On February 19, 1945, after days of relentless naval and aerial bombardment, approximately 30,000 United States Marines stormed the black volcanic beaches of Iwo Jima, a small, sulfur-scented island in the western Pacific that would become one of the bloodiest battlefields in American military history.

The assault marked the opening phase of the Battle of Iwo Jima, a five-week struggle between U.S. forces and entrenched troops of the Imperial Japanese Army. Though only eight square miles in size, Iwo Jima held enormous strategic value. Located roughly 750 miles south of Tokyo, the island sat midway between American air bases in the Mariana Islands and the Japanese home islands. U.S. planners believed capturing it would provide emergency landing fields for damaged B-29 bombers and a base for fighter escorts attacking Japan.

The invasion force fell under the command of Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith and Major General Harry Schmidt, with Marines from the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Divisions spearheading the landing. Offshore, hundreds of ships from the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard supported the operation, part of the broader Pacific “island-hopping” campaign aimed at closing in on Japan.

American leaders expected fierce resistance but believed preliminary bombardment had softened Japanese defenses. They were mistaken.

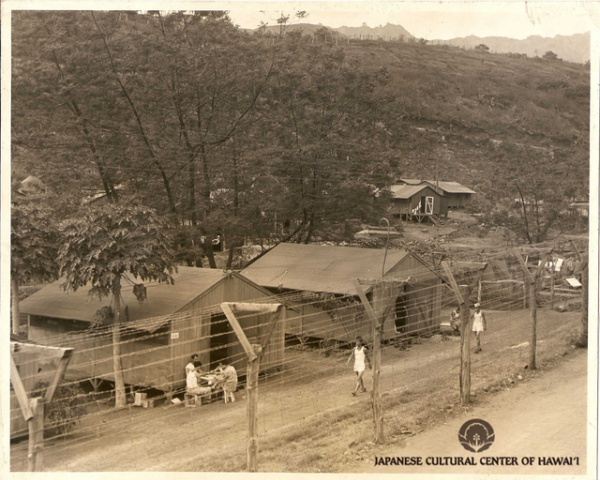

Waiting for them was a garrison of roughly 21,000 Japanese soldiers commanded by General Tadamichi Kuribayashi. Anticipating invasion, Kuribayashi had abandoned traditional beach defenses. Instead, he constructed an elaborate network of underground tunnels, bunkers, and hidden artillery positions carved deep into the island’s volcanic rock. His strategy was not to repel the Marines at the shoreline but to draw them inland and inflict maximum casualties.

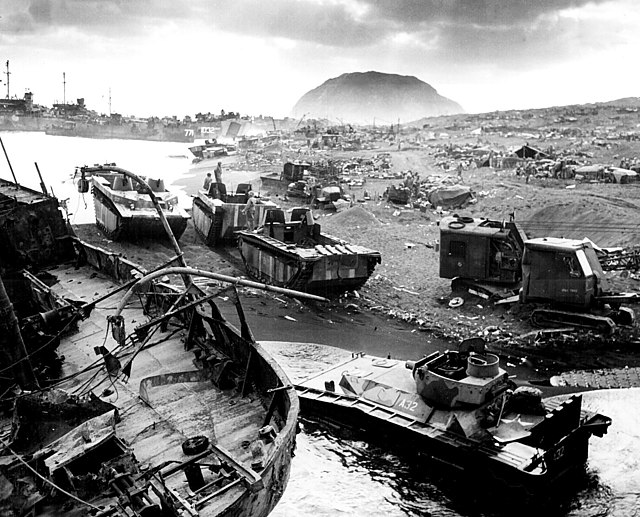

When the first wave hit the beaches shortly after 9 a.m., the Marines encountered an eerie quiet. The soft ash sand made movement difficult, bogging down men and machinery alike. Then, as landing zones filled with troops and equipment, Japanese artillery opened fire from concealed positions. Mortars and machine guns raked the beaches. Within hours, the shoreline became a chaotic scene of smoke, shattered vehicles, and mounting casualties.

One of the first objectives was Mount Suribachi, a 554-foot dormant volcano dominating the island’s southern tip. Securing it would remove a major observation post and artillery threat. Fighting up its steep slopes proved brutal, with Marines forced to clear cave after cave in close-quarters combat.

On February 23, after days of intense fighting, a patrol reached the summit of Suribachi and raised an American flag. Later that day, a second, larger flag was hoisted—an event captured in an iconic photograph by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal. The image of six Marines straining to lift the flagpole became one of the most enduring symbols of the war and was later immortalized in the Marine Corps War Memorial near Washington, D.C.

Yet the flag-raising marked not victory, but only the end of the battle’s opening phase.

For weeks, Marines fought yard by yard across the island’s northern ridges and ravines. Japanese defenders, operating from fortified positions connected by tunnels, emerged to launch sudden counterattacks before disappearing underground. Flamethrowers, grenades, and demolition charges became essential tools in clearing bunkers. Casualties mounted steadily.

By the time the island was declared secure on March 26, nearly 6,800 American service members had been killed and more than 19,000 wounded. Of the roughly 21,000 Japanese defenders, only a few hundred were captured alive; the vast majority were killed in action, many fighting to the last.

The battle’s strategic value was debated even before the war ended. Supporters argued that Iwo Jima provided a critical emergency landing site for hundreds of damaged B-29 bombers returning from raids over Japan, potentially saving thousands of American airmen. Critics later questioned whether the enormous human cost justified the gains.

What remains undisputed is the battle’s ferocity and symbolic power. Iwo Jima became synonymous with Marine Corps sacrifice and tenacity. It was one of the few Pacific battles in which American casualties exceeded those of the Japanese defenders, underscoring the intensity of the struggle.

Just seven months after the first Marines hit the beaches of Iwo Jima, Japan would surrender following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But on that February morning in 1945, as 30,000 Marines advanced into black sand under a storm of fire, the war’s end was far from certain, and the cost of reaching it would be measured in blood and ash.