During the winter of 1775-1776, General George Washington faced a dire need for artillery to break the British siege of Boston. That’s when Brigadier General Henry Knox, Washington’s Chief of Artillery, proposed a daring plan to transported “the guns of Ticonderoga” to Beantown, covering nearly 300 miles of treacherous terrain in what’s considered one of the greatest logistical feats in American military history.

The expedition began on December 5, 1775, when Knox led a group of men to retrieve the artillery pieces from Fort Ticonderoga. The harsh winter conditions made the journey perilous, with the men facing freezing temperatures, rough terrain, and the challenges of crossing frozen rivers. Remarkably, Knox successfully transported 59 cannons and mortars, including heavy siege guns, across snow-covered landscapes and icy waterways.

Knox had been a bookseller before the outbreak of war, and his bookshop was known as “a fashionable morning lounge” that counted John Adams among its regular patrons. After Lexington and Concord, Knox and his wife snuck out of Boston in disguise. With a commission as a colonel in the Continental Army, Knox went to Washington and confidently predicted that once the cannons had been taken by boat from Fort Ticonderoga to the southern end of Lake George, it would take fewer than twenty days to move them overland to Boston, writes The Battlefield Trust.

Henry Knox left for Fort Ticonderoga on November 16, 1775. Once he arrived at the fort, he selected 58 pieces of artillery to take back to Boston. Most of artillery pieces were “12-pounder” or “18-pounder” cannons (depending on the weight of the cannonball they fired). Knox also brought one massive 24-pounder cannon, nicknamed “Old Sow,” that weighed more than 5,000 pounds and several high-arching mortar guns that weighed one ton each. In total, Henry Knox’s “noble train of artillery” weighed 120,000 pounds, or 60 tons.

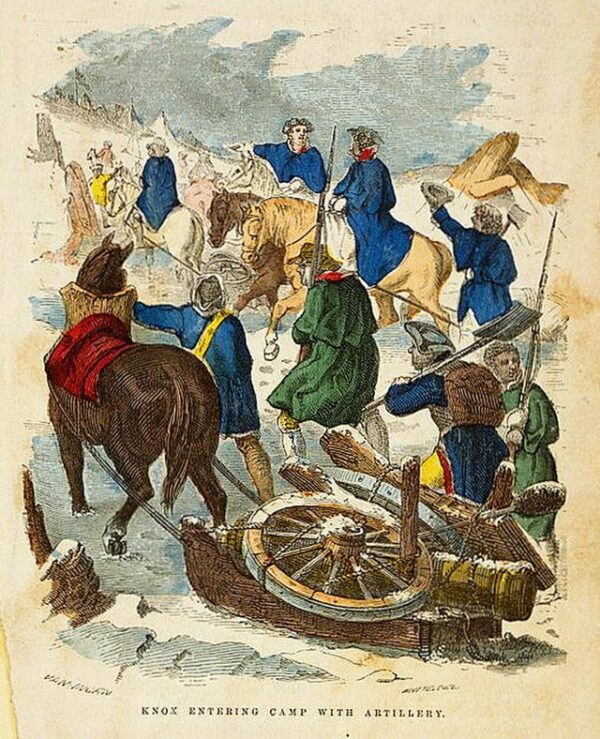

On December 9, 1775, three boats loaded with artillery set sail on Lake George. Traveling forty miles down the ice-covered lake took eight days. Once the artillery was on the southern shore of the lake, Knox and his men used more than one-half mile of rope to secure the guns to 42 sleds. Hauling the heaviest guns required eight horses and sometimes additional oxen as well.

The journey on land required crossing the frozen Hudson River four times. The leader of each sled team carried an axe, so that if a cannon fell through the ice they could cut the lines before it dragged the horses underwater as well. Henry Knox himself nearly froze to death while trying to walk through three feet of snow in a blizzard. In a letter to Washington, he wrote that “it is not easy to conceive the difficulties we have had,” but not a single cannon was lost. Henry Knox and his noble train of artillery arrived at the Continental Army camp outside Boston in late January 1776. The journey that Knox had estimated would take sixteen or seventeen days had taken forty.

The captured artillery proved instrumental in forcing the British to evacuate Boston in March 1776. This accomplishment showcased the determination and resilience of the American forces, proving that they could overcome significant challenges to secure the tools necessary for victory.

The Noble Train of Artillery became a symbol of ingenuity and determination in the face of adversity. It exemplified the Continental Army’s ability to adapt and innovate, using unconventional methods to achieve strategic objectives. The success of this expedition not only boosted the morale of the American forces but also demonstrated the leadership and strategic thinking of figures like General Washington and General Knox.

Most importantly, it freed Boston.