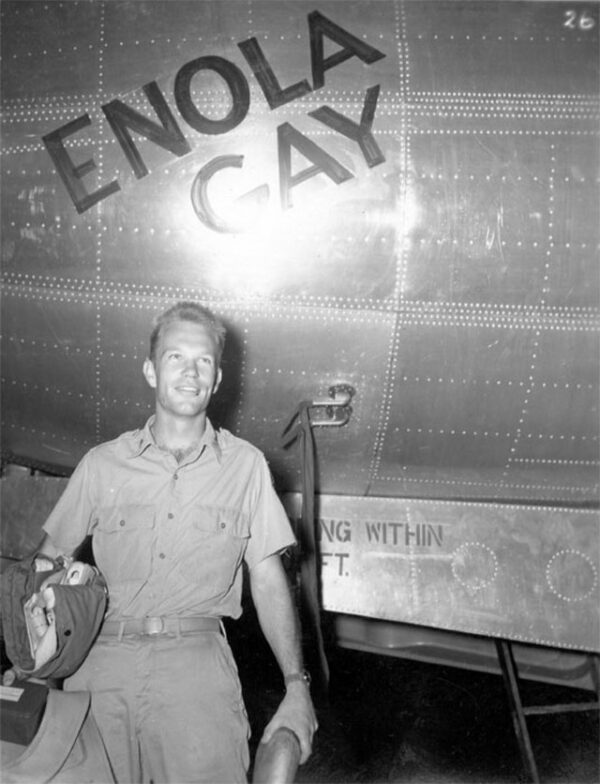

On the morning of August 6, 1945, a single American B-29 bomber—Enola Gay—emblazoned with the name of the pilot’s mother, took off from the island of Tinian in the western Pacific. Its mission, cloaked in secrecy and unprecedented in history, was to bring a swift and decisive end to the most devastating war the world had ever seen. At 8:15 a.m. local time, as the Japanese city of Hiroshima bustled below with workers, schoolchildren, and soldiers alike, the bomber released a single payload: a uranium-based atomic bomb code-named Little Boy. Forty-three seconds later, Hiroshima was engulfed in a blinding flash of light, followed by a fireball that vaporized everything within a one-mile radius. The atomic age had begun.

From an American perspective, the bombing of Hiroshima was the culmination of both scientific triumph and military desperation. The United States had spent billions of dollars under the top-secret Manhattan Project to develop atomic weapons before Nazi Germany could. By the time the bomb was ready for deployment, Germany had already surrendered. But Japan, though militarily defeated, refused to accept unconditional surrender. With the costly invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa fresh in memory—where American troops suffered staggering casualties—U.S. leaders feared a full-scale invasion of the Japanese home islands would result in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of American soldiers and perhaps millions of Japanese civilians.

President Harry S. Truman, who had taken office just months earlier after the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, faced one of the most consequential decisions in American history. After consulting with his military and civilian advisors, Truman authorized the use of atomic weapons to compel Japan’s surrender and save American lives. “It is an awful responsibility that has come to us,” Truman wrote in his diary on July 25, 1945. “We thank God that it has come to us, instead of to our enemies.”

Hiroshima, chosen for its military importance and untouched by previous large-scale bombing, was reduced to ashes in an instant. An estimated 70,000 people—men, women, and children—died immediately. Tens of thousands more would succumb in the days, weeks, and years to burns, wounds, and radiation sickness. Survivors, known as hibakusha, endured physical and psychological trauma for the rest of their lives, many becoming vocal advocates for peace and nuclear disarmament.

In the United States, the immediate public reaction to the bombing was largely supportive. For a war-weary nation still grappling with the loss of over 400,000 of its own sons and daughters, Hiroshima seemed to promise an end to the nightmare. Newspaper headlines declared the bombing a scientific marvel and a military victory. Americans, many of whom had family members serving in the Pacific theater, greeted the news with relief and even celebration.

Yet as the full scope of the devastation became known in the years that followed, a moral reckoning began to take root. Photographs of charred children and flattened neighborhoods stirred unease. The haunting legacy of radiation poisoning, and the realization that humanity now possessed the means to destroy itself in minutes, spurred intense debates across American society. Scientists who had built the bomb, including J. Robert Oppenheimer, began to question the consequences of their work. “In some sort of crude sense,” Oppenheimer later recalled, “the physicists have known sin.”

Still, from the American wartime perspective, the bombing of Hiroshima—and three days later, Nagasaki—achieved its intended purpose. On August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender. World War II was over.