On February 9, 1942, the United States did something that would have seemed mildly absurd just a few years earlier: it reset the nation’s clocks—permanently, at least for the duration of the war. With the country barely two months removed from Pearl Harbor, Congress and the Roosevelt administration reinstated year-round daylight saving time, officially rechristened “War Time,” as part of a broader effort to conserve energy and discipline civilian life for total war.

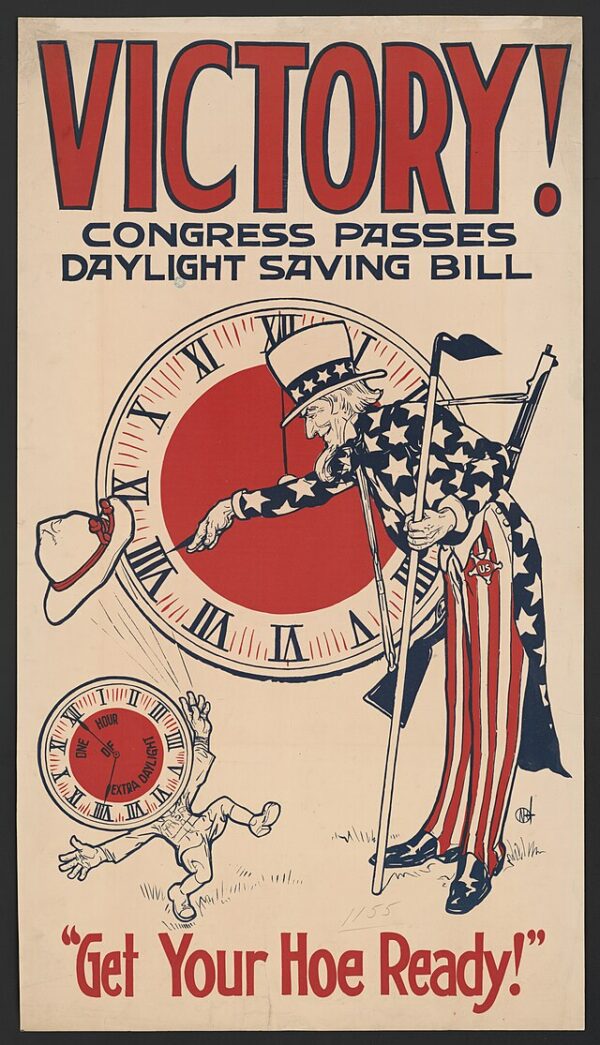

The logic was simple, if not universally beloved. By pushing clocks one hour ahead year-round, Americans would make greater use of daylight in the evening, reducing the demand for artificial lighting and electricity at a moment when coal, oil, and power generation were being diverted toward factories, shipyards, and military installations. The measure echoed a similar experiment during World War I, when daylight saving time had first been adopted nationally in 1918, only to be repealed soon after the armistice.

In 1942, however, the stakes were higher—and the tone far more serious. The United States was mobilizing on a scale never before attempted. Industrial output was exploding, cities were dimming streetlights to guard against potential air raids, and ordinary Americans were being told—sometimes politely, sometimes bluntly—that comfort was a luxury the nation could no longer afford. “War Time” fit neatly into a culture of ration books, scrap drives, victory gardens, and exhortations to “do your part.”

The federal mandate, signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, took effect nationwide at 2:00 a.m. on February 9. For the first time, all clocks in the continental United States ran on daylight saving time continuously, eliminating the seasonal shift back to standard time in the fall. The country would remain on War Time until September 1945, several weeks after Japan’s formal surrender.

Supporters framed the policy as both practical and patriotic. Longer daylight hours in the evening, they argued, reduced household energy use and improved morale by giving workers a sliver of sunlight after long factory shifts. Defense plants running around the clock could better coordinate shift changes. Retailers benefited from brighter shopping hours, and transit systems found scheduling marginally simpler without seasonal clock changes.

But War Time also disrupted daily life in ways that fell unevenly across the country. In northern states, winter mornings became profoundly dark. Schoolchildren waited for buses before sunrise; farmers complained that the clock no longer matched the rhythms of livestock or crops. In some rural areas, resistance was quiet but persistent, with communities informally keeping “sun time” despite the law.

Still, open opposition remained limited during the war years. With hundreds of thousands of Americans dying overseas, arguing about sunrise felt faintly unseemly. Newspapers generally treated War Time as an inconvenience worth enduring, another reminder that civilian routines were now subordinate to military necessity. Even critics tended to frame their objections in practical terms rather than ideological ones.

The end of the war, however, reopened the debate almost immediately. Once the emergency passed, the rationale for year-round daylight saving time weakened, and public patience evaporated. In September 1945, the federal mandate expired, returning the country to a confusing patchwork of local time observances. Some cities kept daylight saving time; others abandoned it. The result—later dubbed the era of “chaos time”—persisted until Congress imposed new national standards in 1966.