In 1933, during the throes of the Great Depression, the United States found itself grappling with severe economic turmoil. In an unprecedented move to stabilize the economy and bolster confidence in the financial system, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6102 on April 5, 1933. This executive order, commonly referred to as the Gold Confiscation Order, effectively prohibited the private ownership of gold coins, gold bullion, and gold certificates by American citizens.

The decision to seize gold was driven by a combination of factors. The nation was in the midst of a banking crisis, with widespread bank runs and a collapsing financial system. The gold standard, which pegged the value of the dollar to a fixed amount of gold, constrained the government’s ability to enact monetary policies to combat deflation and stimulate economic growth. Additionally, the Treasury’s gold reserves were dwindling, and there were concerns about a potential gold drain as people hoarded gold amidst economic uncertainty.

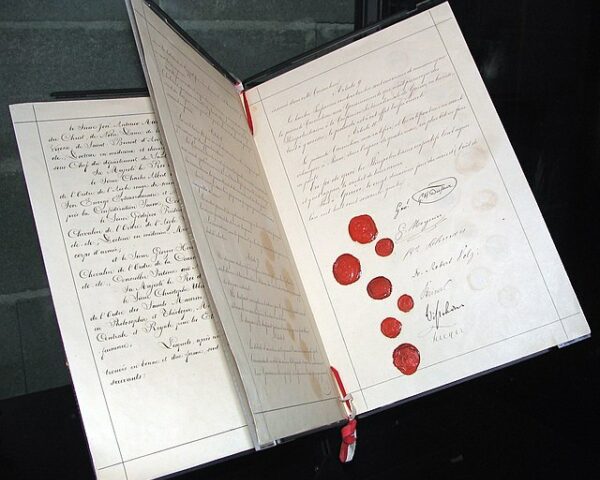

Under Executive Order 6102, citizens were required to deliver all gold coins, gold bullion, and gold certificates to the Federal Reserve by May 1, 1933. The order made exceptions for certain uses, such as jewelry and collector’s coins, as well as for industrial and artistic purposes. However, individuals were required to declare such holdings and obtain special licenses.

The repercussions of Roosevelt’s decision were profound. Many Americans felt their property rights were violated, and there was widespread public outcry against the government’s actions. Critics argued that the gold seizure was an unconstitutional overreach of executive power and a violation of individual liberties. Legal challenges to the order ensued, but the Supreme Court ultimately upheld its constitutionality in the landmark case of Gold Clause Cases in 1935.

Despite the controversy, the gold confiscation had significant implications for the U.S. economy. By removing gold from circulation and effectively devaluing the dollar, Roosevelt sought to stimulate inflation and encourage spending to combat the deflationary pressures of the Great Depression. The government then set the price of gold at $20.67 per ounce, effectively devaluing the dollar against gold.

The devaluation of the dollar had mixed results. On the one hand, it helped stabilize the banking system by boosting confidence in the government’s ability to manage the economy. It also provided a much-needed injection of liquidity into the financial system, which helped alleviate some of the acute liquidity shortages that were crippling banks and businesses. Additionally, the devaluation made American goods cheaper for foreign buyers, which helped stimulate exports and create jobs in industries such as manufacturing and agriculture.

However, the devaluation also had negative consequences. It eroded the purchasing power of savings and pensions denominated in dollars, causing hardship for savers and retirees. Moreover, it sparked concerns about the stability of the dollar and the government’s commitment to sound monetary policy. These concerns were exacerbated by subsequent devaluations and the eventual abandonment of the gold standard by the United States in 1971.