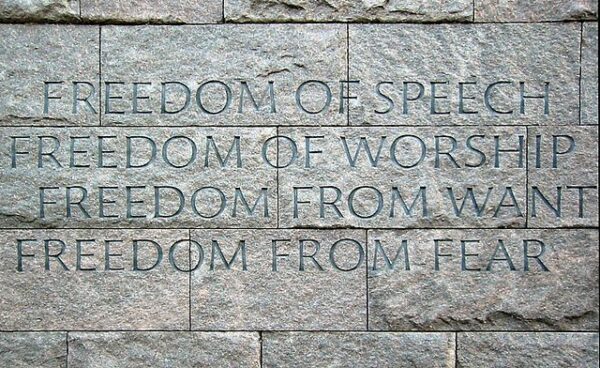

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, granting the military broad authority to exclude individuals from designated areas. Though the order did not explicitly mention Japanese Americans, it became the legal basis for one of the most severe violations of civil liberties in U.S. history—the forced relocation and internment of around 120,000 people of Japanese descent, two-thirds of whom were American citizens.

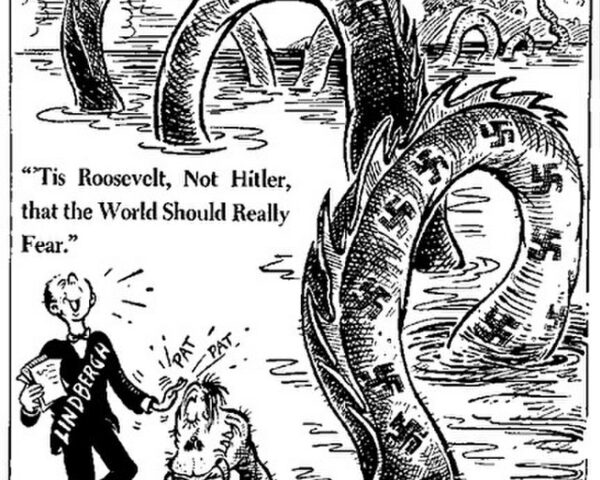

This policy emerged from a combination of wartime fear, racial prejudice, and deep-seated anti-Japanese sentiment. Long before the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Japanese Americans faced discrimination, particularly on the West Coast, where restrictive laws and segregationist policies limited their economic and social opportunities. After the U.S. entered World War II, suspicion and hostility escalated. Many government officials, military leaders, and citizens feared that Japanese Americans might serve as spies or saboteurs for Japan, despite a lack of evidence.

Public figures like California Attorney General Earl Warren advocated for preemptive action, claiming that national security required drastic measures. General John L. DeWitt, who oversaw the Western Defense Command, reinforced the belief that ancestry, rather than individual behavior, determined loyalty. Despite opposition from figures such as FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover—who found no credible evidence of espionage—Executive Order 9066 led to the removal of Japanese Americans from their homes and communities, particularly along the West Coast.

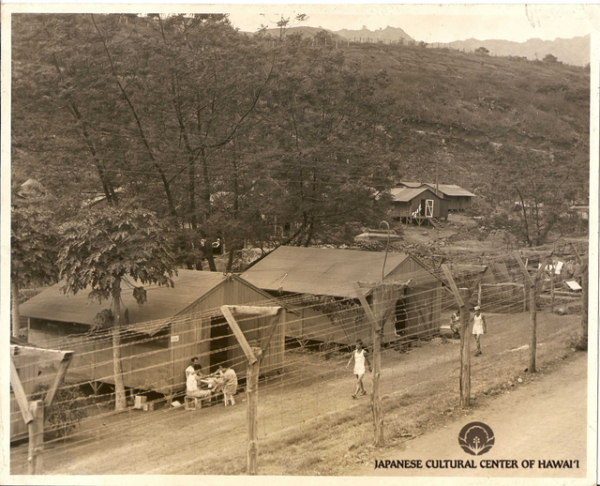

Families were forced to leave behind businesses, homes, and possessions, often selling their property at unfairly low prices. Initially detained at makeshift assembly centers, including racetracks and fairgrounds, they were later sent to ten internment camps in remote locations, such as Manzanar in California and Minidoka in Idaho. These camps, surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by armed soldiers, subjected internees to harsh living conditions, extreme weather, and inadequate facilities.

At the time, opposition to internment was minimal. Although some civil rights groups and religious organizations protested, wartime propaganda and racial anxieties led much of the public to accept the policy. The Supreme Court upheld the government’s actions in Korematsu v. United States, ruling that national security justified the internment. It was not until decades later that this decision was formally criticized. In 1983, a federal court overturned Fred Korematsu’s conviction, and in 1988, the U.S. government issued a formal apology and financial reparations to surviving internees through the Civil Liberties Act.