On January 14, 1943, in the midst of a global war whose outcome was anything but assured, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill opened what would become one of the most consequential Allied strategy meetings of World War II: the Casablanca Conference. Convened in the Moroccan port city of Casablanca—then firmly under Allied control after Operation Torch—the conference marked a turning point in how the war would be fought, explained, and ultimately concluded.

The setting itself conveyed urgency and calculation. Held at the Anfa Hotel complex under heavy secrecy, the conference reflected the precarious balance of early 1943. The Allies had achieved critical successes in North Africa, pushing Axis forces toward defeat in Tunisia, yet the broader war remained unsettled. Nazi Germany still dominated much of Europe. The Soviet Union, bearing the brunt of the fighting on the Eastern Front, was locked in a titanic struggle for survival. Japan continued to expand and entrench its position across the Pacific. Victory was conceivable—but far from inevitable.

Roosevelt and Churchill arrived in Casablanca with overlapping goals and unresolved tensions. Both leaders agreed that the war required sustained cooperation between the Anglo-American powers, but they differed on how and where to strike next. American military planners, increasingly confident in U.S. industrial and manpower superiority, favored a direct cross-Channel invasion of France at the earliest possible moment. British leaders, shaped by the trauma of World War I and acutely aware of German defensive strength, argued for a more indirect approach—pressuring the Axis through the Mediterranean before attempting a full-scale assault on Western Europe.

The Casablanca Conference became the arena in which these competing visions were debated, refined, and partially reconciled. Over ten days of meetings, Roosevelt and Churchill—joined by senior military commanders—examined operations in North Africa, the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, and the Pacific. While Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was invited, he declined to attend, citing the ongoing Battle of Stalingrad. His absence, however, loomed large over the discussions, reinforcing Allied awareness that time and pressure mattered greatly on the Eastern Front.

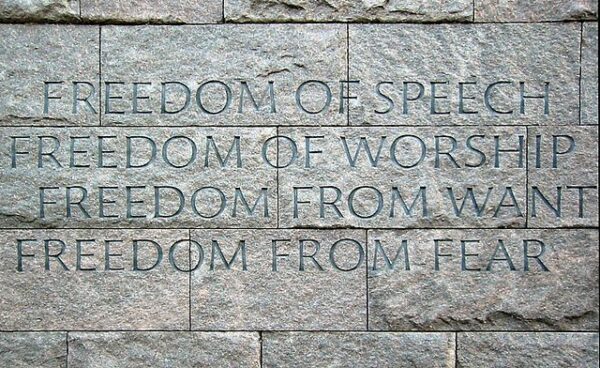

The most enduring legacy of Casablanca emerged not from a map table but from a press conference. On January 24, Roosevelt announced a policy that would define Allied war aims: the Axis powers would be required to surrender unconditionally. The declaration stunned many observers, including some Allied officials, who worried it would stiffen enemy resistance. Roosevelt, however, believed clarity was essential. Unconditional surrender would eliminate ambiguity, prevent separate peace deals, and ensure that fascist regimes were dismantled entirely—not merely negotiated out of existence.

Churchill, though initially cautious, ultimately endorsed the policy, recognizing its psychological and political value. The announcement reassured Allied publics, signaled resolve to the Soviets, and framed the war as a moral struggle rather than a limited geopolitical contest. It also foreshadowed the postwar order the Allies intended to build—one in which the causes of global conflict would be uprooted, not accommodated.

Strategically, Casablanca produced a series of incremental but decisive decisions. The Allies agreed to complete the campaign in North Africa, invade Sicily, intensify bombing against Germany, and continue preparations for a future invasion of Western Europe. The conference confirmed that Allied strategy would be coordinated, sequential, and cumulative—applying pressure across multiple fronts to exhaust the Axis war machine.

Equally important was the symbolism of the meeting itself. Casablanca demonstrated that Allied leadership was becoming institutionalized rather than ad hoc. Roosevelt and Churchill were no longer merely reacting to events; they were shaping a coherent, long-term plan for victory. The conference helped establish the pattern of high-level Allied summits that would follow—Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam—each building on the precedent set in January 1943.

In retrospect, the Casablanca Conference marked the moment when Allied victory became a matter of execution rather than aspiration. The war would still demand immense sacrifice, and its end remained more than two years away. But on January 14, 1943, in a guarded enclave on the edge of the Atlantic, the Allies moved decisively from survival to strategy and laid the groundwork for the final, irreversible defeat of the Axis powers.