On January 29, 1886, a German engineer named Karl Benz quietly filed a patent that would help remake the modern world. The document, submitted to the Imperial Patent Office in Berlin, described a “vehicle powered by a gas engine.” It carried little fanfare at the time, but it marked the birth of the first successful gasoline-driven automobile—and the beginning of the transportation revolution that would reshape economies, cities, warfare, and daily life.

Benz’s invention, later known as the Benz Patent-Motorwagen, was a radical departure from the horse-drawn carriages that dominated 19th-century travel. Rather than adapting existing vehicles, Benz designed his machine from the ground up around a lightweight internal combustion engine. The result was a three-wheeled carriage powered by a single-cylinder, four-stroke gasoline engine capable of propelling itself without animal labor or external rails.

At the time, self-propelled vehicles were not an entirely new idea. Steam-powered road vehicles had existed for decades, but they were heavy, slow to start, mechanically complex, and often dangerous. Gasoline engines, still in their infancy, promised a lighter, more flexible alternative—but few inventors had succeeded in making them reliable enough for everyday use. Benz, trained as a mechanical engineer and hardened by years of financial struggle, succeeded where others failed by marrying simplicity with precision engineering.

The Patent-Motorwagen produced less than one horsepower and topped out at roughly ten miles per hour. By modern standards it was crude, noisy, and fragile. Yet it worked. It could be started, steered, and driven by a single operator over ordinary roads. In an age when most people rarely traveled farther than a day’s walk from home, the implications were enormous.

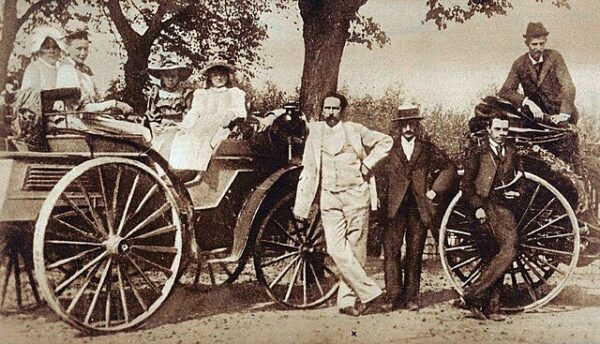

Public reaction, however, was skeptical. Early demonstrations were met with curiosity and occasional ridicule. The vehicle rattled, backfired, and emitted strange smells. Horses were spooked. Roads, designed for hooves and wagons, were poorly suited to mechanical travel. Even Benz himself struggled to convince investors and customers that the automobile had a future.

The turning point came not from Karl Benz, but from his wife, Bertha Benz. In August 1888, without informing her husband, she undertook the first long-distance automobile journey, driving the Motorwagen more than 60 miles from Mannheim to Pforzheim. Along the way, she solved mechanical problems, improvised fuel stops at pharmacies, and proved that the automobile was not merely a novelty, but a practical means of transportation. Her journey transformed public perception and secured Benz’s place in history.

By the 1890s, Benz’s company was producing vehicles commercially, and competitors across Europe and the United States rushed to develop their own designs. What followed was a cascade of change. Roads were paved. Cities expanded outward. Industries rose around steel, rubber, oil, and manufacturing. Entire regions reorganized themselves around the mobility the automobile provided.

The automobile also altered the rhythm of everyday life. It compressed distance, expanded labor markets, reshaped leisure, and accelerated the pace of commerce. In war, it transformed logistics and mechanized conflict. In peace, it redefined personal freedom and economic opportunity—while introducing new risks, from pollution to traffic fatalities, that societies are still grappling with today.

When Karl Benz filed his patent on January 29, 1886, he could not have foreseen all of these consequences. But his invention marked a decisive break from the limitations of muscle-powered transport. It was the moment motion itself became mechanical, personal, and scalable.

The modern world still runs on that idea.