On December 25, 800 AD, in the grand Basilica of St. Peter in Rome, Charlemagne, the King of the Franks, was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III. This pivotal event not only reshaped European history but also established the political and cultural foundations of medieval Europe. By the late 8th century, Charlemagne had already earned a reputation as a powerful and effective leader. Through military conquests and administrative reforms, he unified large portions of Western Europe, encompassing modern-day France, Germany, Belgium, and parts of Italy. His leadership brought much-needed stability to a region still fragmented after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD.

The circumstances leading to Charlemagne’s coronation were closely tied to the political struggles of the papacy. Pope Leo III faced fierce opposition from the Roman nobility, who sought to undermine his authority. In 799, Leo was attacked and mutilated by his adversaries but managed to escape and seek refuge in Charlemagne’s court. Charlemagne not only offered him protection but also restored him to power in Rome. This act solidified their alliance and emphasized Charlemagne’s growing influence over the papacy.

On Christmas Day in 800 AD, during a solemn mass at St. Peter’s Basilica, Pope Leo III placed a golden crown on Charlemagne’s head and declared him “Emperor of the Romans.” While contemporary accounts suggest Charlemagne was taken by surprise, modern historians debate whether he was truly unaware of the pope’s intentions. The coronation symbolized the blending of Roman, Christian, and Germanic traditions, forming a new political entity: the Holy Roman Empire. The title of Emperor carried immense weight, linking Charlemagne’s rule to the prestigious legacy of ancient Rome. It positioned him not merely as a king but as a sovereign chosen by God to lead and protect Christendom. This coronation reinforced the concept of a unified Christian Europe under both spiritual and temporal leadership, merging religious and political authority.

The crowning of Charlemagne created significant political tensions, particularly with the Byzantine Empire, which considered itself the legitimate successor of the Roman Empire. To Byzantine rulers, Charlemagne’s new title was seen as a direct challenge to their sovereignty. This rivalry contributed to the growing divide between the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Western Catholic Church, a split that would eventually culminate in the Great Schism of 1054.

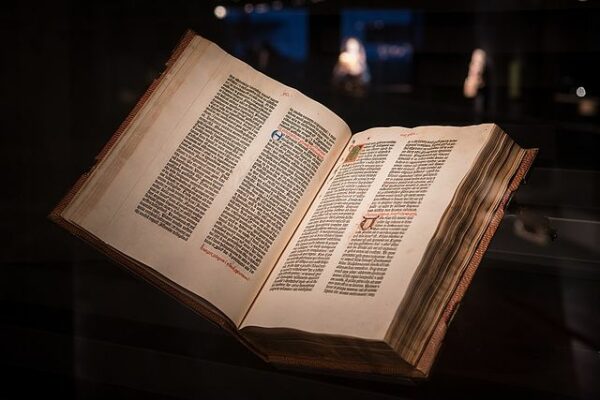

Following his coronation, Charlemagne continued to implement transformative reforms, ushering in an era often referred to as the Carolingian Renaissance. He promoted education, encouraged the preservation of ancient manuscripts, and established monastic and cathedral schools across his empire. His governance reforms improved administrative efficiency, military organization, and economic stability, laying the groundwork for future European states.

Charlemagne’s coronation set a powerful precedent for future European monarchs. The idea of divine kingship, where rulers were perceived as being appointed by God, became a cornerstone of medieval political philosophy. The Holy Roman Empire, despite evolving significantly over time, remained a dominant political institution in Europe for nearly a thousand years.