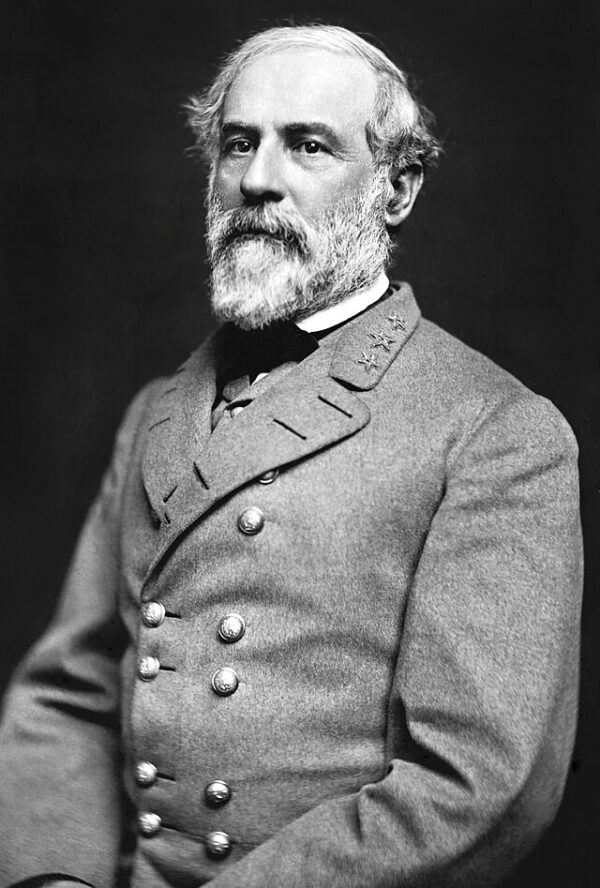

On January 31, 1865, Robert E. Lee was appointed general-in-chief of all Confederate armies, a decision that came during the final, desperate months of the American Civil War. By this point, the Confederacy was struggling against relentless Union advances, and its military situation was deteriorating rapidly. Confederate President Jefferson Davis hoped that placing Lee in overall command might shift the course of the war, given his reputation as the South’s most capable general. However, the Confederacy was already on the brink of collapse, and even Lee’s leadership could not reverse its fortunes.

Lee had long been recognized as the Confederacy’s most successful military commander, leading the Army of Northern Virginia through several major victories. Since assuming command in June 1862, he had secured triumphs at battles such as Second Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville, often outmaneuvering Union generals. His reputation as a brilliant strategist made him a symbol of Southern resistance. However, the war’s momentum began to shift against him following the devastating Confederate loss at Gettysburg in July 1863. As Union forces continued to grow in strength, Lee’s army struggled with dwindling resources and mounting casualties.

The appointment of Ulysses S. Grant as the Union’s overall commander in March 1864 introduced a new strategy of relentless pressure. Grant engaged in a brutal war of attrition against Lee’s forces, leading to significant Confederate losses. By early 1865, the situation for the South was dire. Union armies had tightened their grip on Confederate territory, cutting supply lines and crippling the Southern war effort. The Confederate Congress created the position of general-in-chief in a last attempt to centralize military leadership, and Lee was officially appointed to the role on January 31.

Upon assuming command, Lee faced overwhelming challenges. The Confederacy lacked soldiers, supplies, and morale. Union forces were closing in on key Southern cities, with Grant’s army besieging Petersburg and Sherman’s forces devastating the Deep South. Recognizing the Confederacy’s dire circumstances, Lee urged the government to take extreme measures, including enlisting enslaved men as soldiers in exchange for their freedom. However, this policy was approved too late to have any real impact on the war’s outcome.

As Union forces intensified their attacks, Lee’s army was forced into retreat. By early April, Grant’s troops had finally broken through at Petersburg, leading to the fall of Richmond, the Confederate capital. Lee attempted to escape westward, hoping to regroup, but his army was too weakened to continue fighting. On April 9, just over two months after becoming general-in-chief, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House. His surrender effectively marked the end of the Civil War in Virginia, and within weeks, the remaining Confederate armies laid down their arms.

Lee’s appointment as general-in-chief was a desperate move by the Confederacy, made too late to make any meaningful change to the course of the war. His legacy remains deeply controversial—some see him as a brilliant tactician who fought for his home state, while others view him as a symbol of Confederate treason and its defense of slavery.