When U.S. troops marched through the cobbled streets of San Juan on October 18, 1898, the red and gold flag of Spain was lowered for the last time over the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico. In its place rose the Stars and Stripes, signifying the transfer of sovereignty from one empire to another. The ceremony—formal, solemn, and quietly momentous—marked not only the end of more than four centuries of Spanish rule, but also the beginning of America’s transformation into a global power.

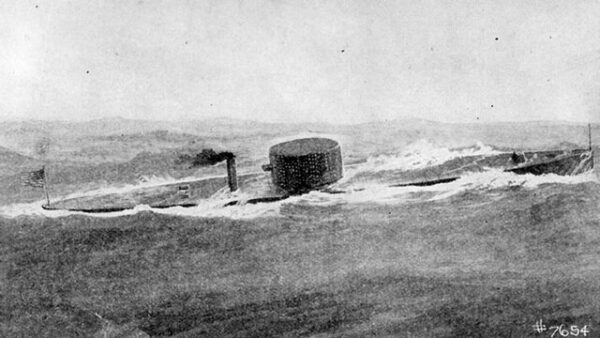

The event was the culmination of the Spanish-American War, a short but decisive conflict that reshaped the map of the Western Hemisphere. Following the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor in February 1898 and the U.S. declaration of war in April, American forces rapidly defeated Spain’s decaying imperial navy in both the Caribbean and the Pacific. The war’s outcome forced Spain to surrender its remaining colonies—Cuba, the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico—ending its centuries-long dominance in the Americas.

The U.S. invasion of Puerto Rico began on July 25, 1898, when General Nelson A. Miles landed at Guánica on the island’s southern coast. Miles declared that the American mission was one of “liberation, not conquest,” promising prosperity and protection under the new flag. The campaign was relatively brief and lightly contested. Many Puerto Ricans, weary of Spanish neglect and drawn by the prospect of reform, offered little resistance to the U.S. advance. By mid-August, with Spain seeking peace, the island was effectively under American control. The formal transfer, however, awaited the signing of the Treaty of Paris, which would conclude the war and codify U.S. claims.

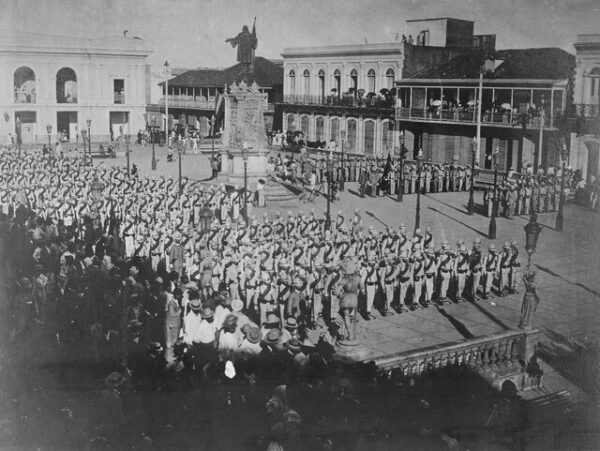

That transfer came on October 18. The ceremony unfolded at the Spanish governor’s palace in San Juan—La Fortaleza—where American and Spanish officials met to complete the handover. At precisely 11 a.m., as Spanish troops stood at attention, the Spanish flag was lowered to the sound of a bugle. Moments later, an American officer signaled, and the U.S. flag ascended the pole, greeted by the booming of artillery salutes from ships in the harbor. Observers noted that the Spanish soldiers watched in silence, their faces solemn; for many, it was the end of a 406-year chapter in the island’s history.

For the United States, Puerto Rico represented more than a trophy of war. Strategically located near the entrance to the Caribbean, it was seen as a valuable naval base and a gateway to trade routes in the Americas. The island also provided a symbolic foothold in America’s new “imperial moment”—a time when expansionists such as Theodore Roosevelt and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge argued that the U.S. must project power overseas to secure markets and influence. The annexation of Puerto Rico, along with the Philippines and Guam, reflected the nation’s turn toward global engagement after centuries of continental expansion.

For Puerto Ricans, however, the implications were complex. Initially, many hoped that U.S. rule would bring modernization, education, and greater political rights. But the Treaty of Paris, signed in December 1898, made no mention of independence. Instead, Puerto Rico became an “unincorporated territory” of the United States—subject to American sovereignty but without full constitutional protections. In the years that followed, Congress passed the Foraker Act of 1900, establishing a civil government under U.S. oversight, and the Jones-Shafroth Act of 1917, which granted U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans but withheld voting representation in Congress.

The October 18 handover thus stood at the crossroads of empire and identity. For Spain, it marked the twilight of its colonial grandeur. For the United States, it signaled the dawn of a new geopolitical role—one that blended republican ideals with imperial ambitions.