The winter of 627 opened with an army that should not have existed. After years of catastrophic defeats, territorial losses stretching from Egypt to Syria, and a Persian occupation that once reached the very gates of Constantinople, the Byzantine Empire was expected—by friends and enemies alike—to collapse. Instead, Heraclius, a once-unlikely emperor who inherited a treasury near empty and a capital in despair, marched into Mesopotamia at the head of a hardened, mobile strike force. On December 12, near the ruins of ancient Nineveh, he met the army of the Sassanian Empire in a battle that would decide the fate of the Near East.

The engagement unfolded against the larger backdrop of a war already two decades old, a conflict that had begun with Khosrau II’s claim that he sought vengeance for the murder of his Byzantine ally, Emperor Maurice. That justification had long since evaporated, replaced by something far more elemental: the competition of imperial wills, each determined to crush the other’s political and religious world order. Khosrau’s armies had conquered Jerusalem and seized the True Cross—an act that turned the conflict into a quasi-apocalyptic struggle for many within the Christian empire. Heraclius’s response, staged through a remarkable series of campaigns in Armenia and northern Mesopotamia, set the stage for the showdown in the plains near Nineveh.

The Persian commander Rhahzadh, entrusted with stopping the emperor’s advance, sought to force a rapid, conclusive clash. What he faced, however, was a Byzantine army transformed. Heraclius had restructured his forces into fast, flexible units capable of striking deep beyond the empire’s traditional defensive lines. On the morning of December 12, shrouded in thick fog that muffled sound and obscured distance, Heraclius deliberately initiated a feigned retreat—drawing the Persians into uneven terrain where the Byzantine cavalry could envelop their flanks.

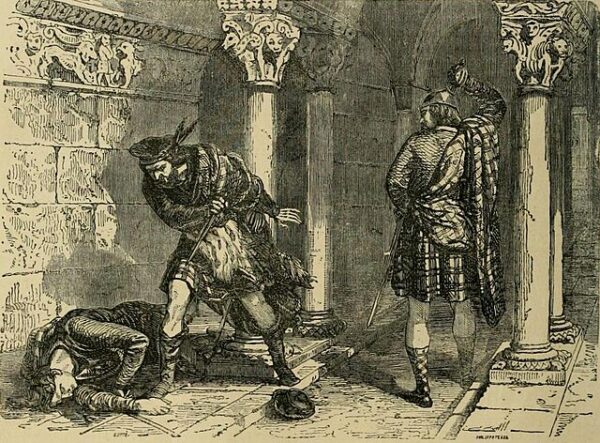

The battle soon fragmented into a series of brutal, close-quarters engagements. Contemporary accounts emphasize Heraclius’s physical presence in the fight: a commander who did not merely direct maneuvers from horseback but personally led charges, rallying men who had grown accustomed to retreat earlier in the war. By midday, the fog had lifted, revealing a field strewn with the shattered formations of Rhahzadh’s army. When the Persian general fell—killed in single combat with Heraclius, according to Byzantine chroniclers—the cohesion of his forces evaporated. The rout that followed was not merely a tactical collapse; it was the psychological unmaking of a military machine once considered the most formidable in the region.

The victory at Nineveh carried consequences that reached far beyond the battlefield. Heraclius immediately exploited the breach, pushing south toward the Persian heartland. Khosrau II, already facing noble unrest, found his legitimacy drained by defeat. Within months, he was overthrown and executed by his own son, who, desperate to stabilize a fracturing empire, sued for peace. The Treaty of 628 restored the Byzantine Empire’s lost territories and returned the relic of the True Cross—an outcome that contemporaries hailed as divine vindication.

Yet the triumph proved fleeting. Both empires emerged exhausted, impoverished, and politically hollowed out. What Heraclius achieved at Nineveh—arguably one of the most audacious military recoveries in imperial history—could not reverse the deeper structural damage inflicted by decades of war. Within a decade, the Arab armies of the Rashidun Caliphate would sweep across Syria, Iraq, Persia, and Egypt, conquering regions neither Byzantium nor the Sassanians had been able to defend or rebuild.

Still, Nineveh remains a hinge of history. It marked the moment when Heraclius seized back the initiative from a seemingly unstoppable rival, demonstrating how leadership, mobility, and tactical daring could rewrite the trajectory of a collapsing state. The Persian Empire would never fully recover; the Byzantine Empire, though momentarily resurgent, was already entering a new world whose contours had been shaped, in part, by what happened in the fog on December 12, 627.