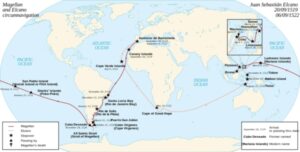

On September 20, 1519, Ferdinand Magellan set sail from Spain in an effort to find a western sea route to the Spice Islands, looking to change the ocean-going world. This epic journey, which began in 1519 and concluded in 1522, marked the first successful attempt to sail around the world.

In command of five ships, Magellan, a Portuguese explorer sailing under the flag of Spain, “sailed to West Africa and then to Brazil, where he searched the South American coast for a strait that would take him to the Pacific. He searched the Rio de la Plata, a large estuary south of Brazil, for a way through; failing, he continued south along the coast of Patagonia. At the end of March 1520, the expedition set up winter quarters at Port St. Julian. On Easter day at midnight, the Spanish captains mutinied against their Portuguese captain, but Magellan crushed the revolt, executing one of the captains and leaving another ashore when his ship left St. Julian in August, writes The History Channel.

“On October 21, he finally discovered the strait he had been seeking. The Strait of Magellan, as it became known, is located near the tip of South America, separating Tierra del Fuego and the continental mainland. Only three ships entered the passage; one had been wrecked and another deserted. It took 38 days to navigate the treacherous strait, and when ocean was sighted at the other end Magellan wept with joy. He was the first European explorer to reach the Pacific Ocean from the Atlantic. His fleet accomplished the westward crossing of the ocean in 99 days, crossing waters so strangely calm that the ocean was named “Pacific,” from the Latin word pacificus, meaning “tranquil.”

The expedition’s most significant achievement came when one of Magellan’s remaining ships, the Victoria, under the command of Juan Sebastián Elcano, completed the circumnavigation by returning to Spain in 1522. Only 18 crew members, out of the original hundreds, survived the grueling journey. This successful circumnavigation demonstrated that the Earth was indeed round and provided invaluable knowledge about the world’s vastness and interconnectedness.

Historian Antonio Feros, who specializes in the history of early modern Spain, said during a celebration of the 500th anniversary of the trek that Magellan’s “voyage definitively demonstrated that the globe was round, and in reflecting about this voyage, some geographers started to better understand the globe, the various regions of the world. The ‘Universal Map’ drawn by Diogo Ribero in 1529 is clear proof of this.

But these were the unintended consequences of Magellan’s voyage. His was not a scientific expedition, it was a commercial and political expedition, an intent by the Spanish monarchy to enter into the wealthy Asian trade, dominated until then by the Portuguese. Magellan was a sailor, a man serving a king, not a geographer or a scholar. He wanted to discover a route that gave the Spanish monarchy economic power and political influence, but he was not interested in the advancement of geography, or science. He never wrote any treatise about the geography, or the world—mapmakers did that. He was thinking and acting as a man of state.

The real consequences of his voyage were economic and commercial: It allowed the Spanish to establish commercial routes between its colonies in the Americas and the territories they ended controlling in Asia—like the commercial route between the Philippines and Acapulco in Mexico, ‘the Manila Galleons,’ which lasted for more than two centuries. It also accelerated the connections between the various regions of the world.

By the mid-1500s, as a consequence of Magellan’s voyage and many others after him, Europeans became aware that Spanish and Portuguese explorations had ushered in the first period of globalization in the history of humanity. As the French writer Louis Le Roy wrote in 1577, thanks to these voyages and expeditions ‘all humans can now exchange commodities with one another and provide for each other’s dearth, like residents of one city and one republic of the world.’”