses were a fraction of that number. The lopsided result was not merely a tactical failure but a moral blow to the North, one that reverberated through newspapers, Congress, and the White House itself.

Burnside, by temperament and inclination, was an unlikely savior for the Union cause. He had accepted command reluctantly, only after twice declining it and only when Lincoln—desperate after George McClellan’s removal—pressed the issue. Burnside was honest, loyal, and personally brave, but he lacked the strategic imagination and political deftness the role demanded. Fredericksburg exposed these limitations in merciless detail. Worse still, his subsequent attempt to redeem himself—the infamous “Mud March” of January 1863—collapsed into farce as rain turned Virginia roads into impassable swamps, immobilizing men and artillery alike.

By mid-January, confidence in Burnside had evaporated. Senior officers openly criticized him; rumors of resignations and intrigue circulated freely within the army’s winter camps. Burnside himself, increasingly isolated, proposed a sweeping purge of his subordinates—an extraordinary request that would have sidelined several high-ranking generals. Lincoln, already wary, refused. The president had reached a familiar conclusion: the problem was not merely the generals around Burnside. It was Burnside.

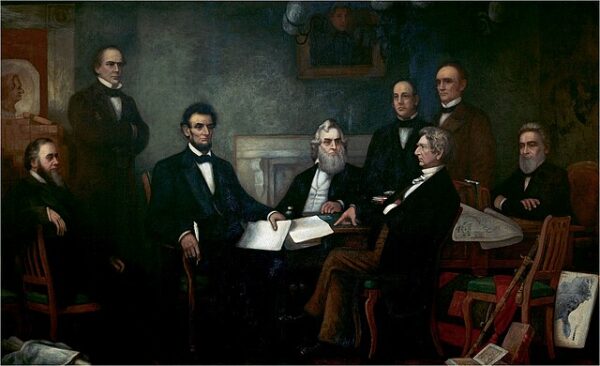

Lincoln’s choice of Joseph Hooker reflected both necessity and risk. Hooker was aggressive, intellectually sharp, and widely admired by the rank and file. He had a keen eye for logistics and morale and immediately set about reforming the army—improving rations, sanitation, pay systems, and discipline. Yet Hooker also carried baggage. He had been openly critical of his superiors and had gained a reputation, fair or not, for political scheming and personal excess. Lincoln knew this. In a now-famous letter, the president warned Hooker against ambition and insubordination, cautioning that “the spirit which you have aided to infuse into the army… is one of criticizing their commander.”

Still, Lincoln gambled. The Army of the Potomac, battered and demoralized, required not caution but revival. Burnside’s removal was an admission of failure, but also a recognition of urgency. The war was entering its third year. Emancipation had just been proclaimed. The Union could no longer afford commanders who merely endured. It needed generals who could act.

History would judge the transition with mixed results. Hooker would restore the army’s confidence and efficiency, but his own reckoning would come at Chancellorsville a few months later. Burnside, reassigned to other duties, would never again command the Army of the Potomac. Yet January 26, 1863, marked more than a change in leadership. It underscored a grim truth of the Civil War: victory would demand not only men and materiel, but a relentless search—often painful, often public—for the right command at the right moment.