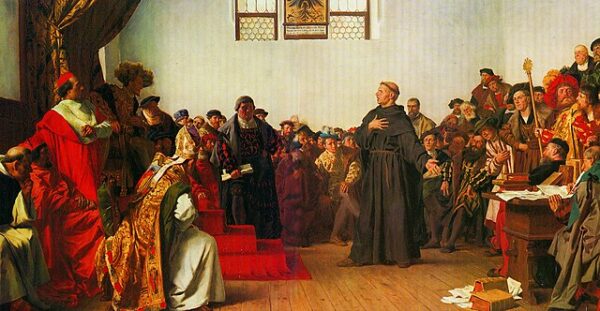

The Diet of Worms, convened in 1521, stands as a pivotal moment in the history of the Reformation and European religious politics. This imperial council, held in the German city of Worms, was summoned by Emperor Charles V to address the burgeoning theological controversy stirred by Martin Luther. Luther, a German monk and professor of theology, had ignited a religious revolution with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517, which criticized the Catholic Church’s sale of indulgences and other practices. The Diet of Worms aimed to resolve the escalating conflict between Luther and the Roman Catholic Church, which threatened the unity of Christendom.

The proceedings began on January 28, 1521, with representatives from various German states, the papal nuncio, and other key ecclesiastical and secular figures in attendance. The central issue was Luther’s alleged heresy, encapsulated in his writings, which included “On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church” and “On the Freedom of a Christian.” These works challenged the authority of the Pope, the efficacy of sacraments administered by corrupt clergy, and other core tenets of Catholic doctrine.

Luther was summoned to appear before the Diet to recant his teachings. On April 16, 1521, he made his initial appearance. Over the next several days, the tension mounted as Luther was pressed to renounce his views. His famous response on April 18 encapsulated the crux of the Reformation: “Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. May God help me. Amen.”

Luther’s refusal to recant was a bold assertion of individual conscience and scriptural authority over institutional orthodoxy. His stance symbolized the growing rift between reformers and the Catholic establishment. Recognizing the threat Luther posed, as well as the potential political repercussions of his execution, Emperor Charles V issued the Edict of Worms on May 25, 1521. This edict declared Luther an outlaw, banned his literature, and mandated his arrest. It also prohibited anyone from providing him food or shelter, effectively making him a fugitive.

Despite the edict, Luther was clandestinely protected by Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, who had Luther taken to Wartburg Castle for his safety. During his stay at Wartburg, Luther translated the New Testament into German, further spreading his reformist ideas among the German-speaking populace and making the scriptures more accessible to the laity.

The Diet of Worms and its conclusion marked a significant escalation in the Reformation. It unequivocally demonstrated that the theological disputes sparked by Luther could not be contained within academic debate or ecclesiastical courts. Instead, these issues had broad social, political, and cultural ramifications. The Edict of Worms failed to suppress Luther’s influence; rather, it galvanized his supporters and intensified calls for reform across Europe.

In essence, the Diet of Worms set the stage for the Protestant Reformation, a movement that would profoundly reshape Christianity and Western civilization. It underscored the limitations of imperial and papal authority in the face of burgeoning demands for religious and intellectual freedom.

Luther’s defiance and the subsequent political maneuverings highlighted the complex interplay between faith, power, and conscience, setting a precedent for future conflicts and reforms. The events at Worms in 1521 thus remain a defining moment in the history of the Reformation, emblematic of the enduring struggle for religious liberty and the assertion of personal conviction against institutional authority.