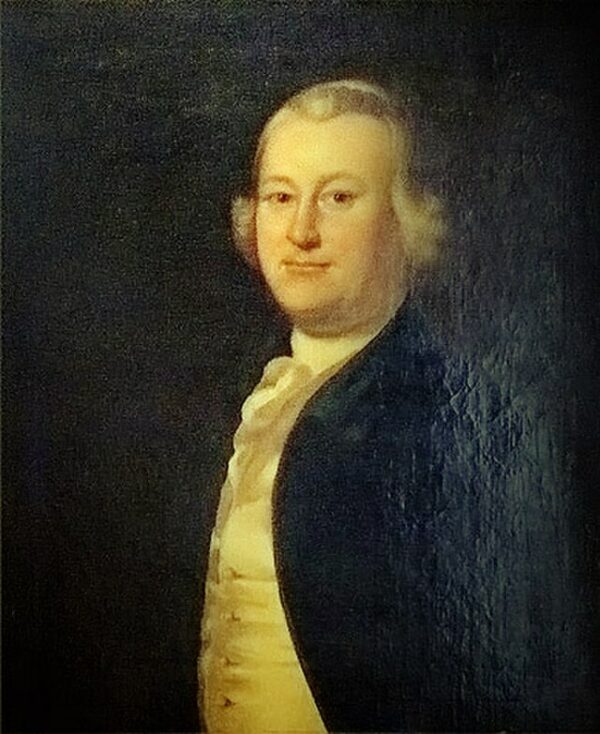

In a dramatic address that shook the walls of the Massachusetts General Court and reverberated across the Atlantic, James Otis Jr. on Tuesday, June 21, 1768, launched a sweeping denunciation of British authority—accusing Parliament of violating the Constitution and likening taxation without representation to political slavery.

Standing before a divided chamber in Boston, Otis—already a familiar name to British officials for his earlier legal challenges—declared that the Townshend Acts were “instruments of tyranny” and warned that Parliament’s powers were not absolute. “The power of Parliament is not infinite,” he said. “It is circumscribed by reason and justice, as are all the institutions of men.”

His speech, prompted by mounting unrest over import duties on glass, paper, paint, and tea, came as tensions between colonial merchants and royal customs agents neared a breaking point. British warships loomed in the harbor, and troops were rumored to be en route to Boston. But Otis showed no signs of restraint. Instead, he accused Parliament of stripping colonists of their English liberties and asserted that Americans were entitled to the same rights as subjects in Kent or Westminster.

Otis, whose 1761 courtroom attack on writs of assistance helped ignite colonial opposition to British surveillance, now turned his sights fully on Parliament itself. He did not call for independence—at least not yet—but he called into question the very premise of imperial authority over domestic colonial affairs. “The right to tax is the right to destroy,” he warned, a phrase that would echo in pamphlets and taverns across the colonies.

The response from royal officials was swift. Governor Francis Bernard reported the speech to London as “highly inflammatory,” and British loyalists accused Otis of inciting rebellion. Within weeks, the press in England condemned him as a dangerous radical. But in Boston, Otis’s oration landed differently—many colonists saw it as a long-overdue rebuke to imperial overreach. Town meetings and local assemblies would soon adopt the language of his protest in petitions to the Crown.

Otis’s allies praised him as a patriot willing to risk everything. His critics dismissed him as reckless and unstable. Both would soon be partly right. Though once regarded as one of the sharpest legal minds in the colonies, Otis’s later years would be marked by declining mental health and political isolation. But in 1768, his words carried weight far beyond Boston.

“He spoke with the voice of a continent,” one supporter wrote afterward.

Otis’s message was rooted in Enlightenment political theory—drawing heavily on the idea that government derives its authority from the consent of the governed. At a time when even moderate colonial leaders still pledged allegiance to the king, Otis framed British rule not as misguided, but illegitimate. “Government is a compact,” he said, “and when that compact is broken, the people have a right to resist.”

Though often overshadowed by later figures like Samuel Adams and John Hancock, Otis’s stand on June 21 helped lay the ideological foundation for the Revolution. In confronting Parliament head-on, he did more than voice dissent—he introduced the idea that obedience to unjust laws was not only unnecessary, but dishonorable.

Within a year, British troops would occupy Boston. Within seven, the colonies would be at war.

But on that day in 1768, with the galleries full and the city on edge, one voice rang out in defiance. James Otis Jr. had spoken. And Parliament had been warned.