On December 7, 1941, the United States was thrust into global war when aircraft of the Imperial Japanese Navy launched a sudden and meticulously coordinated attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The assault began early on a quiet Sunday morning, catching American forces completely by surprise. Japanese warplanes struck battleships anchored along Battleship Row and targeted nearby airfields to prevent any American counterattack. Four U.S. battleships were destroyed or sunk, several others were damaged, dozens of additional ships were impaired, and close to 200 aircraft were burned or blasted on the ground. More than 2,400 Americans were killed and more than 1,200 were wounded. The scale of the strike, combined with its strategic precision and secrecy, shocked the nation.

News of the attack reached Washington while President Franklin D. Roosevelt was at the White House preparing for the week ahead. Initial messages from naval officers in Hawaii were brief and alarming, indicating that explosions were occurring throughout the harbor and that enemy aircraft were overhead. Roosevelt immediately convened emergency meetings with senior military advisers, intelligence officials, and congressional leaders. Throughout the day, as casualty and damage assessments accumulated, it became clear that the attack represented a deliberate act of war that could not be dismissed, contained, or delayed.

The shock of the attack cut through lingering isolationist sentiment that had dominated much of American political discourse throughout the 1930s. For years, many Americans had believed that staying out of both the European war and Asian conflict was the safest and wisest course. That belief evaporated in the hours after the attack. The strike was interpreted not merely as a military maneuver but as a direct assault on American sovereignty, requiring an unambiguous national response.

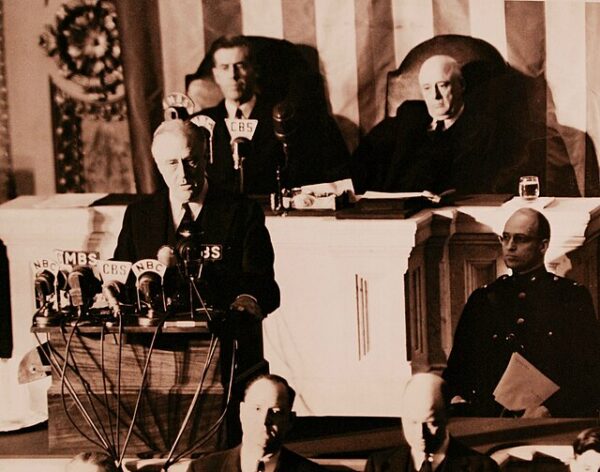

On the morning of December 8, Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress in a speech that instantly became one of the most recognizable in American history. He began with a stark and memorable phrase: “Yesterday, December 7, 1941, a date which will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.” Roosevelt then recounted the scale of the destruction, emphasized the gravity of the loss of life, and noted that Japanese envoys in Washington had been discussing peace terms even as the attack had been secretly planned. He catalogued additional Japanese offensive actions across the Pacific, including invasions and bombardments in the Philippines, Guam, and elsewhere, demonstrating that the attack on Pearl Harbor was part of a wider coordinated military campaign.

Roosevelt’s speech lasted only a few minutes but achieved its objective with overwhelming clarity: to prepare Congress and the American public for the necessity of war. The president declared that the United States would respond decisively and win ultimate victory. The galleries erupted in applause as the speech concluded.

Immediately afterward, Roosevelt asked Congress for a declaration of war against the Empire of Japan. The Senate voted unanimously in favor. The House overwhelmingly agreed, with only one dissenting vote, cast by Representative Jeannette Rankin of Montana, a lifelong pacifist who had also opposed American entry into World War I. Within hours, Roosevelt signed the resolution, and the United States formally entered World War II.

The declaration transformed the strategic balance of the conflict. American mobilization began at once. Factories shifted to war production, young men lined up at recruiting stations, and communities across the country unified behind the war effort. Within days, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, broadening the conflict and committing the nation to a truly global struggle.

The phrase “a date which will live in infamy” has endured for generations, symbolizing not only the surprise and tragedy of the attack but also the moment when the United States shed its reluctance and embraced its role as a decisive combatant in World War II.