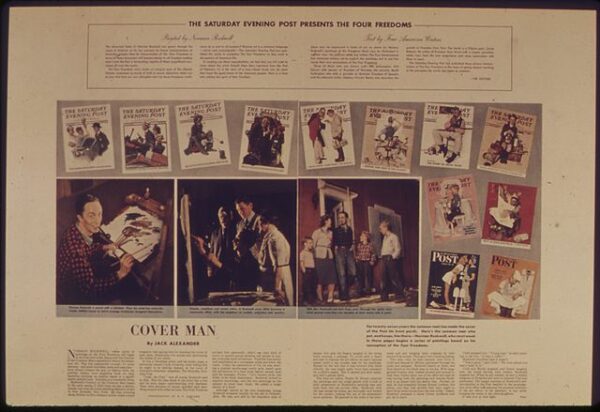

On February 20, 1943, The Saturday Evening Post published the first installment of what would become one of the most recognizable artistic statements of the Second World War: Norman Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms.” Inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union address, the series translated lofty wartime rhetoric into intimate scenes of American life. At a moment when the United States was deeply entrenched in global conflict, Rockwell’s paintings offered a visual reminder of what, precisely, the nation believed it was fighting to preserve.

Roosevelt had delivered his Four Freedoms address on January 6, 1941, nearly a year before Pearl Harbor drew the country formally into the war. In that speech, he identified four essential human liberties that ought to be secured everywhere in the world: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. These were not presented as narrow constitutional guarantees but as universal aspirations—moral touchstones in an era of totalitarian expansion.

By early 1943, those words had acquired renewed urgency. American troops were engaged in North Africa and the Pacific, and the home front was defined by rationing, war production, and casualty reports. Into this atmosphere stepped Rockwell, a celebrated illustrator whose covers for The Saturday Evening Post had already made him a household name. Rather than depict battlefield heroics or allegorical figures, Rockwell chose a more restrained and, in many ways, more radical approach: he embedded Roosevelt’s sweeping ideals in the everyday rituals of small-town America.

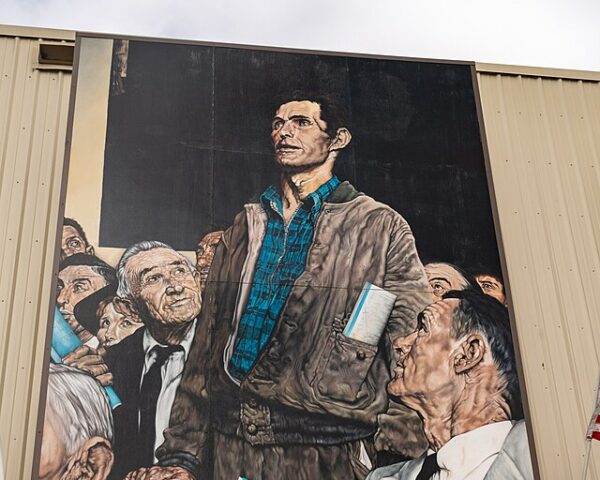

The first painting to appear in the Post on February 20 was “Freedom of Speech.” It portrayed a working-class man standing in a town meeting, speaking candidly while his neighbors—dressed more formally—listened with attentive respect. The composition emphasized dignity and civic equality. The speaker’s rough jacket and weathered hands stood in quiet contrast to the polished attire around him, yet he commanded the room. In Rockwell’s framing, democratic participation itself became a heroic act.

In the weeks that followed, the Post published the remaining three paintings. “Freedom of Worship” showed men and women of varied faith traditions in solemn prayer, their expressions serene and introspective. “Freedom from Want” depicted a multigenerational family gathered around a Thanksgiving table, the matriarch presenting a roast turkey as relatives looked on with anticipation. “Freedom from Fear” captured a quieter domestic scene: parents tucking their children into bed while headlines about bombings and war rested in the father’s hands.

The imagery was deliberate. In 1943, Americans were living under ration books and blackout drills. The Thanksgiving table in “Freedom from Want” appeared at a time when many staples were scarce. The bedtime scene in “Freedom from Fear” resonated with families whose sons were overseas. Rockwell did not deny the strains of war; instead, he suggested that these intimate moments—speech in a town hall, prayer in quiet devotion, family gathered at table, children sleeping in safety—were precisely what the conflict sought to protect.

The response was immediate. Readers flooded the magazine with requests for reproductions. The U.S. Treasury Department quickly enlisted the paintings in a nationwide war bond campaign. The original works toured the country, drawing millions of visitors and helping to raise more than $130 million in bond sales. In practical terms, the series became a powerful instrument of wartime mobilization, reinforcing morale while generating tangible financial support for the war effort.