In 1721, Johann Sebastian Bach presented a compiled collection of six concertos to Christian Ludwig, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt. He called them “Six Concerts à plusieurs instruments (Six Concertos for several instruments).

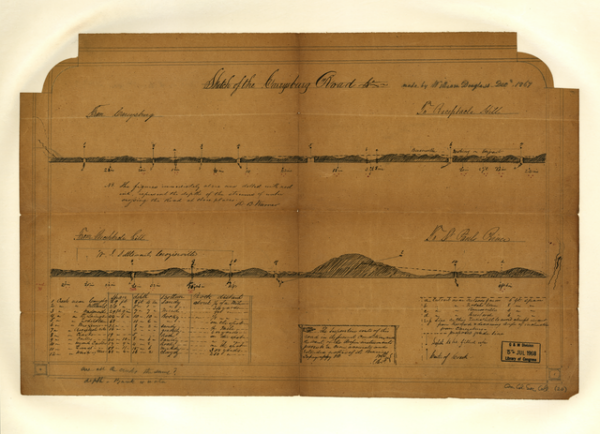

The works were so important to Bach that he wrote out the music himself rather than hire someone to copy it for him, as was often the custom in the 18th century.

Date March 24, Bach’s dedication to the Margrave read:

“As I had the good fortune a few years ago to be heard by Your Royal Highness, at Your Highness’s commands, and as I noticed then that Your Highness took some pleasure in the little talents which Heaven has given me for Music, and as in taking Leave of Your Royal Highness, Your Highness deigned to honour me with the command to send Your Highness some pieces of my Composition: I have in accordance with Your Highness’s most gracious orders taken the liberty of rendering my most humble duty to Your Royal Highness with the present Concertos, which I have adapted to several instruments; begging Your Highness most humbly not to judge their imperfection with the rigour of that discriminating and sensitive taste, which everyone knows Him to have for musical works, but rather to take into benign Consideration the profound respect and the most humble obedience which I thus attempt to show Him.”

“Johan Sebastian Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos are classical music standouts for numerous reasons. This collection of six concertos nearly fell victim to becoming lost history, as have so many of Bach’s works. Yet today they’re considered the virtuoso collection of the variety and apex of Baroque music,” according to Connolly Music.

“Each concerto is a concerto grosso, a concerto that’s a continuous interplay of small groups of soloists and full orchestra. Bach, himself, titled the compilation of concertos simply “Concerts avec plusieurs instruments” (concerts for several instruments). Indeed, the range of instruments with solos throughout the six concertos was designed to give opportunities to show the potential of nearly every instrument in the orchestra. Even the recorder got a solo. The recorder.

Each concerto itself presents a different example of Baroque music, sort of a Baroque musical travelogue moving through “the courtly elegance of the French suite, the exuberance of the Italian solo concerto and the gravity of German counterpoint.”

One site has noted that “in the modern era these works have been performed by orchestras with the string parts each played by a number of players, under the batons of, for example, Karl Richter and Herbert von Karajan. They have also been performed as chamber music, with one instrument per part, especially by (but not limited to) groups using baroque instruments and (sometimes more, sometimes less) historically-informed techniques and practice. There is also an arrangement for four-hand piano duet by composer Max Reger.

The first two bars of the sixth concerto’s third movement (transposed in C major) are often used as a lead-in for radio programs distributed by American Public Media.”