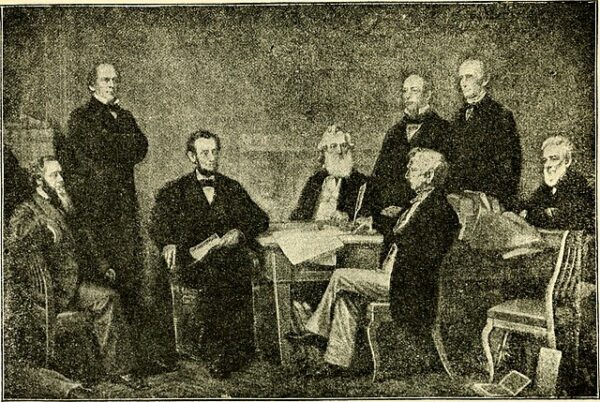

On April 15, 1861, just two days after Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 militia troops. His goal was to put down what he described as an uprising too strong to be handled by the courts. While his message used careful legal language, the consequences were anything but mild—it marked the moment when the United States slid irreversibly into civil war.

This proclamation came after Fort Sumter’s surrender, giving Lincoln the justification he needed to act decisively. Up to that point, he had balanced cautious diplomacy with a firm stance on preserving the Union. By asking for troops, Lincoln made it clear that he rejected secession as a lawful option and was ready to defend the Union—even with force. This move drastically reduced the chances for compromise and forced the remaining undecided slave states, especially in the upper South, to pick a side.

Reactions were immediate and dramatic. In the North, Lincoln’s call ignited a wave of patriotism. Crowds filled city streets, flags flew, and volunteers quickly signed up for military service. Most people believed the conflict would be short, and many were motivated by a mix of idealism and practicality. But the South reacted just as strongly in the opposite direction. States like Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee—previously hesitant to join the Confederacy—now saw Lincoln’s move as an act of aggression and chose to secede.

Legally, Lincoln relied on the Militia Act of 1795, which allowed the president to call out state militias during rebellions. But his deeper reasoning was rooted in his belief about the nature of the Union. He didn’t see the United States as a loose agreement between states, but as a lasting nation created by its people. Allowing secession, he believed, would destroy the very principles of democratic government. So his call to arms wasn’t just about military action—it was a moral and constitutional stand to defend democracy itself.

From the Southern perspective, however, Lincoln’s move confirmed their worst fears. Confederate President Jefferson Davis had already begun organizing troops, and Lincoln’s proclamation was seen as evidence that the federal government intended to force the South into submission. Southern newspapers portrayed the call as the start of a war of aggression, uniting many Southerners behind the Confederate cause.

Looking back, Lincoln’s April 15 proclamation was the moment when political tensions turned into full-blown war. The earlier phases of the crisis—southern secession, the Fort Sumter standoff, and the uncertain position of border states—gave way to a stark choice: support the Union or the Confederacy. There was no longer any middle ground.

Lincoln’s decision also highlighted a central challenge in American democracy: sometimes, preserving a government based on the people’s will might require strong federal action. By demanding loyalty from rebellious states, he expanded federal power, even as he defended democratic principles. This paradox would shape not only his presidency but also the lasting constitutional changes brought by the Civil War.

Ultimately, April 15, 1861, was more than just the beginning of war—it was the point when the national debate over slavery, sovereignty, and the survival of the republic could no longer be settled through discussion. From that moment on, the Union would be preserved, if at all, by the determination of those who answered Lincoln’s call—not to conquer, but to save their country.