On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther, a young theology professor, took a daring step that would ignite the Protestant Reformation, reshaping both Christianity and European society. Luther, an Augustinian monk and scholar at the University of Wittenberg in Saxony, was increasingly troubled by certain practices within the Catholic Church, especially the sale of indulgences. These indulgences were sold as a means to “buy” forgiveness, promising reduced time in purgatory in exchange for financial contributions—a concept that Luther found both morally and theologically troubling. The church marketed indulgences as a means to secure salvation for oneself or loved ones, fueling a highly profitable campaign driven by popular preachers like Johann Tetzel. Tetzel, a Dominican friar, aggressively promoted indulgences, appealing to the fears and emotions of the faithful, with the funds largely supporting the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Through his study of scripture, particularly Paul’s letters, Luther grew convinced that salvation was not something one could buy or earn but was a gift given solely through faith. This principle, sola fide (faith alone), became the cornerstone of his reformist message. In his 95 Theses, formally titled Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences, Luther presented his arguments, urging a return to a simpler, scripture-centered faith. Each thesis critiqued church policies, yet Luther’s intent was not to sever ties with Catholicism but to spark an academic debate on reform.

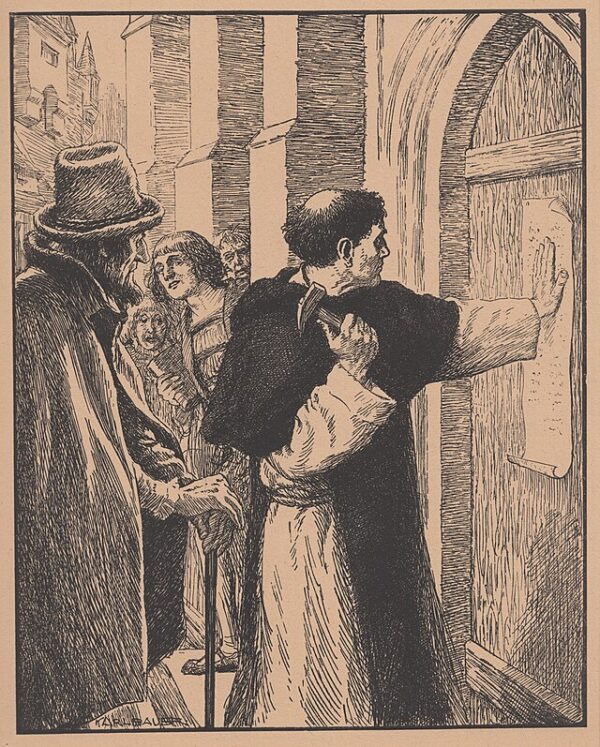

On the eve of All Saints’ Day, Luther is said to have nailed his 95 Theses to the door of Wittenberg’s Castle Church, although some historians believe he may have initially sent copies to church leaders instead. At the time, posting such notices was a common way for scholars to initiate discussions. However, Luther’s message quickly transcended academic circles, resonating widely thanks to the newly invented printing press. This technology allowed the 95 Theses to spread rapidly across Europe, translated into German to reach the lay public, where it struck a powerful chord, particularly in regions where resentment toward the Catholic Church’s power and wealth was already simmering.

Luther’s challenge met with both enthusiastic support and vehement opposition. Pope Leo X initially dismissed Luther’s objections as the trivial complaints of a monk, but as Luther’s ideas gained momentum, church authorities grew alarmed. Summoned to Rome to recant, Luther instead held his ground, arguing that the Bible’s authority superseded that of the pope. His refusal ultimately led to his excommunication in 1521, and he was declared an outlaw after refusing to retract his views at the Diet of Worms.

This bold stand marked a turning point that would inspire profound change. Luther’s 95 Theses catalyzed the formation of new Protestant denominations, including Lutheranism and Calvinism. His ideas also resonated beyond the church, encouraging people to question authority and seek individual freedom. Luther’s translation of the Bible into German empowered ordinary people to read and interpret scripture for themselves, promoting literacy and shifting religious authority from clergy to laity.

The Reformation brought significant political consequences, too. Across Europe, rulers saw Protestantism as an opportunity to challenge papal authority and strengthen their own power. In Germany, Luther’s influence sparked conflicts between Protestant-leaning princes and those loyal to Catholicism, eventually culminating in the Thirty Years’ War. The legacy of Luther’s actions on October 31, 1517, remains a defining moment in history, transforming the spiritual, social, and political fabric of Western society. Whether Luther’s hammer strokes on the Wittenberg church door were literal or symbolic, their reverberations reshaped Christianity and laid a foundation for modern religious thought.